Late every Monday night for three years, beginning in June 1992, the now defunct Pyramid Club on New York’s Avenue A hosted a new play.

Or maybe “acting” is too light, too confined a word – these were theatrical events that blended hysterical drag, punk, soap opera, pathos, song and gore in a way that defied trivial description. One evening, you may come across an absurd adaptation of The scarlet letter supplemented by a cover of the essential disco “You Keep Me Hangin’ On”; on another, a sci-fi show where costumes were constructed from scrap metal and bound with black electrical tape. The whole series was a chameleonic (maybe even shambolic) affair; his only constant was his set.

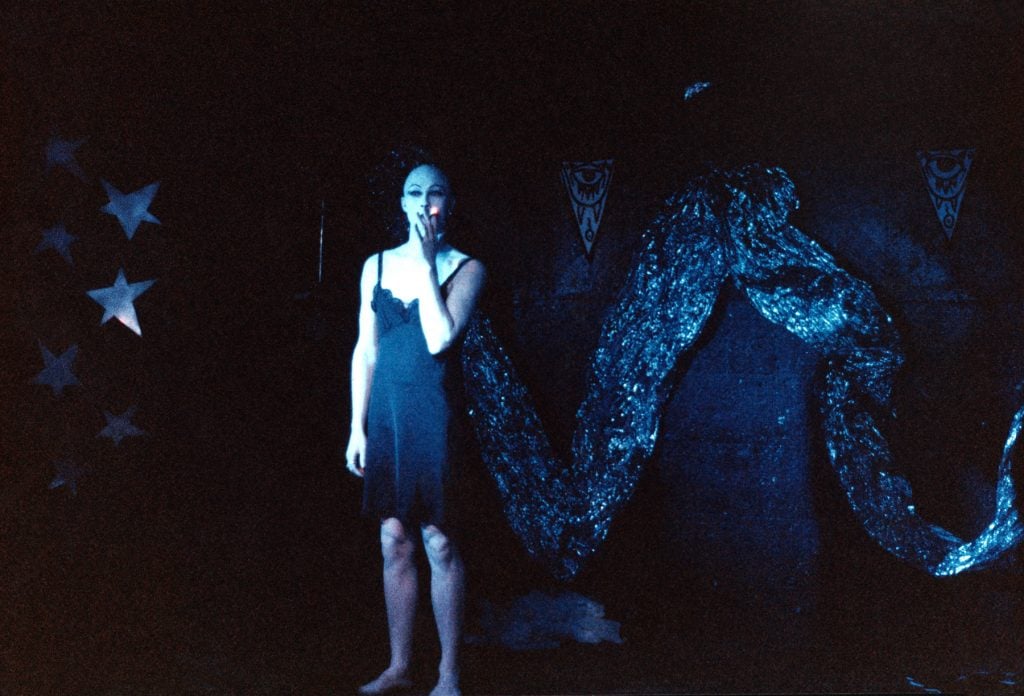

Anohni as Fiona Blue. Photo: Megan Green.

The late-night series was orchestrated by a collective called Blacklips Performance Cult, formed by artists Anohni, Johanna Constantine and Psychotic Eve, who were joined by a cast of 13-20 drag queens, performers, writers and veterans of the night life. . The band never courted publicity (nor did they receive any); instead, more than 120 original pieces supported a singular world on their own.

“We would get together every week to perform these plays that we were writing, and we would mostly perform for each other,” Anohni told Artnet News. “There was a strong component to it that involved witnessing each other… Seeing each other’s dreams, potential, humor, beauty, even suffering. We did that for ourselves and it was really an inside job. We kept it that way until then.

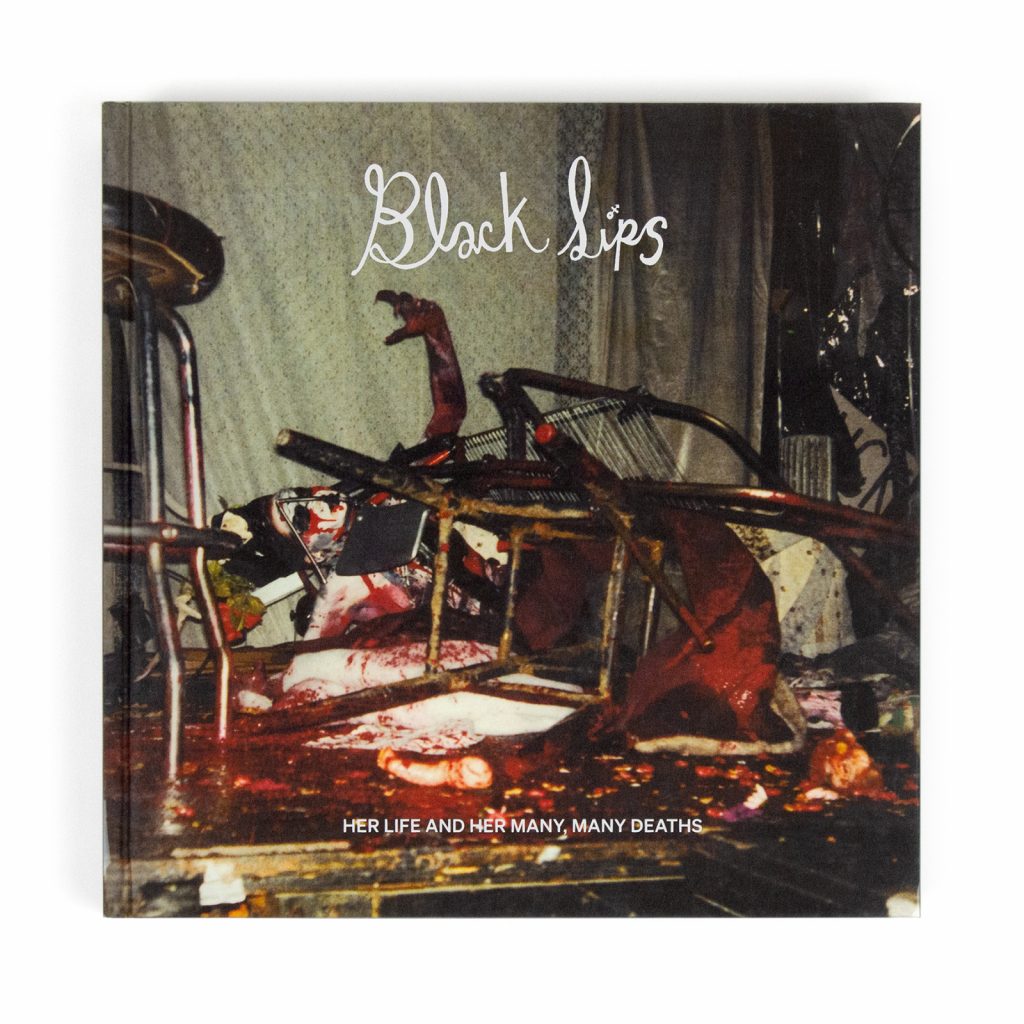

Front cover of Blacklips: His Life and Many, Many Deaths. Photo courtesy of Anthology Editions.

This moment sees the release of Blacklips: His Life and Many, Many Deathsa hard cover (with an accompanying soundtrack) compiled by Anohni and performance artist Marti Wilkerson which documents the troupe’s footprint. Its 471 pages collect scripts, photographs, lyrics, flyers, diary entries, video stills and other ephemera – a full-bleed, color visual feast that recreates the visceral experience of a Blacklips piece.

For Anohni and Wilkerson, putting together the volume was in itself a three-year journey—”an odyssey” for Anohni, “like excavating a ruin” for Wilkerson—whose time had come.

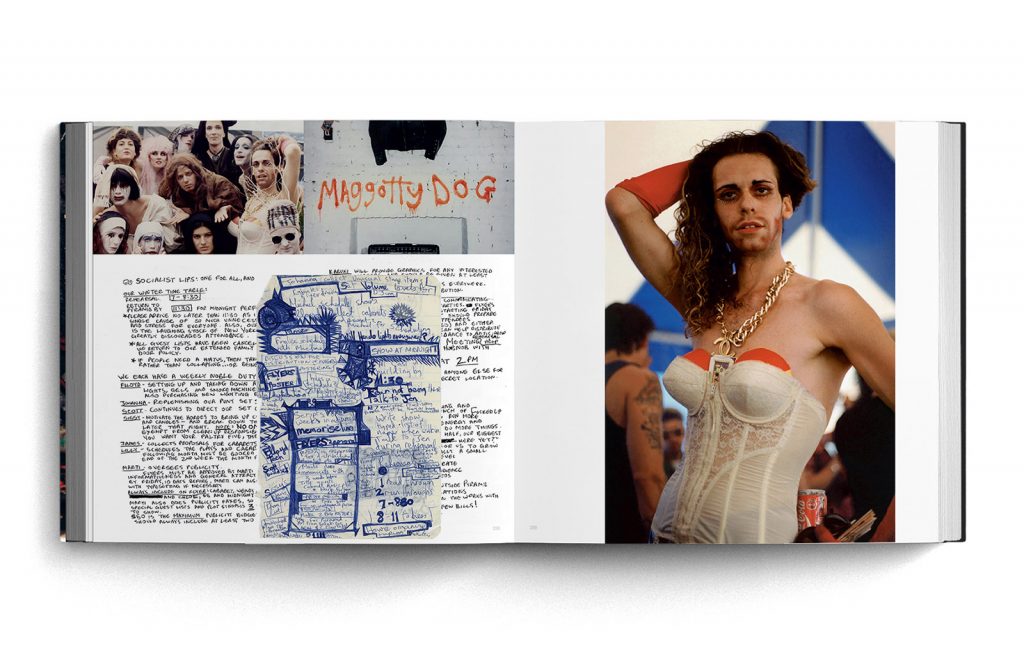

Inside Blacklips: His Life and Many, Many Deaths. Photo courtesy of Anthology Editions.

“It was time to make the effort; it was necessary to represent the band before more of us joined The Away Team,” Wilkerson, also a member of Blacklips, told Artnet News. “The idea of the self-author was an opportunity. Almost everything in the book comes directly from the members of Blacklips themselves; most of the non-dissertation text is our own writing or scripts we typed.

She added: “All the physicality and rigor of the band is on display. We dismissed explanations.

Inside of Blacklips: His Life and Many, Many Deaths. Photo courtesy of Anthology Editions.

In fact, the book’s only concession to exposition is in its pair of introductory essays by Lia Gangitano and Benjamin Titera, with contributions from former Blacklips students. The lyrics explain the group’s emergence in a city that has failed to cope with the AIDS crisis, in a nation that has silenced its gay citizens (transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson was found dead in a street on July 6, 1992) – thus the birth of Blacklips, Titera wrote, “in the midst of collapse and destruction”.

That the collective had to respond to such a landscape with experimental theater served as both catharsis and critique – a creative gesture provocative of “post-everything gender mutants”, according to Anohni, in the face of a culture of cis-sexism. .

Johanna Constantine. Photo: Paul Brisman.

of Constantine world of monsters, for its part, bottled a “rage against a dark future,” set in the midst of a dystopian civilization populated by “demonic characters struggling to maintain the world’s quotas of suffering.” Anohni’s reimagining The scarlet letter recasts Hawthorne’s indictment against Puritanism to ridicule 20th-century Christian America, with the refrain: “In the eyes of your trouser snake, we are all Hester Prynne!”

“He had a weirdly glamorous, anything goes, limitless quality to him,” Wilkerson recalled of Blacklips’ run. “It was almost as if the pyramid itself was a mermaid attracting and beckoning all kinds of adventurers.”

Sparkle and love forever. Photo: Anohni.

Indeed, Blacklips was personal for his creations, especially since a number of pieces were poignant and autobiographical. The memories collected in the book say as much (Sissy Fitt: “Sometimes I have the impression that my life ended in 1995”); Anohni herself referred to “an energetic and densely creative time for a group of us in Manhattan”.

“Making the book, especially sitting with the primary materials in this way,” she said, “changed my sense of what Blacklips was.”

Given the personal and fringe nature of the project, it’s easy to classify Blacklips as a subcultural concern, or in Wilkerson’s words, “That band was super dark.” But just as the collective operated in the niche carved out by Nomi Klaus, John Waters, Jack Smith and Candy Darling, it has also expanded the space for radical queer expression – and quite possibly continues to do so.

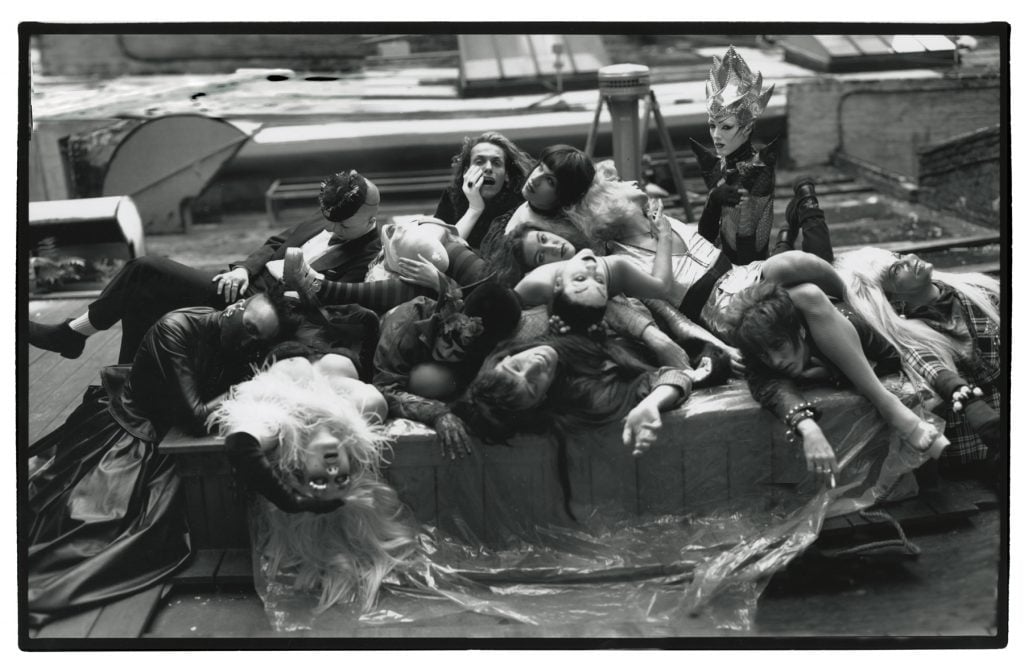

Black lips. Pictured: Michael James O’Brien.

Anohni does not see the publication of black lips like putting an end to the troop. She pointed out that its members, such as Lambert Moss, Kabuki Starshine, Michael Cavadias and Constantine, continue to create (as Anohni herself), ensuring that Blacklips’ legacy remains “a living, becoming thing”.

And if nothing else, she added, “I’m sure we occupy a damp little corner in the grand scheme of things.”

“Maybe with the release of the book and the record,” Wilkerson replied, “we’ll find a drier place.”

Blacklips: His Life and Many, Many Deaths is available on Anthology editions.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.