french artist Laurent Grasso (b. 1972) has a practice centered on the immaterial and often scientific facets of existence – ranging from weather to electromagnetic energy – and the myriad possible ways in which these phenomena can be translated through artistic means into something corporeal . Drawing inspiration from film, art history, and international cultures, Grasso’s signature point of view is perpetually in motion and shifting, lending to works that invite the viewer to reconsider their own perceptions and perspectives.

Grasso’s multidisciplinary practice has been the subject of dozens of solo exhibitions worldwide, including her current solo exhibition “time is gone” at Tao Arts, Taipei, which runs until July 15, 2023.

We recently reached out to Grasso to find out more about the show and the motivations behind and the processes used in her work.

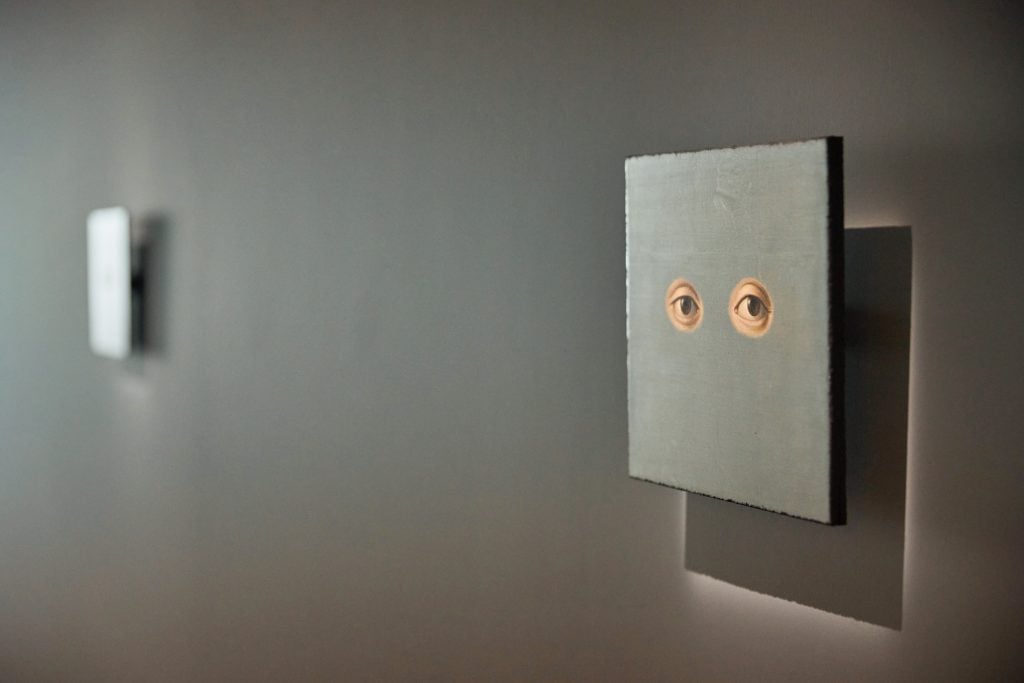

Installation view of “Laurent Grasso: Time goes away” (2023). Photo: Anpis Foto. Courtesy of Tao Art, Taipei, and Sean Kelly, New York.

Your solo exhibition “Time Leaves” started at Tao Arts, Taipei this month. Can you tell us a bit about the theme(s) of the show and the type of works included?

“Time Leaves” is a contraction of the notions that make up my exhibition, including, among others, the notion of time, time travel and leaves. These leaves can be interpreted both as overlapping layers of time and as a reference to the silver leaves used as a background in some of my paintings. There is of course the vegetal aspect which, associated with time, refers to a more dreamy, growing dimension.

My exhibition also focuses on the invisible and the immaterial. The three exhibition halls are immersed in a mysterious atmosphere. The walls have been painted in a very evanescent blue; the lighting is quite dim. The silver backgrounds of some paintings show the reflection of the film and the neon lights that are presented. As often, I try to create a climate and an atmosphere where the works vibrate and radiate. There is a play of reflections that creates a back and forth between the works.

In the first room, we see eyes on silver backgrounds. These eyes belong to masterpieces of art history. Neon creates a spectral and disturbing atmosphere. They evoke the eyes of surveillance and diffuse power of which Michel Foucault speaks, but also the vision that Derrida had of specters, in particular when he said: “I believe that cinema, when it is not boring, is art of bringing back ghosts. .”

In the second room, I present my film Otto created for the 21st Biennale of Sydney accompanied by a triptych combining spheres visible in the film with a setting inspired by a 17th century engraving by Kirchner, produced on a silver background.

In the third room, a mutant flower with a double heart evokes a new species of flower from the future, it is my Future Herbarium series.

Installation view of “Laurent Grasso: Time goes away” (2023). Photo: Anpis Foto. Courtesy of Tao Art, Taipei, and Sean Kelly, New York.

What kind of viewing experience do you hope the show’s visitors will have? Is there a key takeaway that you’ve been aiming for?

I try to interweave multiple forces, stories and ideas into a single object. For me, the exhibition is the work. I like that you don’t suddenly understand and that your state of consciousness can be modified, distorted. The film, the installation in space, as well as the sound and the lighting, allow a kind of alternative consciousness. I try to amplify this state and what will happen there.

Your work is materially very diverse, ranging from film to installation, including painting and sculpture. What does your creative process look like, where do you start? Would you describe it as more intuitive or more strategic?

I start from a theoretical point of view while incorporating a visual, conceptual and historical point of view, so that all my concerns are brought together in a work. Research is very important to my practice.

I have a pronounced taste for certain real or theoretical territories where our point of view on the world will be challenged, will waver. I also look for places with great strength, either by the beliefs that are invested there, or by their political dimension.

For my movie Otto, shown in the exhibition, I chose almost inaccessible sacred places, never filmed, and several hours away from the first city. I had to enter into diplomatic relations with an indigenous community. My idea was to film sacred sites with scientific tools and thus bring together opposite poles: thermal and hyper-spectral cameras with ancestral lands that are the subject of beliefs to which we do not have access because the aboriginal rites are secret . The customary owners gave me their agreement to film these sites. They were interested in making the world aware of their cause.

Generally, my work begins with the creation of a film which requires a lot of research. Each project is like a new chapter that I try to write. At the same time, objects appear, with different mediums, evoking different eras. They give the impression of having crossed the screen to exist in the exhibition space and create a feeling of deja vu.

Installation view of “Laurent Grasso: Time goes away” (2023). Photo: Anpis Foto. Courtesy of Tao Art, Taipei, and Sean Kelly, New York.

Can you tell us about the use of silver ink in several of your works?

Much of my work is rooted in research, collaborations with scientists. But I also like to find simple ways to create a certain magic and to make the works active and alive, through a strange feeling that they embody.

I like the idea of a magical action, of creating an interaction with the spectator, conscious or unconscious, something sensory. So in this respect I continue to use fairly simple but very evocative techniques like neon installations and reflective silver surfaces.

The silver background is a way for me to create the look of an image from a point of view. Depending on the viewer’s position, the image will be visible or invisible. The environment merges with the work through the reflection it arouses. This reflection evokes for me the speed of light and the fact that what appears to our eyes already belongs to the past.

Series like “Studies into the Past” started over a decade ago and are still ongoing. Do you expect these to ever end? Why or why not?

The “Studies of the Past” project is a time travel project. The idea is to play with the story and create an ambiguous object, so that the painting cannot be immediately dated. Some elements of my current work appear in historical compositions and feel like references on which my work could have been based. This series is quite dizzying and fascinating in its conception and realization. I really like the idea of putting works from a certain period in front of other much more futuristic works, and thus of opposing different temporalities.

Installation view of “Laurent Grasso: Time goes away” (2023). Photo: Anpis Foto. Courtesy of Tao Art, Taipei, and Sean Kelly, New York.

What is the place of art history in your work? Are there any specific artists, movements or periods that influenced or inspired you the most?

I am interested in a variety of different subjects. There is a very beautiful text by Amelia Barikin* in my catalog Dual Sun which deals with the relationship that exists in my work between art history and quantum entanglement. For me, it’s not a question of making a referenced work, but rather of creating the conditions for a journey through time, a fiction that often relies on scientific elements to reinforce a form of belief in the story that I propose. It’s even more plausible when it comes to things that are theoretically possible.

* “Quantum entanglements and the construction of time: do we need a science-fictional history of art?”, Dual Sunp. 17-24 (Dilecta, 2015).

What are you currently working on? Is there anything you hope to address next?

Following my project at Tao Art, I want to continue my experience in Taiwan and organize a shoot for my next film. This new film will feature a rectangle moving on landscapes totally untouched by human intervention. This rectangle would be an imaginary shape, with a power of action, which would not be obvious to the viewer.

Ideally, I would like to be able to organize this shoot fairly quickly and thus prolong my Taiwanese experience.

Installation view of “Laurent Grasso: Time goes away” (2023). Photo: Anpis Foto. Courtesy of Tao Art, Taipei, and Sean Kelly, New York.

“time is goneis on view at Tao Art, Taipei, through July 15, 2023.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.