The film Insidewhich hit US cinemas last month, is a cuddly art story – a tale built around a crime gone wrong.

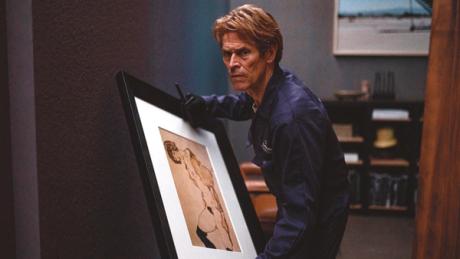

Here, American actor Willem Dafoe plays an art-for-hire burglar in a film that’s more premise than story. This is the starting point for a solo performance by Dafoe, whose character, a burglar named Nemo, is lowered by helicopter into an art-filled New York penthouse. The owner of the apartment would be in Kazakhstan; her place is filled with items as expensive and generic as the art on the walls: think Architectural Summary. Nemo’s mission is to steal works by modern master Egon Schiele.

Forget the age-old trope of the hungry artist – now we have the hungry art thief

From the start, the feeling sets in that this robbery is a victimless crime; that a person who owns such a luxurious apartment can afford to replace everything that was stolen from him. Nemo is stuck there when an alarm goes off and seals the doors and windows. This moment transforms the trapped criminal into a victim. Forget the age-old trope of the hungry artist – now we have the hungry art thief.

Desperate, Nemo searches for a solution to this lost arthouse dilemma, damaging or reorienting the art as he struggles for a way out, even impersonating (or saluting?) Ai Weiwei with a tower of furniture to break through the skylight. . Staying alive takes precedence over everything else. You can’t eat a Schiele, or can you? What about the tropical fish in the elegant aquarium? The destructive frenzy of Nemo is perfect fodder for the mainstream target audience who might be skeptical of what constitutes contemporary art these days.

The survivalist fable in the confined space unfolds like a theater. In what may seem like an over-the-top improvisation with long close-ups, Nemo grapples with his loneliness, hunger, thirst, and extremes of hot and cold when the temperature controls (for the art) go haywire. Losing his mind, Nemo begins drawing on the walls, raising the obvious question of whether art is the ultimate form of madness. Nemo’s tortured situation is ambiguous: art is the unaffordable treasure that attracts a thief (and attracts us, the audience, as voyeurs), but it has no value because Nemo risks dying alone.

Inside is the feature debut of Vasilis Katsoupis, who directs television commercials in Greece. The screenplay is by Katsoupis and British filmmaker Ben Hopkins, with film art (actual works by Francesco ClementAdrian Paci, Maurizio Cattelan and others) chosen by the Italian curator Leonardo Bigazzi.

Dafoe, who played Jesus in the 1988 epic The Last Temptation of Christ, is more of a John the Baptist character here, stranded in a wasteland of high-rise luxury. But Dafoe is nothing if not adaptable: In his early 60s, he played a 37-year-old Vincent van Gogh in At the door of eternity (2018), directed by Julian Schnabel. One of his finest roles was in The Florida Project (2017) as the manager of a motel full of needy families stuck in the airport landing strip that serves Disneyworld.

Unexplained plot holes

Katsoupis’ camera captures the privilege of icy skyscrapers, with the hard edges of slate and steel and rarefied devices. As Dafoe scrapes that veneer, all Katsoupis has to do is leave the camera on. The minimal storyline may have more unexplained holes than the furniture Nemo rips apart, but it’s an actor’s flick, with Dafoe roaming the set like a man who’s never encountered a grimace he doesn’t like. Even for him, it’s still a struggle to maintain the audience’s interest, locked in a small space with no one but yourself to talk to for 105 minutes.

Inside is an exercise – ultimately a confusing, exhausting exercise – for a performer ready for a challenge. Dafoe will move on to the next tortured character, while we wonder how no one in the building heard the deafening sound of a helicopter hovering overhead when Nemo first arrived.