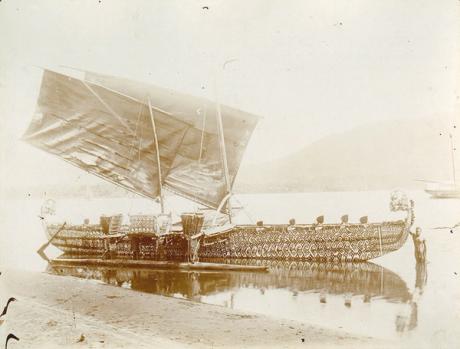

The beautiful boat from Götz Aly’s disturbingly short book (first published in German in May 2021) is an elaborately decorated 50-foot sailing canoe made on the island of Luf, which is part of the Hermit Islands in the Bismarck Archipelago, off the northwest corner of what was then German New Guinea (now part of Papua New Guinea). In 1882, German colonizers burned down houses, boats and trees and turned the island into a coconut plantation. In 1890, the newly built boat was shipped to Germany, where it ended up in the Berlin Ethnological Museum.

In 2018, the ship painted with decorative carvings was lowered into the central hall of the new Humboldt Forum, Berlin’s non-Western art museum. As we follow the ship’s journey there, we learn how its acquisition helped destroy a local South Seas culture and most of that culture’s treasured artifacts. Aly says his subject is “the cruelty, ignorance, fear and greed of German settlers in the South Seas”, an area so far overshadowed by German colonial crimes in Africa.

Plunder in the South Seas

Aly’s detailed account follows German ships as they arrive on Luf Island to punish local people for an earlier fight with the Germans, burning homes and forests, stealing food and clearing land for plantations. of coconuts where the remaining islanders were enslaved. What was not destroyed was plundered. The German attackers stole all the items they wanted.

A respected German historian of the Nazi era and of European anti-Semitism, Aly is in new territory here. It draws heavily on official documents and accounts where Germans wrote openly about violence in the South Seas. He also had inside information. His great-great-uncle was a German navy pastor.

The mission throughout German New Guinea was clear. Navy ships ensured safe conditions for trade and agriculture. “This situation follows a truism in European colonial history,” writes Aly. “Flag follows trade.” The consensus among the Germans was that these actions would eventually wipe out the indigenous “people of nature” population who lacked a written language and a sense of their own history. Sometimes the Germans paid for local carved objects in beads, tobacco and mirrors that cost pennies. A special term, “anonymous purchase”, referred to small items the Germans left behind when the local population fled the naval patrols that looted the settlements.

The German museums that hoped to receive them were convinced that colonization would eventually eradicate the populations that produced these works. Therefore, writes Aly, the pressure to collect was great. Obviously, if trade was at one end of the looting chain, German museums were at the other. Officials competed to amass collections from the South Seas, most of which were eventually sold to museums that fought over artifacts and body parts.

Crucial in this process was the role of the emerging discipline of ethnology. Important German collectors of South Seas objects included ship’s doctors, many of whom moved on to the new profession. This field, active in universities and museums in late 19th and early 20th century Germany, increased the demand for works by “peoples of nature”. At that time, a common ethnological theory held that the colonized local people died, not because of disease and the destruction of their livelihoods, but because they had willed their own extinction.

All the more reason to ship the Luf Boat to Germany, writes Aly. In a careful description, quoted from the writings of Felix von Luschau, the Berlin curator who acquired the boat (and the Benin bronzes), we learn of the vessel’s beauty and its simple but refined design, without a single nail, which has allowed the ocean to travel long distances with and against the wind. The Germans targeted all native boats in regular punitive expeditions intended to destroy local economies. The Luf Boat is the last existing vessel of this type.

While the boat is still displayed prominently, the museum’s website notes gaps in its provenance and cites contacts with Papua New Guinea. Another time, another manners? “The men who ran German museums knew only too well the atrocities that were unfolding,” says Aly, who cites the account of a local man who was cut and wrapped for transport to Germany right after his execution.

His book ends with a courteously unofficial response letter from GLOBAL. Human Arts. Heritage, an imaginary encyclopedic museum in Port Moresby, New Guinea, to an imaginary German claim to Western spoils of war there. The object is the world’s only surviving sculpture by Tilman Riemenschneider, and the museum’s response is “no, but come visit”. The parody sheds light on a dark story.

• Götz Aly, translated by Jefferson Chase, The Magnificent Ship: The Colonial Flight of a South Seas Cultural TreasureBelknap/Harvard University Press, 224pp, 36 illustrations, US/UK $29.95/£29.95/€27.95 (hb), published March 31

• David D’Arcy is corresponding for The arts journal At New York