The lowest paid workers in the public art sector in the UK are often those who create the art.

This is the sobering conclusion, if not the total surprise, to be drawn from Structurally fucked, a recently published report on artists’ pay and conditions commissioned by one, Britain’s largest artists’ association. Compiled by Industria, an artist-run organization that “examines and challenges” conditions in the art world, the report is based on 104 anonymous responses to the Artist Leaks project, which surveyed artists about their experiences working on public commissions in the UK.

“There is a culture of low fees, unpaid work and systemic exploitation”

The data collected reveals “a culture of low fees, unpaid work and systemic exploitation,” according to the report. Among the key findings, artists earned a median wage of £2.60 per hour, well below the UK minimum wage of £9.50 per hour (at time of research). Block fees were a common form of payment, resulting in 74% of respondents saying they felt the artist’s fee was “unfair” in relation to the number of hours worked; 76% said their fees were below minimum wage.

“It’s a stark reminder of the precariousness of artists’ careers,” says Julie Lomax, the general manager of one, which has around 30,000 members. “You can keep the market confident and make sure the market bubble doesn’t burst. The problem is in the public sector,” she says, aware that in 2022 the UK art market has re-established its status as the second-largest in the world, according to Art’s latest annual art market report. Basel and UBS. “The visual arts are structurally underfunded,” adds Lomax.

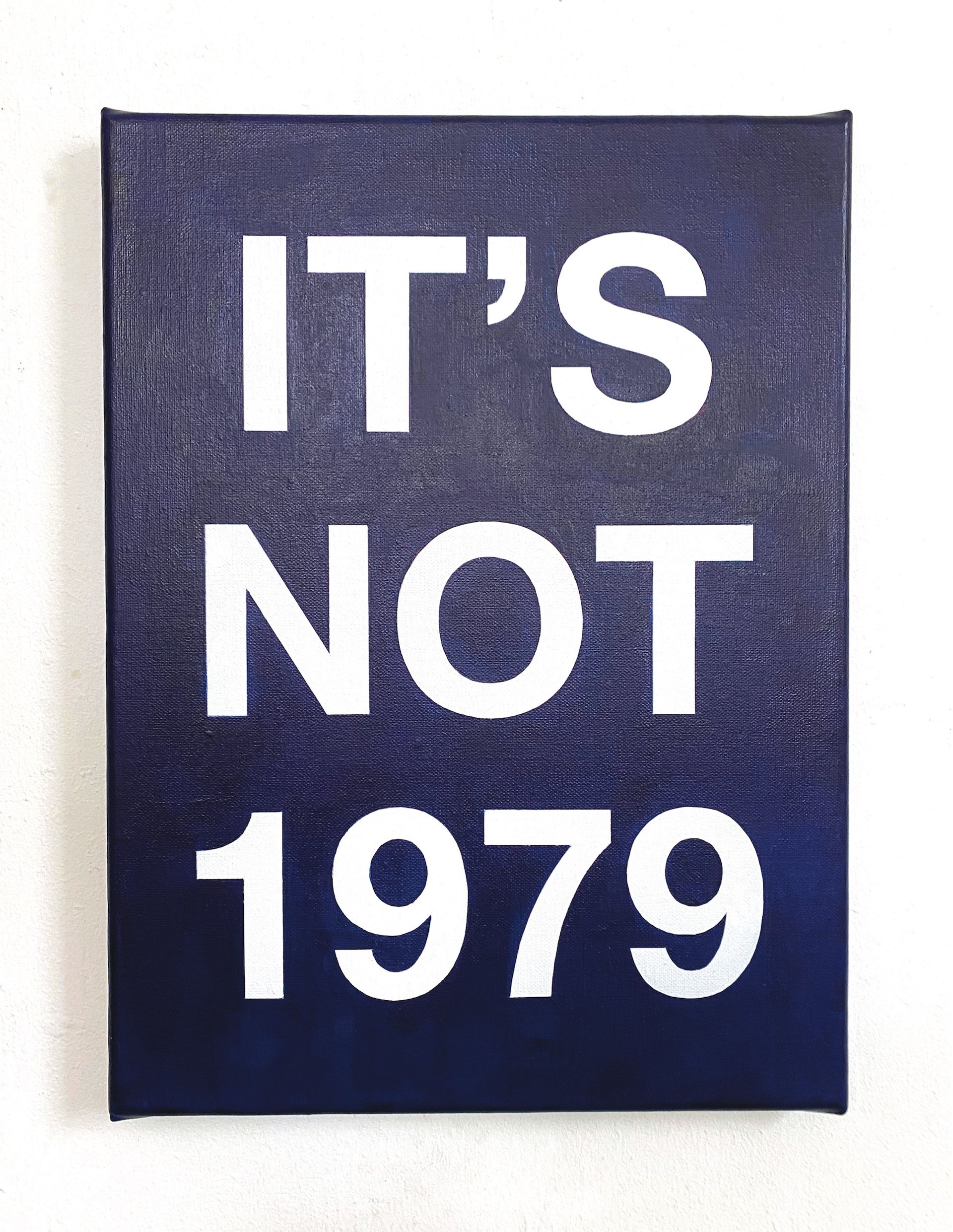

by Mark Titchner It’s not 1979 (2023), one of his last textual works, which recalls the rise to power of Margaret Thatcher

©Marc Titchner

Since 2008, public funding for the arts in Britain has shrunk by 35%, with local government spending on the arts falling by 45%, according to the report. Funding for the visual arts in England is a patchwork mix of grants from the government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), supplemented by support from local authorities.

Thanks to the cataclysmic hubris of Britain’s financial sector, from September 2007 to December 2009, the then Labor government found itself spending £137 billion of taxpayers’ money bailing out banks, according to the Library of the House of Commons. Although as of January 2018 £114bn was clawed back, Tory administrations remain determined to ‘balance the books’ by cutting public spending at national and local level wherever they can. Arts funding is one of their easiest targets, with predictable results.

Summarizing his recent experience of a publicly commissioned project in the West of England, which matches many anonymized testimonies in Structurally fucked, artist Dominic from Luton says: “Badly paid. Project abandoned at the last moment after a year of work. The remaining funds, amounting to 50%, are used for the organization’s program, not for the commissioned project. Lack of professionalism. A request from the artist for a contract refused by the organization.

But by highlighting how little artists are earning, is the report inadvertently playing into the Conservative government’s cost-cutting favor?

bottom of table

In 2020, the Institute of Fiscal Studies and the Department of Education published a study which showed creative arts at the bottom of the UK graduate earnings results table, fueling negative perceptions of it as a “low value”. This only reinforced the findings of the government’s 2019 review of education and post-18 funding, chaired by former investment banker Philip Augar, which showed that the creative arts were the subject of degree that was costing the government the most in defaulted student loans. While acknowledging that the creative arts ‘make a strong contribution to the economy’, the report questions whether ‘the sheer number of students’ taking these subjects is ‘good value for taxpayers’ money’ .

In 2021, the UK government continued with plans to cut funding for art and design courses by 50%. That year, when Rishi Sunak, another former investment banker, was chancellor, the Guardian reported a source close to the government saying that “the Treasury is particularly obsessed with negative performance in creative arts subjects”.

The creative industries sector contributed £109bn to the UK economy in 2021, according to the government’s own figures. The financial services sector contributed £174 billion in the same year. But, as Martin Wolf, the leading economics commentator on the FinancialTimesemphasizes in his recently published book The crisis of democratic capitalism, “The financial sector wastes both human and real resources. It is largely a rent extraction machine. Was the £137 billion bailout of failing UK banks in 2007-09 good value for taxpayers’ money?

A lucrative private sector

It is important to expose the little money that most artists earn from British public commissions. But, in a political climate where notions of “value” have become increasingly reductive, it is also worth pointing out that many artists earn a lot of money in the private sector.

At the top of the market we have the highly demanded young British artist Jadé Fadojutimi. Last October at Frieze London, Gagosian’s solo presentation of six new Fadojutimi summaries sold for £500,000 each. If the traditional 50-50 gallery-artist split had been observed, Fadojutumi would have earned £1.5million from a single stand at an art fair.

“Of course she,” Lomax said. “But that’s a very small percentage of artists.”

True, but thanks to the ever-increasing price on the primary market for contemporary works with coveted names, a sizable cohort of British artists, many under 40, could earn at least £200,000 a year from gallery sales.

Instagram and online initiatives such as the Artist Support Pledge have transformed the buying power of artists without gallery representation

And then, further down the price scale, there’s how Instagram and online initiatives like the Artist Support Pledge (ASP) have transformed the buying power of artists without gallery representation. Since its inception in 2020, the ASP portal has enabled its thousands of participating artists to sell more than £100m worth of work at a maximum price of £200, according to Matthew Burrows, its founder.

“I didn’t think my work would sell, but it did. It just snowballed. I had waiting lists for works,” says Zarah Hussain, a London-based artist whose practice is inspired by the geometry of Islamic art. Encouraged by her success on ASP and Instagram (where she has sold paintings online to collectors for up to £8,000), Hussein quit her job as a freelance television producer in 2021 to become a full-time artist. Last year she earned between £35,000 and £40,000 and was hired by the Grosvenor Gallery in London, which successfully exhibited her work at the Art Dubai fair.

“You can’t sit around and wait for a gallery to come to you”

“I never thought I would earn so much money from my work,” says Hussein, who now sits on the board of one. “You have to have an entrepreneur. You can’t sit around and wait for a gallery to come to you,” she adds. Recently, for Ramadan, the artist made a light piece for the London branch of the American advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy, for which she charged £300 a day for five days.

Citizen engagement

But some artists remain staunchly committed to working in the public domain. Mark Titchner, who was shortlisted for the 2006 Turner Prize and enjoys making art for the “places we share”, is currently exhibiting, in collaboration with the Changing Room Gallery, enigmatic On Kawara-like paintings at the club House of St Barnabas in Soho to benefit the homeless.

“We know where arts funding is going,” says Titchner. “It’s definitely getting harder and harder. There is an assumption that “if you don’t take the job under those terms, we’ll get someone else to do it,” adds Titchner, describing the study’s findings. Structurally fucked report as “shocking”.

Join a union, protect yourself with a contract, keep a log of hours worked and stop working for free

The report does, however, contain practical recommendations for artists to improve their working conditions and pay better, even as public funding dwindles: join a union, protect yourself with a contract, keep a diary of hours worked and stop working for free.

Artists should “take collective responsibility,” says Lomax. “It is possible to build new exchange economies.”

Artists are increasingly doing this by selling their work outside the gallery system and connecting with new types of private patrons. After all, it was not the artists who fucked up the old economic structures. Maybe the Treasury should remember that.