Starting a career as an artist can be difficult, especially in New York City where the cost of living and competition have historically been and continue to be incredibly high. Enter the day job. For decades, if not centuries, artists have sought stable employment – and steady pay – to support their artistic practices. However, many have been fortunate enough to stay within reach of the art world, working at world-renowned institutions by day while honing their practices by night.

New York City is home to more than 80 museums, many of which are dedicated to the visual arts. These multi-faceted institutions require a range of specialist personnel, from pickers and carpenters to administrators and security guards. It’s perhaps no surprise that some of the most famous artists of the last century have found employment within their legendary walls, ranging from book counter to museum custodian.

Below, we’ve rounded up five famous artists of the 20th century who spent time early in their careers working behind the scenes in museums before making it big.

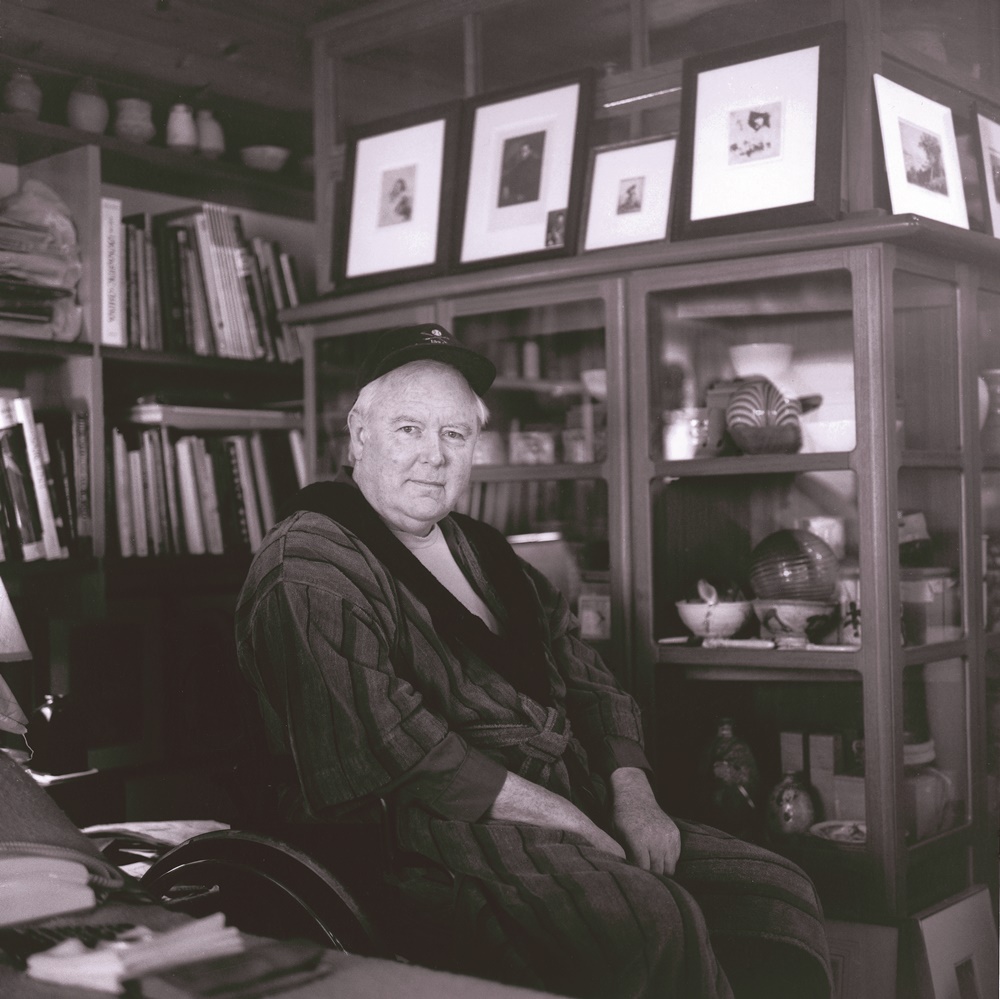

Robert DeNiro, Sr.

Robert De Niro, Sr. (c. 1980) in New York. Photo: Sonia Moskowitz/IMAGES/Getty Images.

Robert De Niro, Sr. (1922–1993) – father of Academy Award-winning actor Robert De Niro, Jr., of angry bull And The Godfather Part II fame – was an accomplished artist noted for his impressionistic abstractions. He studied at the famous Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where Professor Joseph Albers noted him as one of his best students before De Niro enrolled at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts. In 1940 De Niro wrote to Baroness Hilla von Rebay, who had established the Museum of Non-Objective Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation a few years earlier, telling her of his financial difficulties as well as his hope that she could see some of His paintings. Rebay’s secretary provided De Niro, Sr. with a check for $15 to cover art supplies, a small act of support that would be repeated in subsequent years. In 1943, the artist took on the role of security guard and night watchman at the Museum of Non-Objective Art. He worked there until the late 1940s, although sadly most of his work from that time was lost due to an attic fire in 1948.

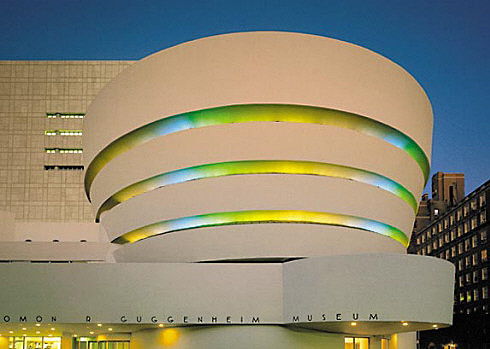

Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock (1953) in East Hampton, New York. Photo: Tony Vaccaro/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Another New York-based artist joined the staff of Rebay’s Museum of Nonobjective Art in early 1943: Jackson Pollock (1912–1956). Employed as a caretaker and maintenance man, he still managed to spend much of his time working on his art, and ultimately his tenure at the museum proved brief. Shortly after taking the job at the museum, he submitted one of his works for consideration at the Spring Salon for Young Artists at Peggy Guggenheim’s influential Art of This Century gallery, which was located nearby. At the request of the salon’s jurors – Piet Mondrian and Marcel Duchamp – Guggenheim offered Pollock a multi-year gallery contract and a monthly stipend that allowed him to quit his job at the museum and devote his time exclusively to his painting. The deal also included the promise of a solo exhibition at the gallery in the fall of that year, and a commission for a site-specific painting for the Guggenheim townhouse on West 57th, which resulted in the monumental work Wall (1943), ultimately the greatest work of Pollock’s oeuvre.

Dan Flavin

Dan Flavin at his home in Wainscott, New York, 1995. Courtesy of Stephen Flavin.

More than any other artist on this list, Dan Flavin (1933-1996) had the most varied careers of museum support staff. He worked in the mail room of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; as custodian at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) between 1959 and 1960; and as a caretaker at the American Museum of Natural History in the summer of 1961, the latter of which coincided with his early experiments incorporating electric lights into his work. The influence of Flavin’s various odd jobs at different institutions—and the people he met at each position—is evident in many of his works.

Dan Flavin, untitled (to Ward Jackson, an old friend and colleague who, in the fall of 1957, when I finally returned from Washington to New York and joined him to work together in this museum, kindly communicated) (1971).

Pieces from one of Flavin’s most significant series, the “Icons”, inspired both by Christian iconographic painting and the aesthetic values of Suprematism, frequently featured dedications. For example, icon I (the heart) (in light of Sean McGovern who blesses everyone (1961-1962), the so-called McGovern was a caretaker and elevator operator alongside Flavin at the American Museum of Natural History. Gus Schultze’s screwdriver (to Dick Bellamy) (1960) refers to an art preparator named Schultze who worked concurrently with Flavin at MoMA. And, perhaps the most descriptive, the 1971 piece untitled (to Ward Jackson, an old friend and colleague who, in the fall of 1957, when I finally returned from Washington to New York and joined him to work together in this museum, kindly communicated)– with Ward being one of Flavin’s co-workers in the Guggenheim mailroom.

Sol LeWitt

Solomon “Sol” LeWitt (1978). Photo: Jack Mitchell/Getty Images.

Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) joined the MoMA staff in 1960, getting a job through his cousin – who was already working at the museum – at the book counter. About a year later, his role changed and he took over the cover of the evening front desk at the 53rd Street entrance. During his tenure, he met many other artists who also held positions at the museum, including Flavin, Bob Ryman, Lucy Lippard, Scott Burton, and even Jeff Koons, among others. From his experience working at MoMA, Lewitt thinks later, “If I hadn’t worked here and known Flavin and Ryman and Lippard and a few other people, maybe it wouldn’t have clicked. We never know; he may or may not have. But he did. So it was crucial. The policy they had of employing artists as guards and people doing odd jobs was, I think, a very good policy. In LeWitt’s oral history later picked up by the museum, the artist describes several playful interactions with then-museum director Alfred Barr, including expressing his displeasure with certain sculpture installations visible from his office.

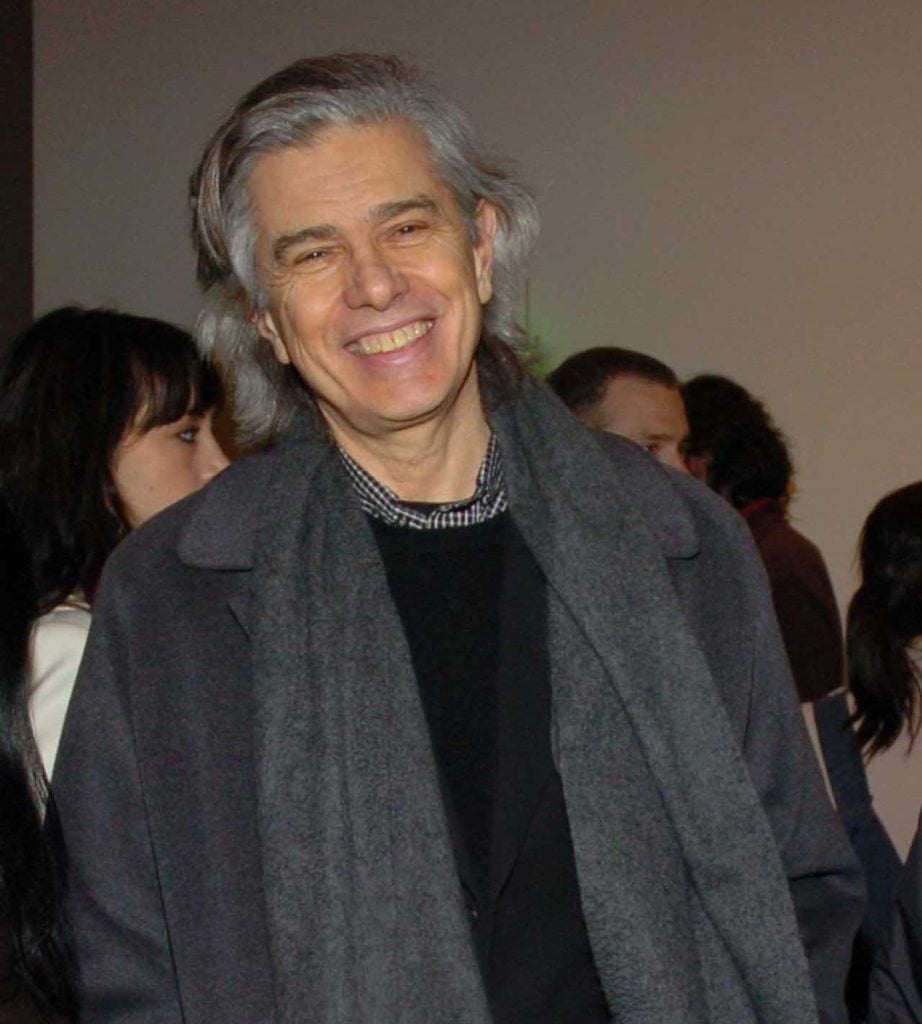

Mel Bochner

Mel Bochner (2005). Photo: Joe Schildhorn/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

In the mid-1960s, conceptual artist Mel Bochner (b. 1940) accepted a job as a security guard at the Jewish Museum to support his art practice. Spending his days working at the museum and his nights painting, the lack of rest eventually caught up with him. Bochner later recounted, “I would come to work tired. One day I got caught taking a nap behind a Louise Nevelson sculpture and got fired. Although the untimely siesta ended his career as a museum custodian, it was not the end of his association with the Jewish Museum: in 1970 his work was included in the group exhibition “Using Walls” and in 2014, the museum mounted the major solo exhibition ‘Mel Bochner: Strong Language’, which the museum advertised as a ‘sort of homecoming for the artist’, replete with a photo op with the current team of guards .

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.