“A picture is worth a thousand words”, likes to say Bernie Krause, “but a soundscape is worth a thousand pictures”. The sound artist and bioacoustician has tirelessly researched and recorded the soundscapes of the natural world for 50 years. As he travels the planet, he has captured every wild sound imaginable, from charging elephants and rattling whales to chattering monkeys and chirping birds. Lots of birds.

Krause coined a scientific term for these animal concerts: biophony. Krause’s recorded biophonies – over 5,000 hours of 15,000 species in 2,000 habitats, land and sea – are now part of a new art and sound exhibit in San Francisco titled “The Great Animal Orchestra.” It’s a moving sight to behold in person, not just for its life-affirming soundscapes and dazzling data-driven displays, but also for the emotionally charged – albeit inconvenient – truth that the number of animals is in sharp decline in all the ecosystems of the world.

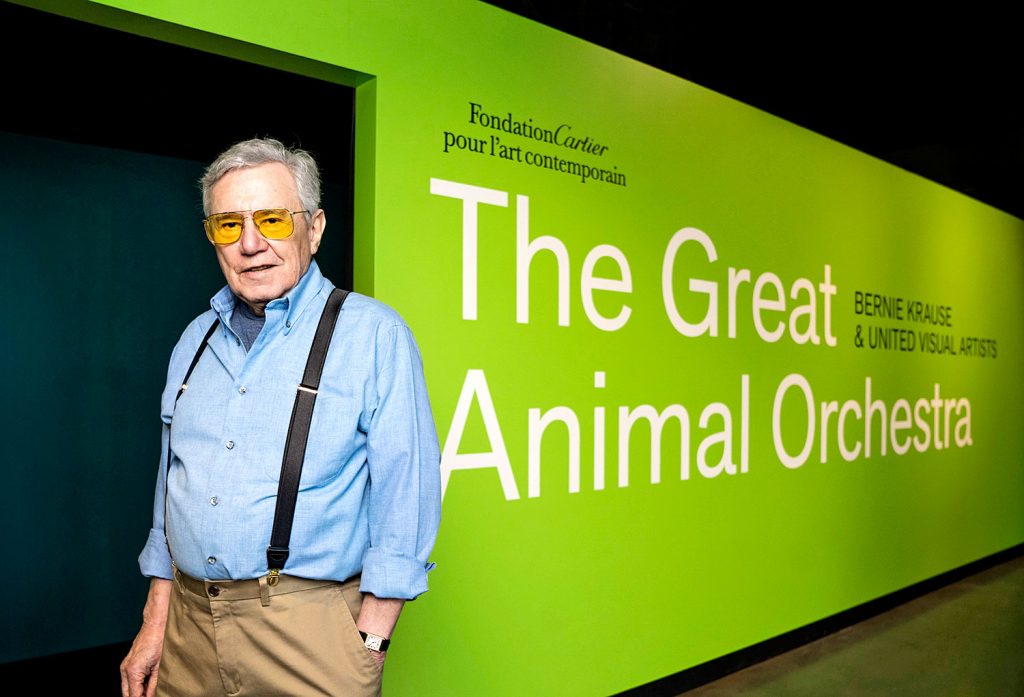

Bernie Krause. Courtesy of Exploratorium.

Named after Krause’s 2012 book, the mighty show runs through October 15 at the Exploratorium at the Embarcadero in San Francisco. (The science and technology museum was the first of its kind when it was founded in 1969 by physicist Frank Oppenheimer, who studied museums in the United States and abroad on a Guggenheim Fellowship before moving on. design it.)

Imagined by Hervé Chandès, artistic director of the Cartier Foundation, “The Great Animal Orchestra” began its world tour in 2016 by integrating the collection of the foundation. For its Paris debut, Cartier commissioned an original work from New York-based Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang, along with photographs by Hiroshi Sugimoto and Manabu Miyazaki. The exhibition has since traveled to Seoul, Shanghai, London, Berlin, Sydney and New York.

“This moment is very touching for all of us, and especially for me,” Chandès said at the San Francisco opener, via video from Paris. He explained that it was while reading Krause’s book that he was inspired to create the immersive exhibition and support it through Cartier. “Aesthetics is the gateway to knowledge and ‘The Great Animal Orchestra’ is a meeting point of art, science, beauty, knowledge – and, of course, a warning about the decline of the wild world, biodiversity and the beauty of life itself.”

The San Francisco stop is the first on the West Coast and the closest to Krause’s home in Sonoma, Northern California. It’s there that candles visited Krause and his wife Katherine in 2014, auditioning clips of the couple extensive archive of animal sounds and first imagine the format for “The Great Animal Orchestra” – which he thought amounted to “the art of paying attention”.

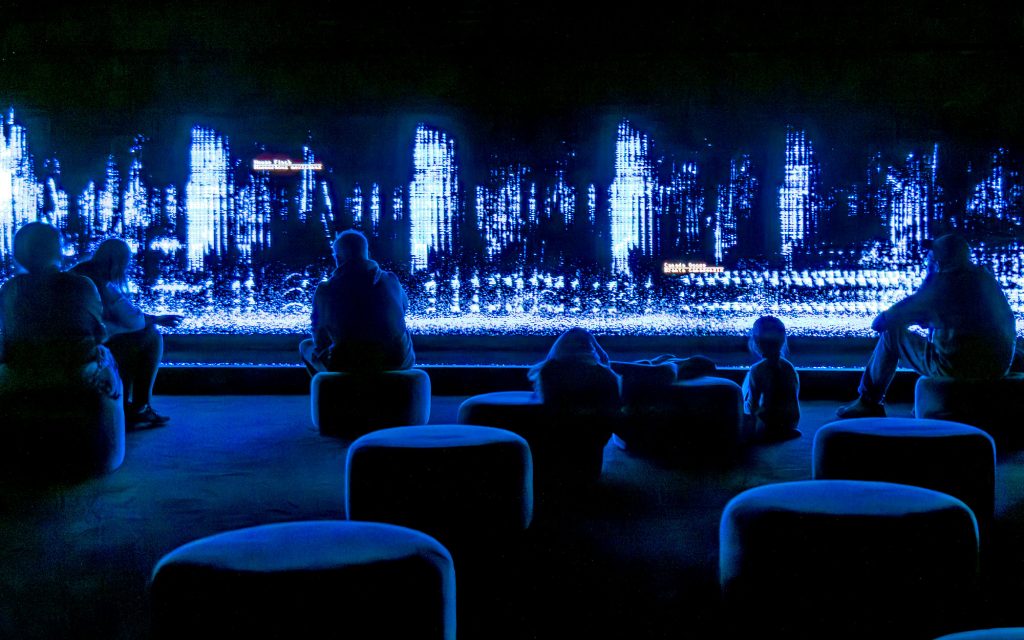

View of the exhibition “The Great Animal Orchestra” by Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists. Courtesy of Exploratorium.

The centerpiece of the show is a stunning immersive installation by United Visual Artists. The London-based collective worked closely with Krause to convert their field recordings into life-size visualizations, or spectrograms, creating a three-dimensional environment that envelops the viewer. In a darkened room at the center of the exhibit, these spectrograms shimmer as a chorus of animals becomes audible, illuminating the walls of the space with detailed visual representations of sound – the upper registers populated by birds and insects, while mammals and natural elements such as wind or water occupy the middle and lower registers respectively. Spectrograms are reflected in a pool of water to complete the meditative feeling of communing with nature.

For Krause, the moment he assimilated animal calls matched to an orchestral arrangement was profound, hence the title of the show. “The idea that these were proto-symphonies, proto-orchestrations was eye-opening to me,” he told Artnet News. “If you look at a score by [classical musician Pierre] Boulez, for example, doesn’t look much different from continuous spectrograms of exposure, especially where the habitat is healthy.

However, as the exhibit lights up again and again, not all of the world’s habitats are healthy. The reason for this has to do with another term coined by Krause: anthropophony. Human encroachment has resulted in a dramatic loss of animals in the wild, and thus a sharp decline in their corresponding sounds on Krause’s recordings.

A display showing biophonies in various parts of the world. Courtesy of Exploratorium.

Naturally, this has been unsettling for Krause, who interprets the few remaining animal sounds on his recordings as a cry for help. “We are doing our best to help them,” he explained. “One of the reasons I work with the art world is that if I write a scientific paper and it gets published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, where I had one published last month, six people are going to read it. In the seven or eight rooms where ‘The Great Animal Orchestra’ has been exhibited so far, a million and a half people have seen it.

Krause has always been interested in sound; very early, it is in the music that he hears his vocation. In the 1960s, he performed with the Weavers, alongside folk singer and social activist Pete Seeger, and later formed a band called Beaver and Krause. The duo helped introduce the Moog synthesizer to pop music of the day, contributing the machine’s whirring and hissing to songs by The Doors and The Monkees. Then even they came out with an album, In a wild sanctuarywhich incorporated Krause’s early efforts to record soundscapes.

But, Krause laments, “When I was working in the music business, I was always in closed rooms without any windows. I never saw the outside, and that made me really depressed, and also quite sick. So he turned to Hollywood, producing soundtracks for big movies like 1979. Revelation now. This too turned out to be a disappointment. He said he and others were hired and fired by the director, Francis Ford Coppola, on several occasions, leading to low morale on set.

Disenchanted with Hollywood, Krause went back to school, got his doctorate. in creative sound arts and entered the field of soundscape ecology, with the goal of species conservation. “It’s hard to be good animals,” he said, “but life demands that of us.”

“The Great Animal Orchestra” by Bernie Krause and United Visual Artists. Courtesy of Exploratorium.

At the heart of Krause’s work is a holistic approach to recording animal vocalizations. That is, in unison rather than in isolation. “One of the things that Bernie does when he builds a sound archive,” said his wife, Katherine, present for the opening of the Exploratorium, “is to try to connect viscerally with the world in which these creatures live – a world we truly will never be fully aware of.

“We need a Rosetta Stone to make that leap,” Krause quipped. “And we are looking for that. I think we’re probably very close. Becoming a philosopher, he continued: “You know, I remember a discussion that I had with [experimental musician] John Cage in 1989. We were talking about animal sounds, which he compared to found art, and he said, “Transformation is the key to life and its expression through art. This is the real mystery of the creative nature.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.