Kylie Manning’s paintings are like looking over the edge of a precipice. In his studio in Ridgewood, Queens, his painting Pareidolia (2023) hangs on a paint-splattered wall. Bblue and green pigments pulsate across the canvas like streams, and as the afternoon light streams in through the window, the paint appears to shimmer, flecks of light leaping like embers across the canvas.

Movement is everywhere in the work at once, creating a vertiginous and dizzying effect. Pareidoliawith another table, You in me, me in youhung nearby in the workshop, were the inspirations behind the scenography and costumes of highly anticipated choreographer Christopher Wheeldon new ballet “From you in me” currently performing at the New York City Ballet’s Spring Gala. Wheeldon had been captivated by Manning’s paintings when he visited ‘Both Sides Now’, his first exhibition with the Pace Gallery, at the Los Angeles space in the fall of last year. Fascinated by the dance passages that characterize Manning’s paintings, Wheeldon, in an unusual move, brought her in as a close collaborator throughout the ballet’s development process, with Manning guiding the set design and costumes (Manning’s titles, one can notice it, are often titles or lyrics of songs).

“Come see how the painting changes as you approach,” she told me. Manning’s eyes move over the work, then watch my eyes move over the work. She is nine months pregnant and her blonde hair is braided around her head on an unusually sweltering April day. As I approach the painting, I have the strange sensation of falling backwards, as if waking up from a dream, and I need to reorient myself.

Kylie Manning, Scorpion Bay (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

“We feel it rising,” she observed, “We don’t quite understand the magnitude of what we are seeing that is not accidental. I want to feel that there is a wave crashing over us.

Currently, Pace Geneva is presenting “You in me, me in you(until May 13), Manning’s first exhibition in Switzerland. The exhibition brings together paintings conceived in parallel with his collaboration with the ballet. These jobs flourish in an intermediate space, landscapes suggested but never revealed, figures, painted with a flexible expressionism, emerge then recede in a pigmented mist (Manning’s two paintings for the ballet are atypical in that they are absent figures, the dancers instead occupying this bodily presence). Although the works are bubbling with energy, its process is slow. She builds her canvases by superimposing glues and rabbit skin oils, in a process close to Caravaggio and Vermeer in its traditional materiality. Then she starts removing items.

“It’s like a hiding place,” she says, placing her hand on a painting she has just started. Manning leaves evidence of his process for viewers to witness. “I think of old surfers whose bodies are covered in freckles and scars. Their bodies are full of scars and stories. I think of the webs, of the construction of this stored energy,” she said.

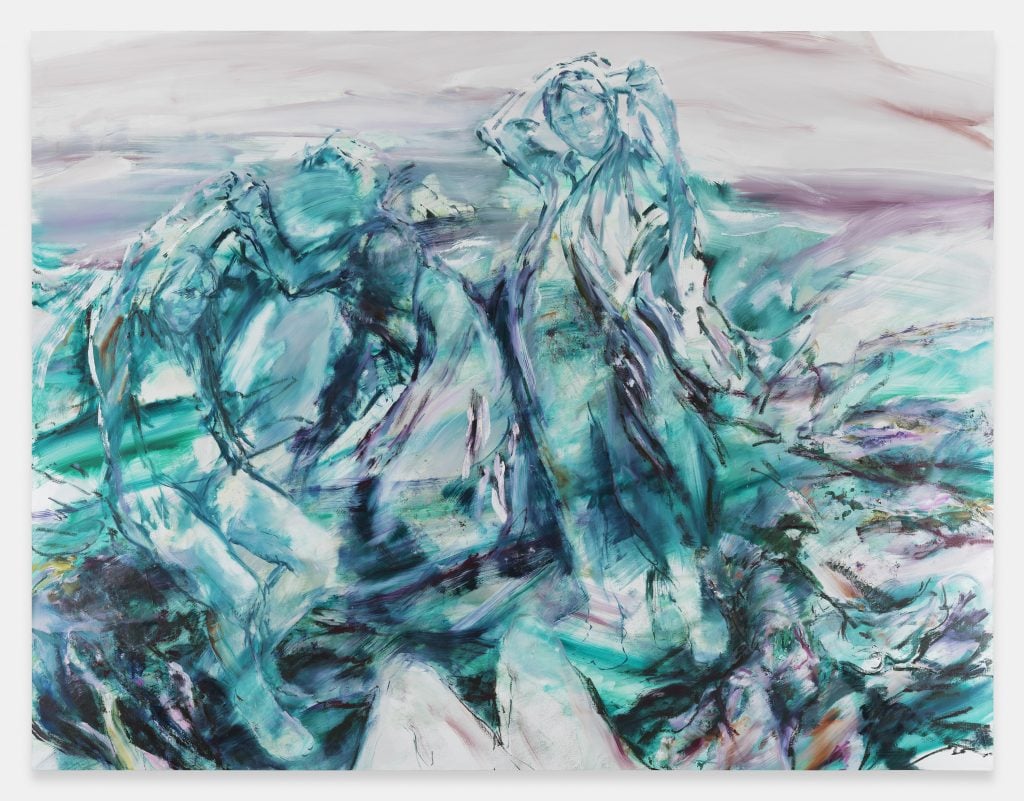

Kylie Manning, Archipelago (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

In his most recent works, brushstrokes of color sweep and glide across large-scale canvases. Its hues are enhanced again, in moments, with intense emeralds and fuchsias evoking forests and oceans and icy sunsets. “These colors are of a colder, more northern climate than the LA works, which had a kind of warmth to them,” Manning noted.

Wilderness, Manning hints, again and again, in oblique allusions to his own life. The artist grew up one of five children, her parents both art teachers, living between Juneau, Alaska, where she was born, and San Blas and Sayulita, Mexico, where she spent part of her childhood. “I was raised literally like a wild animal,” she told me. “All of our photos show us running on the beach as kids in Mexico or in the woods in Alaska.” On one level, his paintings are bold warnings about the power of nature and our precarious relationship with the world we inhabit.

“Seeing powerful art in New York is the closest thing to experiencing being in nature,” she told me. Manning has had intense encounters with nature herself. Knowing she wanted to pursue an MFA, but lacking funding, Manning earned a captain’s license and operated a 500-ton commercial fishing boat in the Pacific to help pay for her tuition at the New York Academy of Art. She is also an avid surfer. Standing in front of his canvases, one can feel the tides – in the push and pull of his images and the gleaming, shimmering sense of light. In a work like Here you are backJMW Turner’s stormy seascapes come to mind, along with other large-scale paintings of the sea from Winslow Homer to by Theodore Gericault Medusa Raft.

Kylie Manning, Always be on my feet (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Pace.

Manning’s paintings are quietly confident, allowing room for nuance and multiple perspectives. When I tell her that I feel like she comes out of nowhere, she laughs generously. The artist, who is 39, has been painting for almost 20 years. But his rise to the limelight was hasty. She came to Pace Gallery through Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle. The two met at a Joan Synder exhibition at the Gallery of Canada in 2020. Boyle, who was working there at the time, was struck by her thoughtful questions. The two stayed in touch for months. Boyle was unaware that she was a painter for a while. “A lot of people don’t believe it. But Kylie is very, very modest. It wasn’t until she was preparing a solo exhibition that she shared the work with me and invited me for a studio visit Boyle explained, “I was immediately captivated. The rest is history.”

Boyle thinks Manning has a force of vision all his own that honestly speaks to the changes in art that we are only now beginning to recognize and name. On the one hand, Boyle notes the androgyny of his characters. Manning’s characters are neither male nor female, young or old. Defined passages of figuration give way to clouds of amorphous form, as if viewing a figure through a mist. Boyle aligns these asexual figures with Manning’s formal qualities, an amalgamation of abstraction and figuration. Manning herself does not see these modes of painting as opposites. “It’s a range of information given,” she said.

Kylie Manning, Here you are back (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Pace.

Seeking cohesion in the real world is also madness. In her paint Always be on my feet (2023) a nose and a mouth can be gleaned from a character’s raised hand. This visual language is that of gestures, small distinct movements, the curve of a neck, the turn of a leg, which evoke masculinity and femininity – in a resolutely dancing way. In Archipelago, two figures are seated next to each other, as if resting on a bed, a figure’s belly is curving, possibly a pregnant woman’s belly. Looking again, however, I wonder if I am reaching any meanings; his painting title, Pareidolia, after all, refers to the brain’s tendency to recognize patterns or figures in amorphous forms. In other words, we might see what we expect to see versus what is actually there.

Even so, Manning’s characters are both haunting and heavenly in their forms. I told him these figures reminded me of angels, and Manning explained that on some level the paintings emerged from a time of mourning, his own treatment of world events in 2020 and 2021.”The loss that we couldn’t feel when we were surviving began to seep through the cracks in these works,” Manning said.

When asked if she believed in an afterlife, Manning said she preferred not to place her own values on the works, but rather let them speak for themselves. They speak, the images, the whirlwind of the world beyond what is known, of the continuity of change.

When Manning works, she surrounds herself with canvases that she builds simultaneously, thinking of these works as a kind of family unit. The family, in its constantly changing nature, is one of his recurring centers of interest (the artist sometimes uses his own hands to replace those of his mother, so similar are they). Pregnancy, she says, heightened her awareness of our constant state of metamorphosis.

“But change can have a quality of detachment,” she said, surrounded by her latest paintings, “and it can be amazing.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.