On the Burrup Peninsula in northwest Australia, uncontrolled emissions from the petrochemical industry threaten not only the region’s natural environment, but also its rich cultural heritage.

The strip of land is home to the Murujuga rock art, a collection of approximately one million petroglyphs depicting human figures, a cornucopia of animals, and several extinct species. It is also the site of a vast industrial complex including Australia’s largest gas producer, an ammonia plant and a urea plant which started in late April.

Development in the region began in the 1960s but was boosted following the discovery of offshore gas deposits which led to the construction of Australia’s largest petrochemical complex and an ongoing battle between ecologists and industrialists. Although previously reserved projects have been diverted elsewhere in Murujuga National Parkscientists and traditional custodians remain deeply concerned that current levels of acidic emissions from the petrochemical complex are damaging the etchings made in the reddish-brown rocks.

The ancient Aboriginal rock carving known as ‘Climbing Man’, believed to be thousands of years old, on the Burrup Peninsula in 2008. Photo: Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images.

Industrialists operating on the Burrup Peninsula have long denied the impact of emissions on Murujuga rock art, sometimes using imperfect and misleading given to do so, but an investigative journal published by researchers at the University of Western Australia in Conservation and management of archaeological sites end of 2022 makes the case quite conclusive.

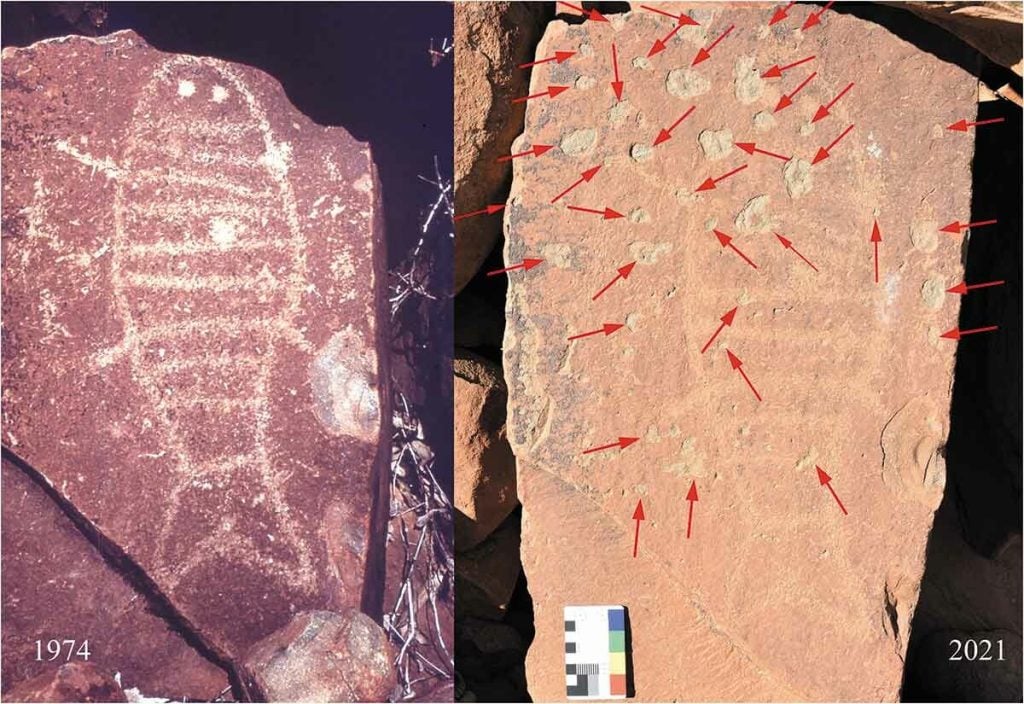

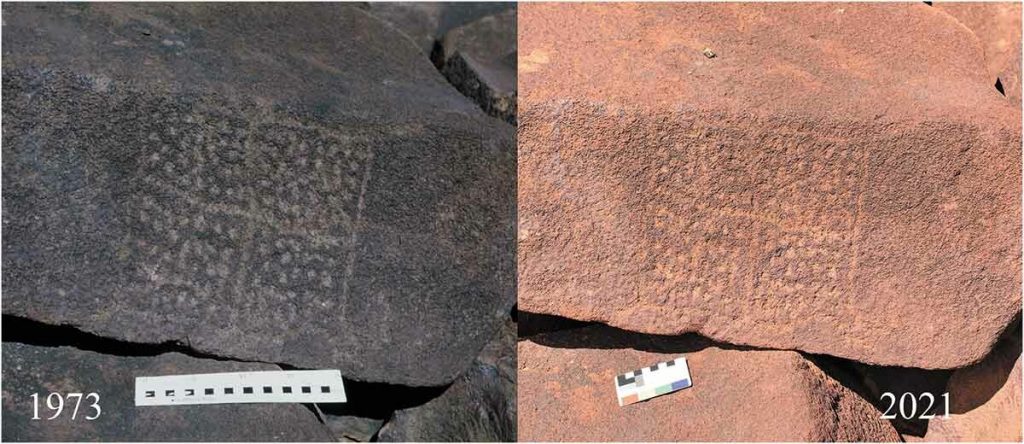

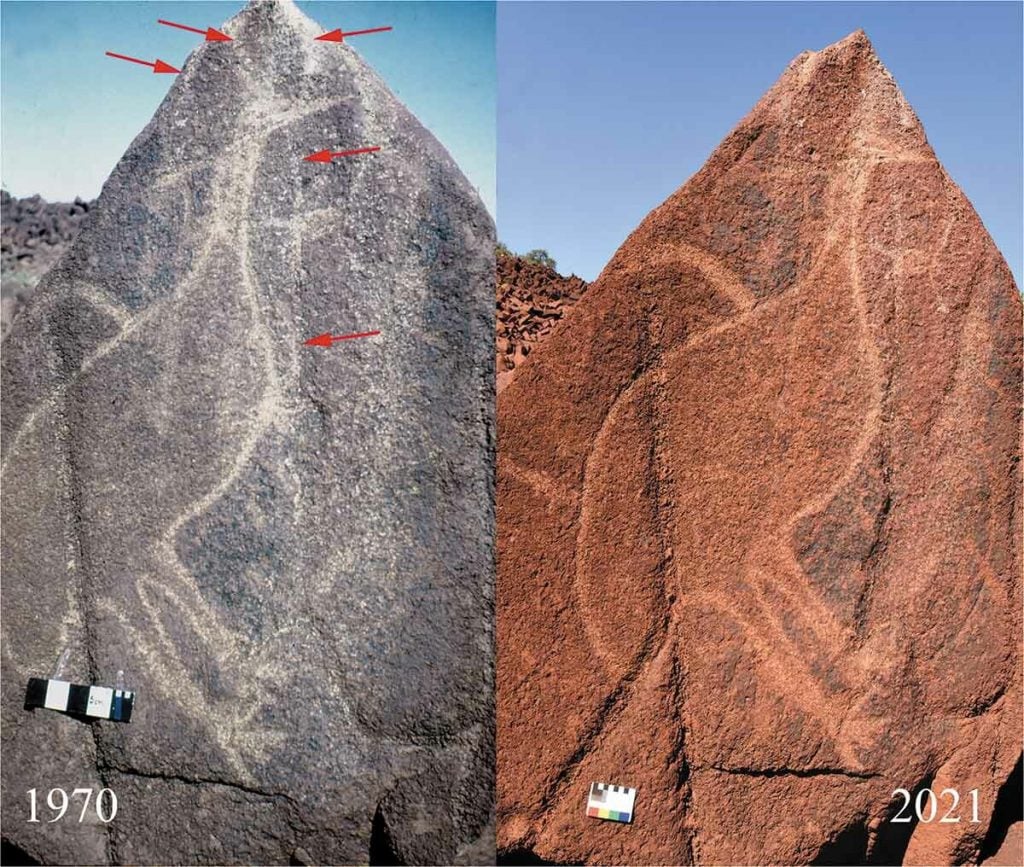

The study, titled “Monitoring Rock Art Decay: Archival Image Analysis of Petroglyphs on Murujuga, Western Australia,” compared 26 photographs of petroglyphs taken before industrialization and compared them to recent photographs. Half of the petroglyphs showed signs of change and two others showed signs of significant damage. With the exception of two petroglyphs, all were located close to the industrial zone.

The article cites three main ways in which industrial activity damages the rocks of Murujuga: mechanical removal during land clearing, acidic dust which, when mixed with water, erodes the surface of the rock, and the increase in the number of graffiti, trampling and theft.

Images comparing the 1974 photo to the 2021 photo show damage to the fish petroglyph, red arrows show peeling rock varnish. Photo: Benjamin Smith ‘Monitoring the degradation of rock art’.

The presence of acidic chemicals emitted by industry is of particular concern to scientists and traditional custodians. The rocks at Murujuga have a patina built up from mineralization, which Aboriginal artists scraped and scraped away to reveal the gray rock beneath and create their images. The paper warns that high concentrations of acid can completely dissolve the outer veneer of these rocks.

“If emissions are reduced quickly at Murujuga, the evidence presented in this paper suggests that damage to rock art may be limited and this extraordinary place may remain largely untouched for future generations,” the authors wrote. .

The rock art at Murujuga dates back over 40,000 years, but came to a halt in 1868 when European settlers massacred the local Yaburara people in what is known as the Flying Foam Massacre.

See more images from the study below.

Images comparing the 1973 photo to the 2021 photo show damage to the patterned petroglyph. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring the degradation of rock art”.

Images comparing the 1988 photo to the 2021 photo show damage to the petroglyph thought to be from lightning. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring the degradation of rock art”.

Images comparing the 1970 photo to the 2021 photo show damage to the bird petroglyph. Photo: Benjamin Smith “Monitoring the degradation of rock art”.

More trending stories:

Sculpture depicting King Tut as a black man sparks international outrage

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.