At a recent exhibition of digital art by Jake Elwes at Gazelli Art House in London, not every exhibit was in working order.

Digital Whispers, programmed in 2016 to pick up live tweets within a two mile radius and “whisper” them via an attached speaker, stopped working in April, after Twitter cut-off access to its free API and removed the option to filter tweets by location. Forced to adapt to the new circumstances, Elwes simulated the original work by playing a recording from 2019 on loop, and retired the ongoing work by cutting off its date range at 2023.

Elwes is not alone in facing the challenges new media art presents to conservation efforts. While there are entire museum departments concentrated on repairing medieval tapestries and examining the craquelure of 19th century paintings to preserve their lifespan, the comparatively nascent field of new media art conservation needs to take urgent action if it hopes to save valuable contemporary artworks from the accelerating pace of technological transformation.

If a digital artist hopes that their work will outlive them, the work must be continually monitored and adapted to run as extinct hardware, outdated software, and other factors threaten the work’s lifespan at an ever-quickening clip. In recent years, wider shifts in the centralized ownership of technology and factors like hype cycles and planned obsolescence have presented new challenges to the field, and preserving new media art has now become far more complex than just shopping eBay to find a working VCR to play a Nam June Paik video tape.

Jake Elwes, Digital Whispers (2016-2023). Image courtesy of Gazelli Art House.

The question of how an artwork would be best conserved usually depends on what made it art in the first place. Sometimes, a concept is the key element that must be preserved. Julia Scher’s Predictive Engineering (1993-) is a complex site-specific installation that simulates uncomfortable experiences of security and surveillance for the viewer. It is re-engineered each time it shows at SFMoMA so that the equipment still feels unsettling rather than like an outdated artifact.

In other cases, the ancient hardware is an integral part of the form and character, as was the case for Gary Hill’s Tall Ships (1992), a video installation recently restored by Small Data Industries, a specialist lab founded in New York by Cass Fino-Radin.

“We went to great lengths to ensure that if you saw it at Documenta in 1992, and you saw it now, you wouldn’t know anything had changed at all,” they told Artnet News. “Behind the scenes, everything has changed. We migrated the work from playing off 16 LaserDisc players and a kooky old P.C. It’s incredibly modernized now.”

Digital conservation. Photo by Matthieu Vlaminck and Morgan Stricot, courtesy of ZKM.

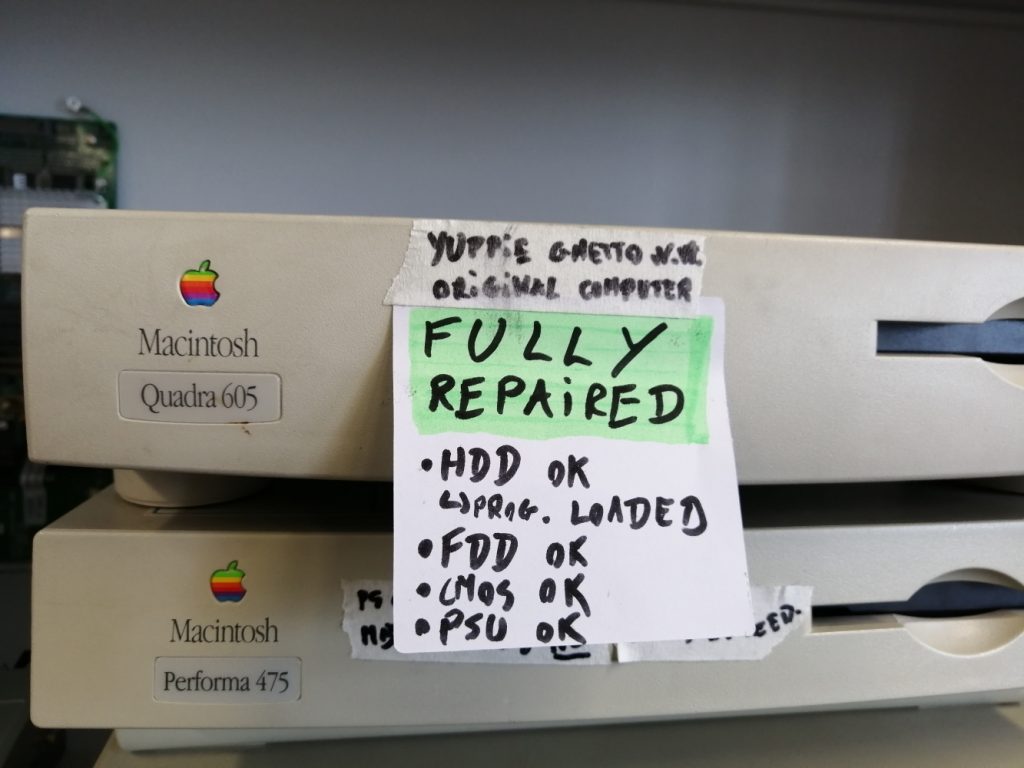

But rapid shifts in technology, alongside the centralization of the industry has brought with it new challenges. Thirty years ago, “the web was a wild and unstandardized place,” said Fino-Radin, and media art was innately fragile. The flip side was that hardware could be pulled apart and tinkered with, and they described “figuring out how it works, reverse engineering it, documenting it, and forming a new approach,” as a satisfying challenge.

Today, “the reason hardware has stopped working isn’t because it’s broken per se, it’s because some kind of obsolescence has been introduced by the corporation that made it.” The same is true of software, which can have its license expire, be dependent on other outdated softwares, or suddenly introduce a subscription fee.

“We have less trouble with the ’90s artworks than today’s,” agreed Morgan Stricot, head of digital conservation at the ZKM Karlsruhe, a leading centre for media and technology in Germany. Nowadays, “it’s all closed, you can’t open or change anything,” and companies don’t provide comprehensive manuals, a problem that has ignited the “right to repair” and “iFixit” movements.

Agnes Hegedüs, Memory Theatre VR (1997). Photo courtesy of ZKM, © Agnes Hegedüs.

This often means more invasive conservation is required, including rewriting the artwork from scratch in a new programming language. “This is the last resort,” said Stricot. “It comes with a lot of ethical issues. How do we judge that it is not conjecture? What we do is intervene while the artwork is still running, so that we can compare both iterations.”

The urgency of the question is such that conservation concerns often enter into the conversation at point of sale. Gazelli Art House’s founder Mila Askarova said that the gallery has facilitated digital art sales with a guarantee that the artist would update the work if necessary, a clause that did not influence pricing.

Askarova pointed out that in the nascent digital art space, galleries and artists rely on maintaining relationships with collectors, and updating artworks to ensure their long-term survival. “If we can help, we obviously will,” Askarova said. Nonetheless, “as a gallery, we don’t want to become a troubleshooting call centre.”

A screenshot of the 2019 version of Tristan Schulze’s SKIN 3.0. Image courtesy of ZKM.

A screenshot of the 2021 version of Tristan Schulze’s SKIN 3.0. Image courtesy of ZKM.

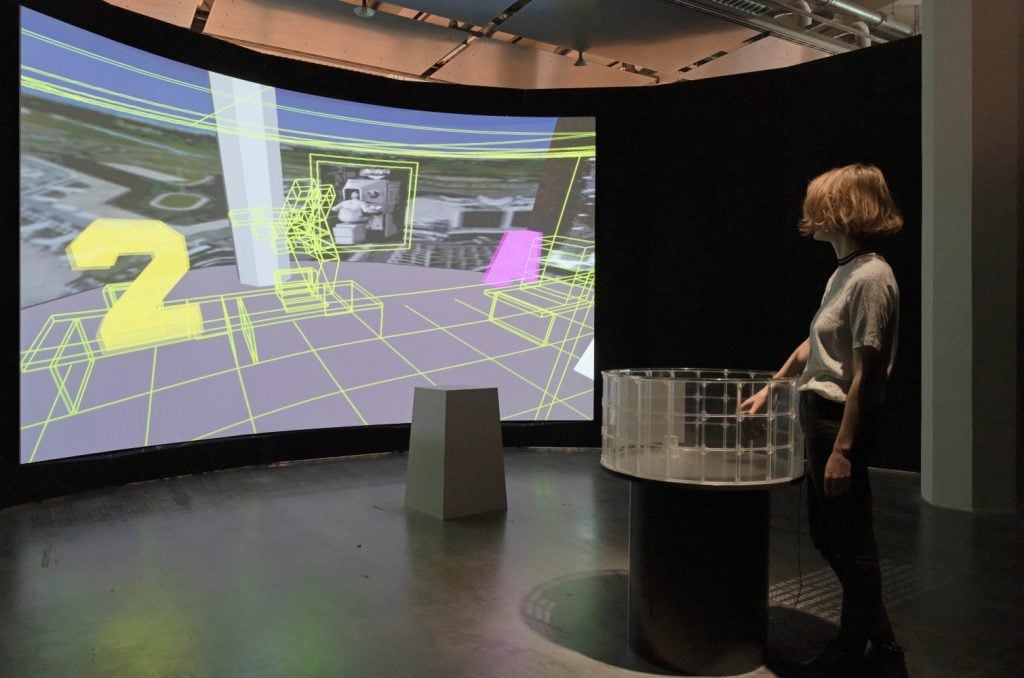

Virtual reality, which has become highly popular in museum exhibitions, is a particular cause for concern. V.R. glasses can expire just a few months after acquisition, as the necessary firmware falls out of date. Two examples at the ZKM demonstrate what is at stake. Memory Theatre VR (1997) by Agnes Hegedüs allows users to navigate a tiny model using a mouse and was made on a powerful SGI computer. No equivalent exists today, so Stricot’s team are extracting the work’s 3D models and rebuilding them on a Windows 10, carefully retaining the original ’90s aesthetics and adjusting the speed to mimic slower processing times.

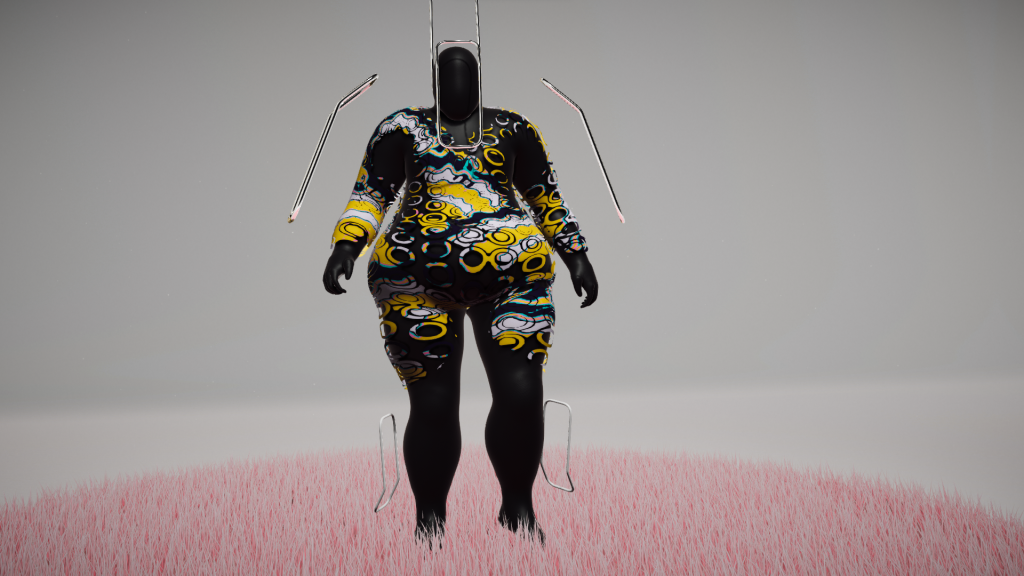

By contrast, the 2021 version of another V.R. work that had to be rewritten, Tristan Schulze’s SKIN 3.0, which was made using the Unity game engine, is noticeably different than the 2019 original. “Each time we migrate it, we will get a better result,” said Stricot. “There’s going to be a loss for historicity. This artwork will never be a representation of 2019 aesthetics in ten years, it will always be new and shiny.” If all VR ends up on the same hardware, there may be few obvious differences between works from 2020 or 2040, further undermining any curator’s attempt to impose an art historical narrative.

“We need help from industry,” said Stricot, who noted that Unity just made a long-term supported version of its engine. “This tells us they care about the artists using their software.”

“Artists are usually trying to hijack a technology, or push it a bit,” noted Stricot. “So it breaks faster than it would with normal use.” Museums with an established best practice must also support their international colleagues’ early forays into collecting digital art, so that expertise doesn’t remain concentrated in the U.S., the U.K., Switzerland, and Germany. “Artists need to be able to support themselves by selling work, so we shouldn’t be afraid,” Stricot added. “We should just be aware that its going to take more energy than collecting a painting or sculpture.”

Installation view of Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018–2019) in “WORLDBUILDING” exhibition at JSF Düsseldorf. Photo: Alwin Lay.

To lengthen technology’s dwindling lifespan, major collections require extensive documentation from artists as well as source code and a stockpile of spare parts. The Julia Stoschek Foundation in Düsseldorf, Germany, which owns one of the most important collections of time-based media, has artists fill out a 30-page questionnaire so that its conservation approach can be tailored to each artwork.

When the foundation collected Ian Cheng’s computer-based artificial lifeform known as BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018-19), it came with extensive documentation specifying the use of macOS Mojave version 10.14, which is already outdated. “From the beginning we knew there could be problems updating the iMac, so we froze it and bought spare computers from the same manufacturing period,” said conservator Andreas Weisser. Meanwhile, the I.T. engineer is testing a virtual machine that should be able to simulate Apple’s old operating systems.

As conservation of digital media grows more complex and labor intensive, costs can easily rise to tens of thousands of dollars. “Before an artwork enters the collection, we have to discuss whether its possible to keep it running,” said Weisser. “The decision is not made by me, however I can highlight pain points and question the long-term implications, saying, it works perfectly now, but what about in ten years?”

Increasingly, artists are also exploring A.I., but most often via simplified interfaces or code libraries. It takes a machine learning specialist to really delve into the complex algorithms beneath this high-level layer, so conservators may also struggle to update the source code if anything goes wrong.

But some artists argue that there needn’t always be an easy solution. Because many are experimenting with emerging tech, they don’t always want works adapted to a new medium. British artist Anna Ridler welcomes the temporality of her art, and a 2018 version of Mosaic Virus, in which a tulip shape shifts in response to the fluctuating price of bitcoin, no longer runs but survives via an MP4 recording. “There’s an assumption that things live forever on the internet, but they absolutely don’t,” Ridler said. “I’m very inspired by land artists who know what they are creating is finite.”

More Trending Stories:

The Company Behind the Wildly Popular ‘Immersive Van Gogh’ Experience Has Filed for Bankruptcy

Drake Outs Himself as Buyer of Tupac Shakur’s Iconic Crown Ring, Sold for $1 Million at Sotheby’s

Fast-Rising Artist Jeanine Brito’s Visceral Paintings Put a ‘Dark and Grotesque’ Spin on Fairy Tales

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: