In 1947, Italian-born architect and designer Lina Bo Bardi fled the ruins of post-World War II Europe and resettled in São Paulo. She built her home, a glass-walled box floating atop slender columns, on a mostly barren slope in what was then far from the city center.

Today, Casa de Vidro, as it is now known, overlooks a lush tropical terraced garden in one of the most invigorating neighborhoods in South America’s largest metropolis. On May 24, a small group of guests gathered there to inaugurate “The Square” exhibition, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Bottega Veneta in Brazil. It was also the kickoff and cornerstone of São Paulo Fashion Week, which filled event spaces across the city.

The exhibition fades into the personal universe of the architect Lina Bo Bardi. Courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

Previous editions of “The Square”, in Dubai and Tokyo, have brought together local artists for exhibitions, screenings and new performances in custom-built environments. The São Paulo edition, on the other hand, relied heavily on Bo Bardi’s legacy. The architect, who would spend the rest of her life in Brazil, became the country’s leading proponent of a modernist style that incorporated vernacular design elements from the region, which she often applied to socially conscious projects like housing. social or museums. His own house, House of Vidrois now a museum.

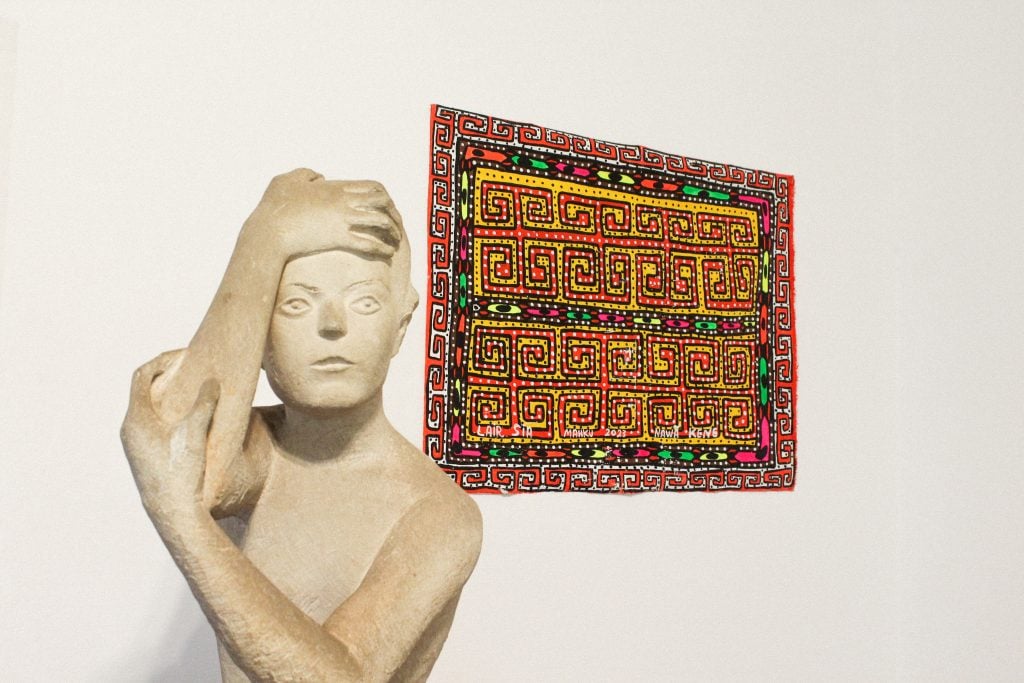

One of Ibã Huni Kuin’s vibrant works is displayed in the background of this installation view of “The Square”. Courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

Curated by Rio de Janeiro-based curator and photographer Mari Stockler, “The Square” showcased a wide range of contemporary and historical Brazilian artists that Bo Bardi could presumably have collected if she were alive today. Their work has been subtly incorporated into Bo Bardi’s collection of indigenous and Afro-Brazilian art permanently housed at Casa de Vidro. It was sometimes difficult to tell which works were new and which belonged to the architect. Some of these inclusions were so seamless that a first-time visitor to the house might not have noticed that an exhibit was on display. “It’s intentional,” Stockler said.

Visitors were invited to follow “paths” through the house organized around three themes – geometry and spirituality, tropicalia and music – although it would be impossible to glean them without the aid of maps in a four-volume catalog of accompaniment, and most participants roamed freely, sipping cocktails as they sailed.

Luiz Zerbini, Untitled (2009) and Andy Villela, Araujolândia (2021). Courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

Under a prominent overhang on the first floor, a painting of Ibã Huni Kuin, a master of the Huni Kuin people in the Brazilian Amazon, was on display near a carved wooden canoe that Bo Bardi had acquired in the area. Its colorful jungle flora and fauna, displayed in the open, was reminiscent of the vibrant Huni Kuin paintings currently on display. in an investigation a few kilometers away Sao Paulo Art Museum, the monumental museum also of Bo Bardi’s design. The work slightly resembled Araujolandia (2021), a painting by young Brazilian artist Andy Villela; its semi-abstract rendering of hanging potted plants and a blue tiled floor, meanwhile, was reminiscent of the interior of the house upstairs.

Fernanda Gomes, Untitled (necklace) (2016). Courtesy of Bottega Veneta

There, Luiz Zerbini’s untitled 2009 composition of color-coded projector slides resembled modernist works by Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape, but in a medium that Bo Bardi often used in his architectural practice. Fernanda Gomes Untitled (necklace) (2016), a pair of white gold spoons tied together by a length of string, rested discreetly on the blue marble dining table, where they seemed like a natural appendage for the silver Art Nouveau punch bowl that sits permanently in its center.

Fanciful animal-shaped assemblages of sprouting tubers by Cristiano Leinhardt (Treat a species, 2014) humorously perched on pewter kitchen worktops, like food returning to nature. Other works that Bo Bardi would almost certainly have collected had they been available to him during his lifetime: a painting by the late artist and environmental activist Hélio Melo, O amanhecer no syringeoffers a dreamlike and surreal vision of dawn in the tropical forest, completely in line with the imagination of the architect.

An undated interior view of the Casa de Vidro. Courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

Throughout the lounge, books on modernist and indigenous Brazilian art were stacked or open on original furniture of Bo Bardi’s design, or beside replicas for visitors to sit and read. “When you see pictures of the house from Lina’s time, there are books everywhere,” Stockler said. “I wanted to make sure the house was inhabited.”

Bo Bardi’s drawing board is in the foreground. Courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

This approach extended to the architect’s drawing board, where a construction helmet with the logo of SESC Pompeia – a vast Bo Bardi cultural complex designed for an underprivileged district of São Paulo – stood alongside poems and works on paper of some of its friends, such as Hélio Oiticica. One could imagine that they had been left there when Bo Bardi died in 1992.

Bottega Veneta’s interest in Casa de Vidro is easy to understand. Like Bo Bardi, the Italian fashion house is known for its subtle, intricately crafted details. But aside from the beautifully printed catalog — almost cubic in size, to befit the show’s title — and a few woven leather bags that some of the attendees chose to carry, Bottega’s presence at the event was relatively minimal.

Curator Mari Stockler and Bottega Veneta creative director Matthieu Blazy. Courtesy of Bottega Veneta.

At Casa de Vidro, the focus was on the performers, who would mingle for hours, chatting in the dappled autumn sun. Despite the glamorous looks and the occasion, it sometimes seemed like Bo Bardi herself – a hostess renowned for her generosity – had called them there.

“Casa de Vidro is one of my favorite places,” said creative director Matthieu Blazy, who was on hand for the event. “With ‘The Square São Paulo’, we recognize how Lina’s ideas and aesthetics resonate to this day, always reminding us of the transformative power of design and culture.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: