Naples and Paris share a turbulent history, linked by Catholicism, pastry and a centuries-old art exchange—and fractured by conflict and Napoleonic occupation. Its major arts institutions, however, get along wonderfully.

THE Capodimonte Museum just sent 70 Renaissance masterpieces to get acquainted with their period counterparts in the Louvre collection. It’s a six-month show, the opening of which saw the French and Italian presidents present, and the director of the Louvre, Laurence des Cars, happily declare “it’s the Neapolitan season”.

“Naples in Paris”, which will run until January 24, 2024, is billed as the largest exhibition ever dedicated to the Italian Renaissance. It might be, and while size isn’t everything, it’s a well-organized affair. All the great Italian painters are present and counted—MichelangeloMassacio, Raphael Caravaggio, Bellini, TitianArtemisia Gentileschi and more – with Capodimonte filling in the gaps in the Louvre’s invaluable collection (since the 17th-century Kings Louis III and XIV of France preferred the Venetian and Roman schools to the Neapolitan).

Caravaggio, The Flagellation (1607). Image: courtesy Capodimonte.

It is a remarkable and rare collaboration between two vast European museums. However, with the former royal palace of the Bourbons undergoing major renovations until 2024, “Naples in Paris” was born more of pragmatism than brotherly love.

Sylvain Bellengerdirector of Capodimonte, also hopes to associate with the greatest famous museum could draw attention to the Naples institution. “Many visitors are already familiar with some of the masterpieces of the Capodimonte collection,” Bellenger said in a statement, but the museum is “still unknown to the general public” since most tourists go to Pompeii and Herculaneum instead. Maybe this big release will do.

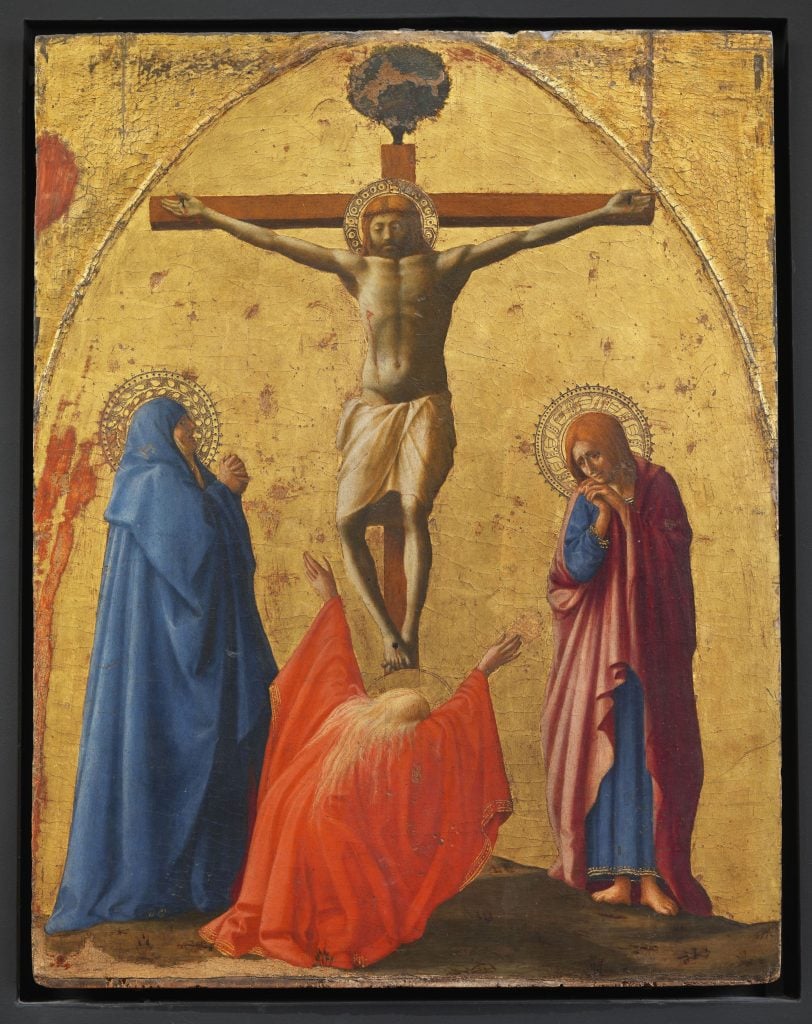

Massacre, The Crucifixion (1426). Courtesy of Capodimonte

The exhibition is spread over three distinct spaces inside the former seat of the French monarchy. The Grand Gallery, as its name suggests, makes the biggest statement. Thirty-one paintings by Capodimonte are intertwined with Louvre works by Titian, Caravaggio and Guido Reni. The stars are those of Massacio The crucifixion, a work backed in gleaming gold that brings the viewer to the level of Mary Magdalene, who passes out at Jesus’ feet with her hands twisted. Differently captivating is Parmigianino’s Portrait of a young woman, a figure who, by her dress, her pose and her gaze, seems of indeterminate age. For Bellenger, she is a figure we recognize, although we may not know in which museum she lives.

In the Clock Room, institutions turn to drawing, or caricature, of which Capodimonte has more than 30,000. The most famous here were inherited from Fulvio Orsini including Raphael Moses before the burning bush, a charcoal work without flame and full expression, with the prophet crouching and calm in the presence of his lord. Another is Michelangelo preparatory cartoon for the Vatican group of soldiers, exhibiting intricate armor work and a quiet intimacy rarely associated with 16th century military. The Louvre, in response, offered works by Raphael and his pupil Giulio Romano.

Michelangelo, group of soldiers (1546–50). Image: courtesy Capodimonte.

The Chapel Room takes on a larger dimension, featuring a mixture of Neapolitan marvels: a El Greco and a Titian here, a miniature sculpture by Filippo Tagliolini and a gilded silver and crystal casket there. It is a space that shows all the diversity of the Capodimonte collection, largely thanks to its Farnese and Bourbon families.

The two museums “are symbols of the historic ties between France and Italy,” des Cars said in a statement. “This exceptional and unprecedented partnership perfectly illustrates my vision of the future role of the Louvre in Europe and museums.”

See more images from “Naples in Paris” here:

Raphael, Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514–15). Image: courtesy of the Louvre.

Parmigianino, Portrait of a young woman (Also known as Antea, circa 1535). Image: courtesy Capodimonte.

Annibale Carracci, Pieta with Saint Francis and Saint Mary Magdalene (1600–25). Image: courtesy of the Louvre.

Annibale Carracci, Pieta (1599-1600). Image: courtesy Capodimonte.

Correggio, Venus and Cupid with a Satyr (1524-1527). Image: courtesy of the Louvre.

Titian, Danae (1544-1545). Images: Capodimonte.

Jose de Ribera, club foot (1642). Image: courtesy of the Louvre.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith killing Holofernes (c. 1612–13). Image: Capodimonte.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.