We may never know exactly how much paintings Creation of Elisabetta Sirani. It’s not because his baroque altarpieces, portraits and paintings of legendary heroines weren’t cherished – during his lifetime, patrons demanded his works, commissioned them and collected them (despite his high prices). And it’s not because Sirani was a messy archivist either. The Italian painter kept a detailed work diary, published shortly after her death.

As the only known workbook for a woman artist in the 16th or 17th centuries, Sirani’s diary listing the 203 paintings and two prints she made for 100 different patrons is a rare record. She also wrote about the subject of each painting and how she developed her concepts and compositions, giving unique insight into her working process.

Yet we may never know exactly how many paintings La Sirana (as she was nicknamed) devoted to the canvas, as she made many in secret. According to his biographer and close family friend, Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Sirani was the breadwinner of his family’s workshop (after his father contracted gout) but his father managed his income. As a workaround, Sirani painted artworks he didn’t know about and left them out of his workbook, which means his oeuvre is even bigger than the 205 artworks he does. she recorded during her short decade-long career.

Elisabetta Sirani, allegory of painting (possibly a self-portrait, 1658), oil on canvas. Photo: © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

“She often offered [these secret] function as thank-you pieces for commissions,” says Adelina Modesti, Sirani Scholar and Honorary Fellow in Art History at the University of Melbourne. “She was also using them as a barter for necessities and medicine without her father’s knowledge.”

An attempt to see a fuller inventory of Sirani’s career than the version she left in writing comes in the form of a biography published this month, Elisabetta Sirani (Lund Humphries, Jun 2023) written by Modesti. It is the first book in English with a comprehensive overview of the work of Sirani, whose legacy was celebrated after his death but increasingly overlooked when the Bolognese school fell out of favor.

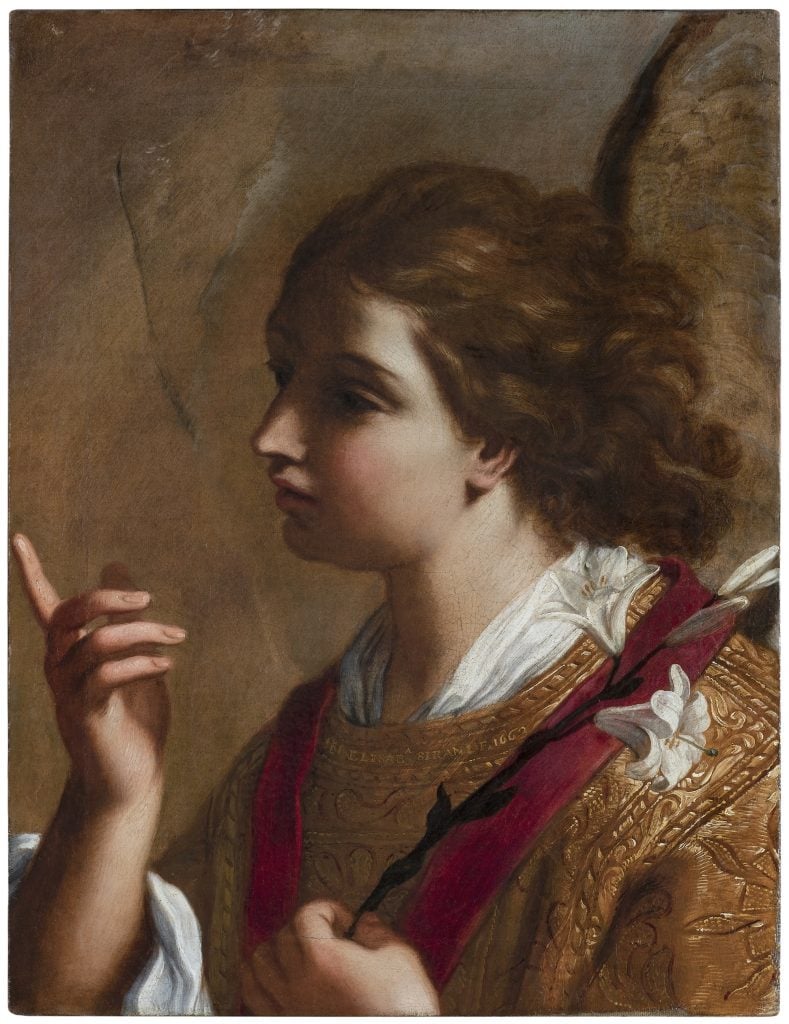

Academic interest in her has seen a revival since the feminist wave of the 1970s, and in 2018 she had a personal exhibition at the Uffizi Galleries. This biography features unpublished works by Sirani, including The Virgin announces (1658) and The Angel of the Annunciation (1663), both of which have recently appeared on the art market.

Elisabetta Sirani, The Angel of the Annunciation (1663), oil on canvas. Photo: Private collection in Bologna, since 1930.

Telling Sirani’s story from the beginning, the biography features her father, artist, dealer and life drawing teacher Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who trained Elisabetta and her two younger sisters, Barbara and Anna. Giovanni provided Sirani with a comprehensive humanist education which included technical and theoretical artistic training and access to his large library of classical and religious books.

She began working as a freelance painter at the age of 17, and at 24, when her father’s health deteriorated, she began to run the family workshop (where her sisters also worked). She is also believed to have taught female artists, creating a new model of female-led art education at a time when women were trained by their fathers or other men in their orbit.

“Her teaching and success proved hugely influential on subsequent generations of Bolognese artists. She never married (although it is unclear whether this was by choice or circumstance), pursuing a career in the arts rather than in marriage and procreation, thus representing a new social category of femininity – the single professional woman,” Modesti shares. “She was also the first female artist to be positively compared to male artists by her contemporaries.”

Bologna was particularly encouraging for female artists, and Sirani is said to have been aware of local role models such as sculptress Properzia de’Rossi, painter Lavinia Fontana, and religious artist Caterina Vigri. She built on their legacy and propelled it by painting primarily classic and biblical narratives (considered more complex than still lifes and portraits which many consider appropriate genres for women).

Elisabetta Sirani, Judith with the head of Holofernes (second half of the 17th century), oil on canvas. Photo: Courtesy of the Lakeview Museum of Arts and Sciences.

According to Modesti, Sirani created more history paintings and public works in her short career than any other female painter before her. His first major Bolognese public commission was for an impressive meter five by four Baptism of Christthe largest altarpiece of a woman in the early modern era.

Another genre she was known for was the strong woman, or heroic women (a popular humanist subject of her time). In the 14 paintings Sirani created in this vein, she chose unusual aspects of the stories, some of which had never before been introduced into easel painting. In her Judith Triumphant (1658) for example, which includes a self-portrait of Sirani as the biblical Judith, she did not choose the violent act of beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes as Artemisia Gentileschi did, or alone with her servant and head cut just after the law. Sirani described the moment when Judith returned victorious to her city as her saviour, presenting the head of Holofernes to the people of Bethulia as assurance that she had redeemed them from the invaders.

In other strong woman paint, Timocleia of Thebes (1659), Sirani is inspired by the ancient story of Timoclea who was raped by one of Alexander the Great’s captains. After raping her, he demanded Timoclea’s money and jewelry, and she told them they were hidden in a well in her garden. As he bent down to look inside, she pushed him away and stoned him to death. Tiepolo, painting the story later, illustrated the rape scene. Sirani painted Timoclea at the height of her powers, dynamically throwing the captain headfirst into the well and holding her legs apart. This part of the story had never been painted before Sirani.

Elisabetta Sirani, Timoclée kills the captain of Alexander the Great (1659). Photo: Courtesy of the National Museum of Capodimonte.

Not only did Sirani actively distinguish herself from the way such stories had been painted before, but she also created an individual style different from that of her father. Over time, his female figures became less idealized and more natural, painted in broad brushstrokes and bright colors. Ultimately, his work was more popular than his father’s, garnering higher awards.

When rumors started circulating that Sirani’s father had painted her works but she had signed them to make them more marketable (being considered more special from a woman’s hand), she usually started painting in front of a public. Becoming something of a Bolognese spectacle or tourist attraction, Modesti writes that “everyone who was anyone would go to La Sirana to see her perform” and “would generally be won over by her charming and sometimes ironic wit”.

Sirani was working on commissions for Roman Empress Eleonora Gonzaga and Grand Duchess Vittoria della Rovere when she died a sudden and painful death at the age of 27. Although her father accused the maid of poisoning her, an autopsy revealed that Sirani had ulcers and holes in her stomach and died of natural causes.

Elisabetta Sirani, Portia injuring her thigh (1664), oil on canvas. Photo: Collezioni d’Arte e di Storia della Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio, Bologna.

There was intense and widespread public mourning in Bologna after his death. She was buried next to Guido Reni in the Church of San Domenico, and generally considered the “second Guido”. A few months after her death, she received a civic funeral, an honor usually reserved for politicians and aristocrats. The memorial service was staged theatrically, with the highlight being a life-size sculpted effigy of her painting a canvas.

“She was endowed with a keen intelligence…an excellent memory…a good judgment,” said Sirani’s eulogy, law professor Giovanni Luigi Picinardi. “Perfect knowledge of the science she practiced.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.