Brigid Berlin was a debutante, a rebel, an artist, a muse.

She’s not a household name to many even today, but in the inner-city demimonde of the 1960s and 1970s, Berlin became a cult figure, famous as Andy Warhol’s playful sidekick, his muse and the star of his 1966 experimental film. Chelsea Girls. She was also an intriguing artist in her own right, who many believe picked up the Polaroid before Warhol himself, and collaborated with many of the leading artistic names of her day. Berlin, died in New York in 2020 at the age of 80, was in many ways a Consummate contradiction, and the scope of his heady, and at times tense, life and legacy are always front and center.

NOW, “The heaviest,” a new exhibition at Vito Schnabel’s downtown space, curated by Alison M. Gingeras, shines a spotlight on Berlin as an artist with a complex practice ahead of its time, and presents its provocative legacy to a new generation. The exhibition is an intense and dizzying portrait of an unwieldy creative force, and follows Berlin’s childhood as a daughter of New York high society, through her famous years in the Warhol’s Factory circle, to to her independent artistic career and exhibitions, and well into the latter years of her life when she returned to the monetary circles of her childhood. This full-loop presentation brings together Berlin’s work in Polaroids, audio recordings and even tapestry.

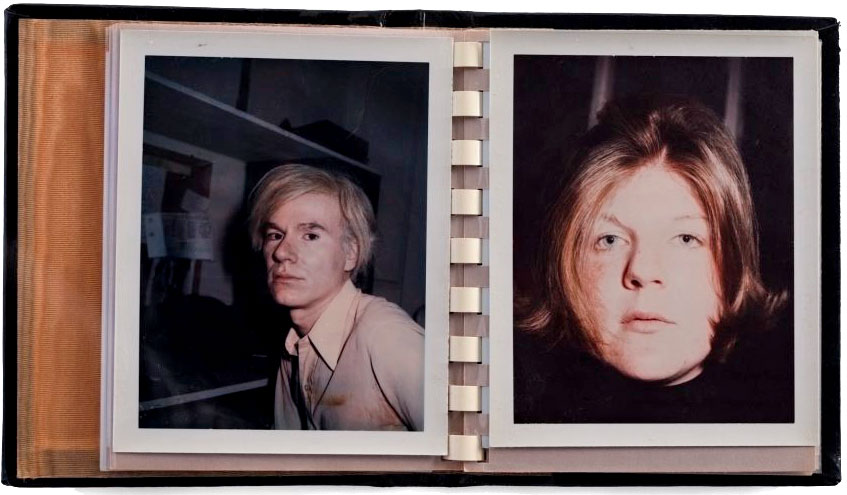

Bridget Berlin, Mr. and Mrs. Brigid Pork. © Vincent Fremont/Vincent Fremont Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

Bridget Berlin, Mr. and Mrs. Brigid Pork. © Vincent Fremont/Vincent Fremont Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

Much of the work included in the exhibition is presented for the first time; Gingeras spent several years planning the exhibition, researching materials in artists’ archives and in the Berlin estate. The idea for the exhibition was born while Gingeras was writing an essay for the 2019 catalog Warhol’s Women. “I was researching these women who were major agents of creative interchange in Warhol’s life, and realized how Brigid’s own contributions as an artist were read through Warhol’s prism . It rubbed me the wrong way,” she explained. “This exhibition really became an opportunity to look at her holistically both in a biographical sense and as a deeper dive into her relationships and position in the art world, particularly in the 1970s.”

Berlin was born in 1939, the daughter of sought-after socialite Muriel “Honey” Johnson and Richard E. Berlin, president of Hearst’s media empire for more than three decades. Her father’s powerful position placed the family at the pinnacle of upper-class society – Nelson Rockefeller, Richard Nixon and the Windsors were all family friends who sought advice. But Berlin’s stark childhood was anything but idyllic. The exhibition begins with staged saccharine childhood photographs and Christmas cards from Berlin and her sister. These perfected images are juxtaposed with display cases of letters exchanged between Berlin, at boarding school, and his mother; Often heartbreaking, the letters document his mother’s ruthless reprimands in Berlin over his weight (his mother infamously fed Berlin amphetamines as a child in an effort to control his figure), but also allude to Berlin’s rebellious nature. A letter from the Berlin schoolmaster details a night of drinking gone wrong in sordid and comedic detail.

Bridget Berlin, Untitled (Tit Print) (1996). © Vincent Fremont/Vincent Fremont Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

“Her family’s shame around her body was the catalyst that catapulted her into the so-called rebellion that brought her to the factory gates,” Gingeras said as he walked through the exhibit.

The Factory and Warhol, the father of Pop, are certainly present in “The Heavyest” but here Warhol is represented through the eyes of Berlin, and not the reverse. A selection of Berlin’s many thematically compiled Polaroids photo books are on display, including one with “Mr & Mrs. Pork” embossed on its cover, a reference to animal names the friends have kept to each other. In this book, Berlin and Warhol are presented in photographs side by side, a creative dyad rather than artist and muse.

But while the factory can certainly be felt, it is the autonomous Berlin artist who is the main focus of the exhibition. Perhaps the birthright of his high-society background, Berlin, the exhibit makes clear, had a way of permeating many worlds. While Warhol was perhaps her most famous companion, she too was embraced by the “heavy” machos of the art world and counted Willem de Kooning, John Chamberlain, Larry Rivers, Donald Judd, Richard Serra, James Rosenquist and Brice Marden, among his friends. These artists also all appear in her Polaroid photo books, and their friendships are detailed in exchanged letters, postcards, as well as portraits of Berlin itself, including one by Ray Johnson, featured in the exhibition.

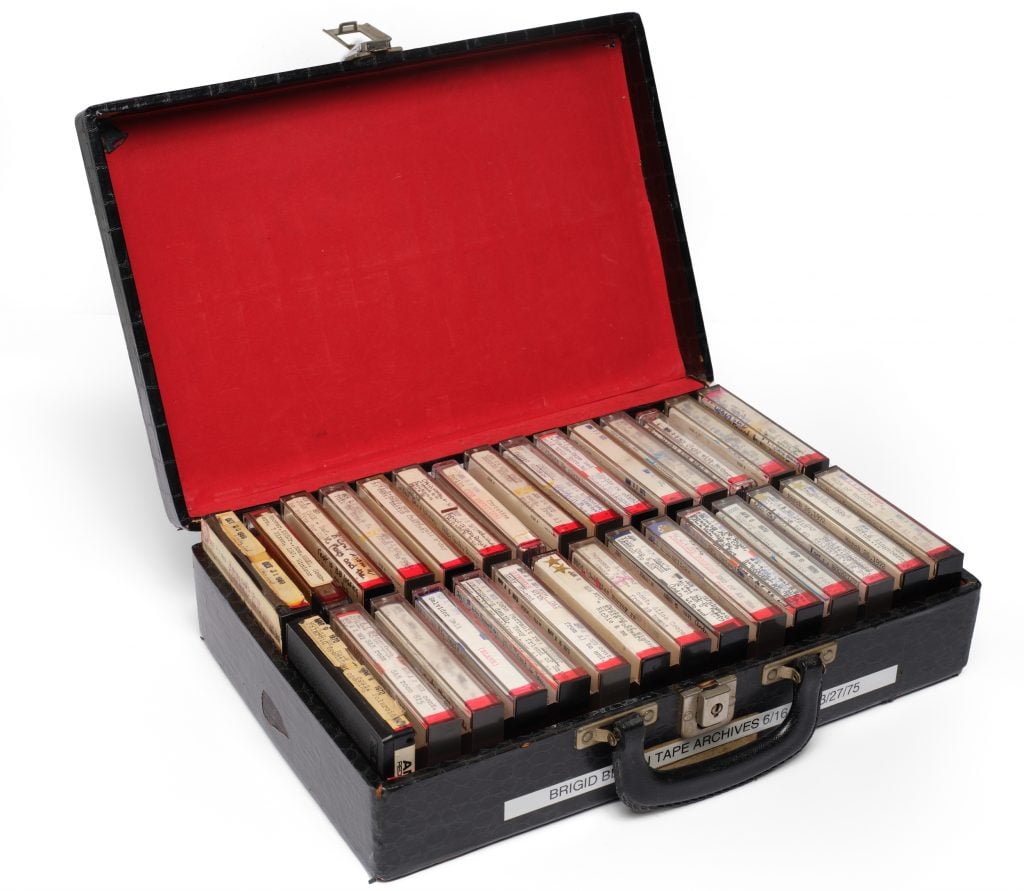

Cassettes from Brigid Berlin Audio Archive. © Rob Vaczy and Pat Hackett. All rights reserved.

Although Berlin often focuses her lens outward, when looking at herself, her work is particularly satisfying. Among the most evocative works in the exhibition are Berlin’s so-called “tit prints” which, as the name suggests, are colorful impressions the artist created from her breasts. For a figure that has been so often judged by looks, these prints feel wonderfully personified. “Body positivity didn’t exist back then and she really brazenly embraced her body as a creative tool,” Gingeras shared in a chat.

However, Berlin’s fascination with the body extended beyond his own, and certainly the most irreverent and downright funny work in the exhibition is his infamous “Cock Book”. Done between 1968 and 1974, Berlin won a notebook stamped with “Topical Bible” on the cover, and asked mostly male artists to depict their penises in its pages. Filled with drawings, photographs and collages, the book’s many contributors include Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dennis Hopper, Cy Twombly, James Rosenquist, Ray Johnson, Cecil Beaton and Robert Smithson, among dozens of other household names.

Installation view of “Brigid Berlin: The Heaviest,” curated by Alison M. Gingeras. Photo: Argenis Apolinario. Courtesy of Vito Schnabel Gallery.

While the ephemera of these friendships serve to place Berlin at the heart of the art scene of the time, the exhibition is right to point out that his recognition as an authentic artist also came from the dealers. In 1970, Berlin was the subject of a solo exhibition at the renowned Heiner Friedrich Gallery in Cologne, Germany – his first solo and one that featured his audio tapes and Polaroid photographs. “The Heaviest” is remarkably the first exhibit since that flagship show to feature these recordings, which encompass calls and conversations between Berlin and loved ones. The recordings are surprisingly transporting. In one recording, Berlin’s mother castigates her for her association with the Factory milieu, accusing Berlin of using drugs. In another, Warhol begs Berlin, when she says she tore up her Polaroids, and he offers to pay her a penny apiece for them (then, when she hesitates, three pennies). These snippets are oddly prescient of our contemporary fixation on reality entertainment, and utterly absorbing.

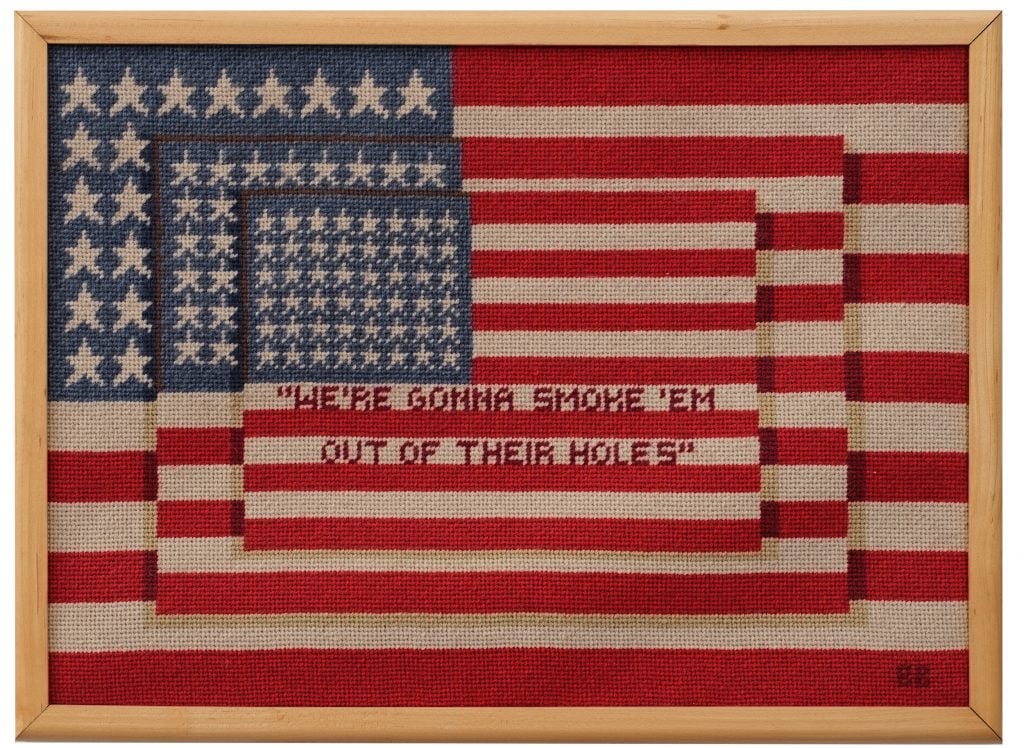

Bridget Berlin, Untitled (Jasper Johns Flag) (circa 2002). © Vincent Fremont/Vincent Fremont Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. Collection of Vincent and Shelly Fremont, New York.

Perhaps what makes Berlin so intriguing as a creative force is its simultaneous adherence to and transcendence of the norms of its time. As she eschewed her conservative childhood, she sought the approval of male artists, what Berlin calls her “absorbed misognise.” His political views could be anything but polite. Later in life, Berlin abandoned the inner-city sphere altogether, moving into a downtown apartment. which is garish in its own way.

In recent decades, Berlin has not completely abandoned artistic creation. Among the show’s interrogative highlights are several needlepoint pillowcases she made in the early 2000s, some recreating New York Post covers, covers that Berlin said reminded him of his father, another mixing those of Jasper Johns Flags with chauvinistic language that can sound as American as a can of Campbell’s soup, if only the darker side of the dream. The exhibition concludes with a collection of artistic homages to Berlin, from the striking portrait of the artist produced by Kate Simon in 2008 to a recent painting by Elisabetta Zangrandi – the interpretations are varied and appear like offerings deposited in the reliquary of a mythical creative life.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.