When tourist Fiona Foskett saw what looked like modern shoes in a centuries-old painting during a recent visit to London’s National Gallery, she laughed it off.

Portrait of Frederick Sluyskenby the 17th century Dutch master Ferdinand Bol, depicts the son of a wine merchant holding a goblet.

“I said to my daughter, ‘Wait, is he wearing a pair of Nike sneakers?'” she told the Sun. “Or,” she joked, “is he really a time traveler?”

It’s not hard to see why she might think so. His black shoes are adorned, in white, with what looks like very as does the brand’s iconic “swoosh” design.

The museum said it was delighted as the story was picked up by media from Shoe News At Daily mail. In fact, they were way ahead of Ms Foskett, tweeting an image of the painting as early as August, asking if anyone could see a ‘modern’ detail. (Some skeptics replied that it was just a piece of sock visible under a bow. One even asked the museum to stop taking drugs.)

It wasn’t the first time observers have spotted seemingly modern objects or people, in artwork dating as far back as before the birth of Christ. Maybe Foskett was onto something.

Every time someone spots one of these, the internet goes crazy and everyone laughs. But perhaps the proof that time travel really exists is hiding in plain sight, in museum collections around the world..

In addition to 17th century Nikes, here are six other examples of chronologically displaced, in works from ancient to disturbingly modern, which may have been accidentally saved for prosperity – at least until the time police arrive.

Grave Naiskos of a woman enthroned with an attendant (100 BC)

Grave Naiskos of a woman inducted with an attendant, on display in the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, which even appears to show USB ports on the side of a laptop computer. Courtesy of the Getty Foundation.

In this funerary relief, a little girl searches all over the world to hold a laptop in front of the deceased, represented on a throne to signal his status.

Even the artwork’s owner, the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, calls the object a container, but tellingly points out on its website that it “seems too shallow to hold anything substantial. “. In an explanation that would absolutely convince no one outside of an art history class, the museum compares it to similar objects in other works of art from which women pull ribbons or jewelry, concluding that is a jewelry box.

But maybe the truth is that Iktinos and Kallikrates designed the Parthenon using software like AutoCAD on their MacBooks.

Turkish seamstress mummy (c. 900 AD)

This Turkish seamstress, who died around 900 CE, wears what appears to be the first pair of Adidas sneakers. Courtesy of Mongolia Cultural Heritage Center.

This Turkish seamstress, whose remains were discovered by shepherds in Mongolia in 2017 and restored by the Mongolian Cultural Heritage Center, wore fashionable clothes.

The stripes are surprisingly similar to Adidas shoes, even though the German company wasn’t founded by Adi Dassler until centuries later, in 1949 – according to the official account, anyway.

But seeing as Adidas put a computer in a shoe as far back as 1984, the company was definitely ahead of its time. Could it have been… hundreds of years Ahead of its time?

First Nike, and now Adidas too? The clues keep piling up.

Ventura Salimbeni, Glorification of the Eucharist (late 16th century)

Ventura Salimbeni, Glorification of the Eucharist (late 16th century), via Wikimedia Commons.

Ventura Salimbeni’s painting in St. Peter’s Church in Montalcino, Siena, Italy isn’t even subtle about its anachronistic technology. Those with a fantasy art history degree from Vassar or Williams might be convinced that the large spherical object is “the globe of creation”, and the protrusions held by Jesus and the Heavenly Father are wands symbolizing their power.

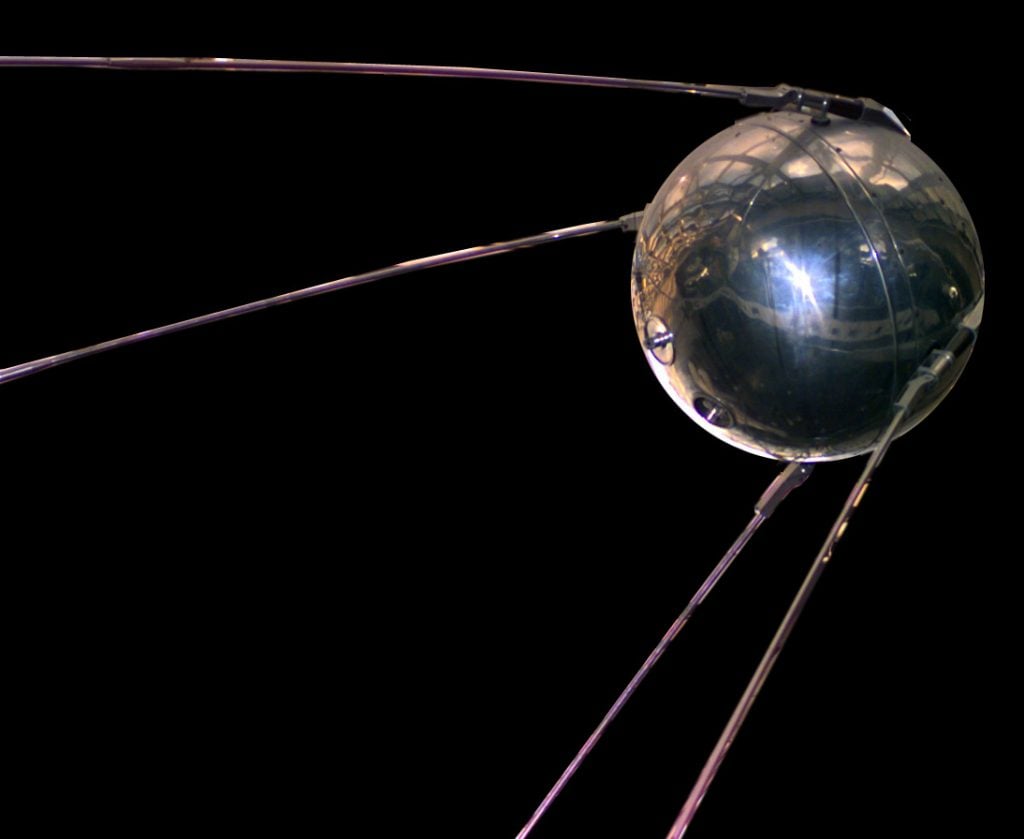

But the device bears an uncanny similarity to another celestial instrument.

A replica of Sputnik at the National Air and Space Museum. Courtesy of NASA.

A look at this replica of the first artificial satellite placed in outer space, launched by the Soviets in 1957, clearly shows why this work is commonly referred to as “Montalcino’s Sputnik”. It’s even the right size, nearly two feet in diameter, and pretty and shiny. Perhaps the Soviet satellite took an unplanned detour during its 98-minute circuit around the Earth, stopping at the end of the 16th century. Or maybe, as some say, the object held by God and His Son is just a UFO we want to believe.

Pieter de Hooch, Man handing a letter to a woman in the entrance hall of a house (1670)

Pieter de Hooch, Man handing a letter to a woman in the entrance hall of a house (1670). Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.

by Pieter de Hooch Man handing a letter to a woman in the entrance hall of a house held at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has such an innocuous, everyday title that it would be easily accessible to any casual observer off the beaten path to discover evidence of time travel.

But take a closer look at the letter in the man’s hand and try to figure out how this 17th century courier had an iPhone hundreds of years before anyone else. Even Apple CEO Tim Cook, who you might think would be happy to spread the news about technological advancements, joked about it, said at a press conference“I always thought I knew when the iPhone was invented, but now I’m not so sure.”

Maybe the courier was using Waze to find the fastest route for his delivery. And he’s not the only one staring at the screen…

Ferdinand George Waldmüller, The expected (1850 or 1860)

Ferdinand George Waldmüller, The expected (1850 or 1860). Courtesy of the Bavarian State Painting Collections.

Ferdinand George Waldmuller The expected is a classic genre painting from the end of the Austrian painter’s career, showing a young man in love in his Sunday clothes, waiting with a flower for the object of his affections, who has not yet seen him. According to experts at the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, where the painting hangs, it is because she is absorbed in a hymn. Or is it really because his attention is fixed on an object in his hands that looks suspiciously like a cell phone.

What other are these museums hiding in their vaults?

Umberto Romano, Mr. Pynchon and the Springfield facility (1937)

Our final example is perhaps the most complicated and sinister.

Painting by Italian artist Umberto Romano Mr. Pynchon and the Springfield Institution shows a pre-revolutionary encounter in the 1630s between English settlers and two New England tribes, the Pocumtuc and the Nipmuc.

But what is the Native American figure in the scene holding in his hand if not an iPhone, a technology apparently only introduced in 2007? (He might even read a text from the young woman in Waldmüller’s painting above, suggesting that the young man with the flower is destined to be disappointed.)

write for ViceBrian Anderson went to great lengths on this one, pointing out that the titular William Pynchon depicted in this painting is the ancestor of conspiracy novelist Thomas Pynchon, who was born in – brace yourself – the same year the painting was completed. A historian told Anderson that the object in question is likely a mirror, which was a symbol of wealth and prestige for Native Americans, and which William Pynchon may have brought to charm Native people.

Do you know what else has a mirror screen? That’s right. An iPhone, brought by a time traveler.

The facts are all there, if you are brave enough to see them.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.