Artists and designers today have an assortment of colors at their fingertips, but access to dyes hasn’t always been so easy. Their acquisition and production were fraught with difficulties, from battling alligators in logwood mangroves to punishing the loss of limb in 13th-century Italy for using “knockoff” scarlet. “. A new book by artist and designer Lauren MacDonald, In pursuit of color, brings together the history and origins of some of the world’s most important dyes. In neatly divided sections – alliteratively titled Flora, Fauna, Fungi and Fossil Fuels – MacDonald takes readers on a tour of the origins, myths and developments of different dyes, from the crushing of carnivorous sea snails to the synthesis of ‘alizarin. In the edited snippets below, we bring you some of the colorful stories behind the dyes.

The Bayer alizarin factory in 1961 Courtesy of Bayer AG, Bayer Archives Leverkusen

Putrid purple of Pliny: murex

The origin story of purple murex dye has become a myth. One day, the Phoenician god Melqart was walking along a beach with his dog. The dog ran ahead, sniffing seashells along the shore. Melqart called his dog, and he ran towards him, displaying a newly stained purple nose. Melqart found the color so beautiful that he wanted to make a tunic of the same color for his lover, the nymph Tyros. He set out to find sea snails and from these he created the most vibrant dye the world had ever seen.

Tracking the true origins of the purple murex has proven difficult. The earliest evidence of its use dates back around 4,000 years in Qatar. In the first century AD, there was such a craving for purple that author and naval commander Pliny the Elder, whose recipe for making Tyrolean purple survives, dubbed the color craze purpura insania— violet mania. Despite this, however, neither he nor other ancient writers appear to have written precise instructions for producing the dye. An archaeologist traveled to the Aegean Sea to try Pliny’s recipe for herself and was disappointed by the dull grayish-purples (and odious smell) the dye pot produced.

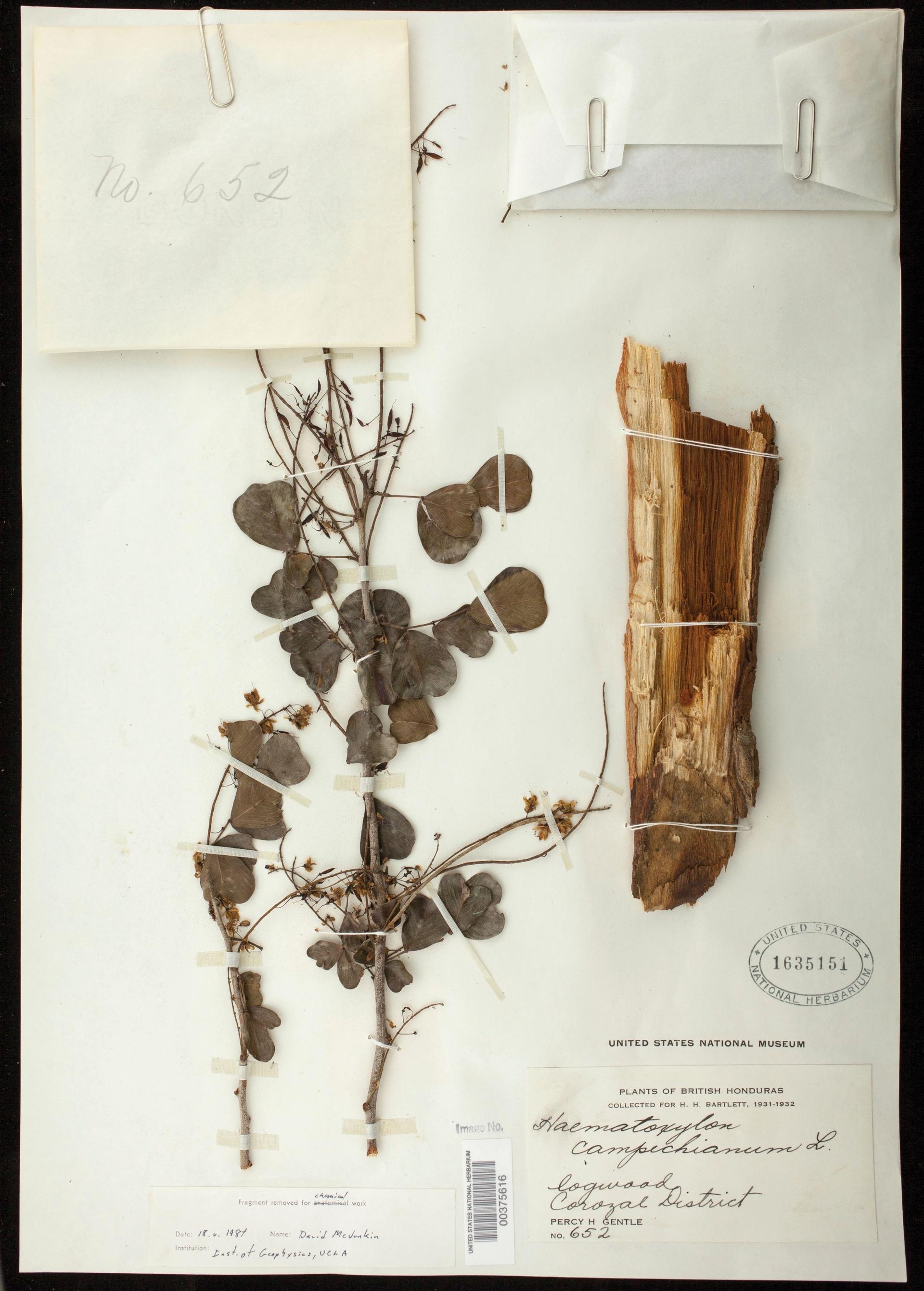

A specimen of logwood Courtesy of the National Herbarium of the United States

Blackbeard ahoy: logwood

Logwood, used to make black dye, thrives in the aquatic landscape of mangroves and swamps along the coast of Mexico and South America. Its trunk is narrow and twisted, and it has clusters of yellow, frothy flowers. The wood is both hard and heavy, and while the outer wood is pale, the inner core of logwood is tinged with a dark reddish brown, hinting at its potential as a colorant. Indigenous civilizations used logwood for several millennia as a dye and as a medicine before the arrival of the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his acolytes. The Aztecs and Mayans treated various ailments with logwood, including anemia, dysentery, diarrhea, tuberculosis, and menstrual cramps.

Logwood quickly gained popularity in Europe. At first, Spain had a monopoly on the trade, and the limited supply meant that logwood became so valuable that it was subject to rampant piracy, mainly by the English. During the reign of Henry VIII, a cargo of logwood was worth a year’s trade of any other cargo. In 1581, Queen Elizabeth I banned the importation and dyeing of logwood, blaming its poor lightfastness, but protectionist trade policy was the most likely motivation for the ban. England had a thriving pastel industry and logwood was a threat. In 1585, a tense trade dispute between England and Spain erupted into a decades-long trade war, and logwood was one of the commodities at its center. Breaking Spain’s monopoly was seen as a key factor in the sinking of the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Yellow sub-aquamarine: solder

Solder’s superiority over other yellow dyes lies in its strength, its ability to remain bright and vibrant over time. Alongside pastel and madder, it formed the “great complexion”, the medieval triad of fast and essential primary dyes. And while solder is the fastest or most permanent yellow, it has nothing on the permanence of blues and reds. There are no natural yellow dyes that have the power to remain indigotin or alizarin. Thus, medieval tapestries often have “the blues”, meaning that sections that were once green become aquamarine over time. These green sections were usually dyed with pastel and solder, and while the yellows of solder fade over time, the blues of the pastel remain, giving the impression that some medieval tapestries are placed under water. .

A Norwegian woman wearing a folk dress. Traditional Norwegian

embroidery used Krapp dyed wool (madder) Søstrene Persen, 1901. Courtesy of The Fallaize Collection, Wellcome Collection

Red-faced cure: madder

Nothing in the aerial aspect of madder indicates that it is a dye plant. It is a hardy herb that flourishes in marshy, moist soil; its lemon yellow flowers (not red) are nestled among small pointed leaves. But the orange-red lumpy roots of the dyer’s madder plant betray it as a source of red dye. Gnarled like the fingers of a fairy tale witch, the twisted roots could be said to possess a kind of color magic, producing a surprisingly wide and diverse palette of reds.

During its long tenure as a colorant, madder developed an association with the military, from the battle dress of the Romans to English red coats. In ancient Greece, Spartans used to dye their clothes red to hide bloodstains, and Napoleon enforced its use on his officers’ uniforms. Rubia tinctorum has also been used medicinally. A 16th century account recommends using madder for bruises and wounds. Famous English physician Nicholas Culpeper prescribed its use for jaundice, paralysis, sciatica, hemorrhoids and freckle removal.

•Lauren MacDonald, In pursuit of color, from mushrooms to fossil fuels: discovering the origins of the world’s most famous dyesAtelier Editions & DAP, 272pp, £37.50 (hb)