Alice Neel has a fascinating and eccentric place in pop culture. A few years ago I did a bunch of research to review his exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum, but you can’t always use all the cool stuff you find. With a great show from Neel draw attention at the Barbican in London, I thought it might be a good time to dig into the curious case of Alice Neel’s presence in the cinema.

Neel cut her teeth working at the WPA in the 1930s, stuck to her idiosyncratic style of realistic painting and leftist philosophy through decades of living in obscurity, and was brought back to prominence when ‘she was championed by feminist artists in the 1970s. Since then, she has been highly regarded.

But here’s what fascinates me: Even at the height of his popularity, in the McCarthyite period after World War II, when Neel’s bohemian ways, Communist affiliationsand the yen for figuration made her persona non grata in the mainstream art world, she was always an irresistible character. In fact, she was such a character that even when her art was almost impossible to show, she herself was still present in the culture – a status that predated her rediscovery by some time.

If you want to see what I mean go watch The big clockthe 1948 film noir classic.

The film is directed by John Farrow (Mia’s father), based on a 1946 crime novel by Kenneth Fearing. character himselfwas considered the ancestor of the genre of “proletarian poetry”, had political sympathies similar to Neel’s, and was steeped in the same New York milieu.

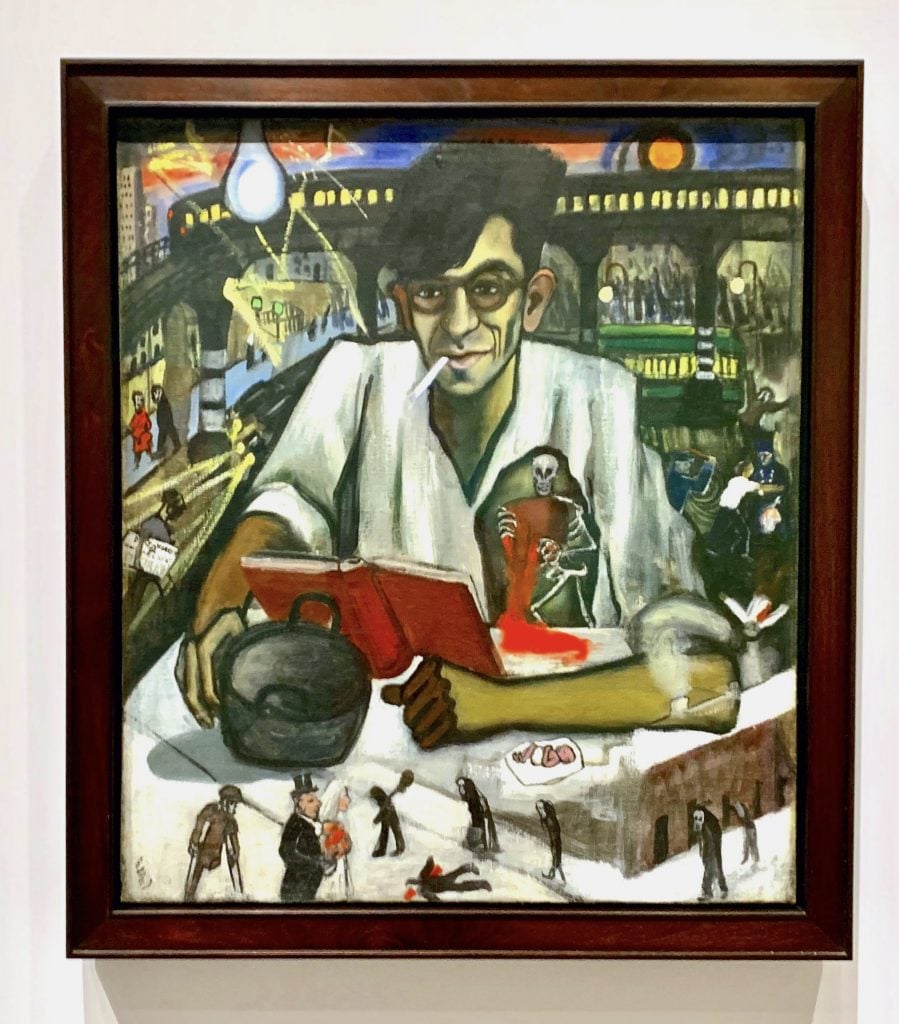

Neel painted Fearing in 1935, in a Symbolist mode, featuring the poet with an open book in front of him and a cigarette in his mouth, beaming at the viewer through thick glasses. All around him, a landscape populated by tiny characters acting on the social injustices of the time. Most notably, Fearing’s chest is opened and a small demon skeleton is shown clutching his heart. He disliked the skeleton when he saw it and told Neel to excise it, although Neel’s intention, she later said, was to show that the “heart of Fearing bled for the sorrow of the world”.

by Alice Neel kenneth fearing (1935) at the Metropolitan Museum. Photo by Ben Davis.

The poet then made the gift of an ambiguous tribute by including the character of “Louise Patterson”, a hard bohemian painter evidently based on Neel, in his novel The big clock. Fearful had worked for six months at Timewhich was part of the Henry Luce media empire, and the plot encoded its criticism of the industry, involving mogul Earl Janoth of Janoth’s fictional media empire killing his mistress, then covering her up.

The big twist is that the mogul gets his underling George Stroud, editor of Paths of Crime magazine, to lead the effort to track down the other man his mistress was with on the night of his murder, to assign the murder to her – unaware that this other man is Stroud himself. The satisfyingly knotted story therefore ends with Stroud both conducting an investigation and trying to sabotage it from the inside.

When cultural historians speak of a submerged Marxism in the black genre, and how the indirect subject of black is often anti-communist panic, The big clock is a star exhibit – it’s a perverted witch hunt, designed by an industrialist. (The story was remade as the Reagan-era Kevin Costner spy thriller No Exitwhile the film’s climax amidst the huge clockwork atop the Janoth skyscraper inspired the decor of the clock tower of the Coen brothers The Hudsucker Proxy.)

poster for The Great Clock. Left to right: Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, 1948. (Photo by LMPC via Getty Images)

In Fearing’s novel, Patterson’s character comes into play because Stroud had bought him a painting at a thrift store the night of the crime; the artist had encountered it while buying it – she had tried to buy back her own painting herself – and her ability to identify it made it important for the hunt.

Fearing describes Patterson’s style of figurative painting as having qualities of “simplified abstraction and new intensifications of color” that aptly describe Neel’s gaze. More tellingly, when you read Stroud’s character’s internal monologue, it really does sound like he’s reflecting on Neel’s status in the 1940s:

It was the literal truth that I myself had no idea what a Patterson would be worth, today, in the regular market. Nothing fabulous, I knew; but on the other hand, although Patterson had not exhibited for years, and as far as I knew she was dead, it did not seem possible that her work had gone into complete eclipse. The things I had picked up for a few hundred had been bargains when I had bought them, and later still the artist’s canvases had brought me much more, though only for a time.

Based on the biography of Phoebe Hoban Alice Neel: The Art of Not Being Pretty, the flea market scene was inspired by a real-life incident where Neel had to buy back his own WPA paints after they were sold off by the government and ended up in a Greenwich Village thrift store. (An article about the government’s sale of art appeared when Fearing was beginning his novel in an April 1944 issue of Life magazine, another Luce publication. It was illustrated with a painting by Neel.)

As portrayed in Fearing’s novel, Patterson is proudly unconventional, alcoholic, sarcastic, and hides her vulnerabilities by deliberately provoking the squares around her. “I’ve never been married,” she tells an investigator who asks where the father of her four children is, shocking him. “They are all LOVED children, Mr. Klausmeyer.” She presents herself, in other words, as a real character.

![Elsa Lanchester [left] plays Louise Patterson, a painter based on Alice Neel in The Big Clock](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2023/05/the-big-clock-1024x733.jpg)

Elsa Lanchester [left] plays Louise Patterson, a painter inspired by Alice Neel in The big clock (1948) (Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images)

In the 1948 film, Patterson is portrayed by Elsa Lanchester (the “bride” of Bride of Frankenstein) as dotted comic relief. Her big moment comes when she is tasked with painting the face of the man who bought her painting, thus threatening to find out Stroud’s identity. When she reveals the image, however, it is blobby abstraction – a joke at the expense of the then-rising vogue for abstract art which is very not about Alice Neel, who saw abstraction as anti-human and a form of bourgeois decadence. (You could, however, imagine that Neel is sabotaging the authorities: Oncewhen two FBI agents came calling to inquire about her communist ties, she refused to cooperate, offering to paint their portraits instead.)

Between the publication of Fearing’s novel in 1946 and the release of Farrow’s film in 1948, President Truman signed Executive Order 9835, designed to root Communists out of government, and the House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC) came into high season. The kind of leftist politics that had been prevalent among artists of all kinds during the New Deal era, which provided the first audience for both Neel and Fearing, could get you fired or ostracized.

Knowing this history and their biographies, the status of Patterson’s character in the Fearing story is actually poignant.

The big clock is about a man whose normal middle-class life is shattered by a false accusation. The character of the painter – free-spirited, impoverished and defiantly living outside the conventions of respectability – represents a cultural world that could incriminate you if you end up being associated with it, even without knowing it. The fact that Patterson potentially threatens to reveal George Stroud’s face in his art expresses anxiety about former comrades “naming names”. (When Fearing himself was called before the HUAC in 1950 to answer the question of whether he had been a member of the Communist Party, he replied with calculated irony: “Not yet.”)

Alice Neel around 1980 in New York. Photo by Sonia Moskowitz/Images/Getty Images.

I haven’t been able to find what Alice Neel’s thoughts were on the book or the movie. I see that in his official biography, Fearing, an alcoholic, would have told Neel that the financial success of The big clock had made the job more difficult, as he could afford to start drinking in the morning.

Farrow’s thriller isn’t actually the only time Alice Neel appears in fiction. There is also that moment when Susan Sarandon played her in independent film Joe Gould’s Secretdirector’s forgotten sequel to Stanley Tucci big night. A more flattering portrait, but less extraordinary in that it comes after Neel’s return to fame. And a story for another time….

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.