King Charles, as the new custodian of the royal collection, will now face ethical questions about items seized during British military operations in Africa, when his great-great-great-grandmother Queen Victoria was on the throne. These looted objects came mainly from countries that are today Nigeria, Ghana and Ethiopia.

Unlike most UK national museums, the Royal Collection can be alienated, provided this is advised by its trustees and authorized by the monarch. The collection does not belong to Charles personally, but he holds it in trust as sovereign to pass on to his successor. Although this may seem to prohibit alienation, in the past it has sometimes been done when deemed appropriate, so it can be assumed that the tradition of the monarch

the obligation is to hand over the essentials of the collection.

There have been at least two occasions when Queen Elizabeth II has returned looted material. During a state visit to Ghana in 1961, she presented five Asante objects to the National Museum in Accra: two royal chairs, two stools and a state umbrella. Four years later, the Queen returned a crown and a Great Seal during a visit to Ethiopia.

A spokesperson for the Royal Collection tells The arts journal“Questions regarding the return of the objects are the responsibility of the trustees of the Royal Collection Trust, who take advice from a range of external bodies, including the government.”

The current chairman of the trust, a charity which administers the collection, is banker James Leigh-Pemberton, with Charles as patron. Two new curators, appointed in April 2022, will take a fresh look at the objects seized during the colonial period.

Tonya Nelson, who grew up in the United States, has a legal background. Before her appointment, she organized a meeting of the International Council of Museums (Icom) to discuss “restitution and decolonization”. Report on this for The arts journal in September 2019, she wrote that the meeting discussed dismantling “hierarchies and structures that exclude certain voices and perspectives from museum work.”

Monisha Shah, the other new director, is an Indian-born media professional who focuses on the creative industries. She previously served as a trustee of the Tate and the National Gallery.

Massacres, battles and wars

So how did the disputed material enter the royal collection? The Nigerian artifacts were seized during the punitive expedition against the Oba (King) of Benin in 1897, following a massacre of officials of the Compagnie Royale du Niger and their armed African porters. The Oba was overthrown and his Benin kingdom came to an end. Thousands of royal objects, including the famous Benin Bronzes, were looted from its capital, Edo (now Benin City).

The Ghanaian material came from the Asante (Ashanti) kingdom. During the Third Anglo-Ashanti War of 1873-1874, British forces occupied the capital Kumasi, destroying the royal palace and looting the regalia of Asantehene (King) Kofi Karikari. He was forced to abdicate. The royal treasures, many of which were gold, were taken to Britain.

Ethiopian artefacts from the royal collection were looted after the Battle of Maqdala (Magdala) in 1868. Rather than surrender, Emperor Tewodros II committed suicide, apparently with a weapon given to him by Queen Victoria . British troops looted royal possessions and churches.

Restitution will hardly be at the top of the royal agenda, and when it is considered, Charles will seek advice from the Director of the Royal Collection. But wishing to strengthen relations with the Commonwealth, the new monarch will probably see the importance of taking positive steps. Barely crowned, he will also be extremely sensitive to the meaning of traditional royal regalia.

The current Asantehene, Otumfuo Osei Tutu II, came to London for the coronation and visited Charles on 4 May. No doubt the ruler of Asante felt this would be an inappropriate occasion to raise the matter, but he must have been all too aware that some of his ancestor’s regalia were on display in the grand vestibule of Windsor Castle.

The Asantehene also met with the director of the British Museum, Hartwig Fischer, calling for the return of Asante objects seized in the 19th century. A museum spokesperson confirmed that the possible loan of objects to Ghana had been discussed.

Key pieces from the royal collection

Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III

Benin ivory leopards (19th century), on long-term loan to the British Museum

A pair of carved ivory leopards, made from ten tusks, with inlaid copper spots (probably reused from rifle percussion caps). Leopards are considered the “kings of the forest”, representing a symbol of royal authority in Benin. After the capture of Benin by British troops in 1897, this pair was acquired by Admiral Harry Rawson, who presented them to Queen Victoria. In 1924 George V sent them on long-term loan to the British Museum, where they remain and are on display in the Sainsbury’s Africa Galleries.

Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III

Beninese head of an Oba (circa 1650), on display at Windsor Castle

The bronze head of an Oba originally stood on a shrine in the royal palace until the sculpture was seized during the 1897 expedition. It was brought to the UK by an officer and sold later. The sculpture was purchased in the late 1940s or early 1950s for the National Museum of Nigeria. As The arts journal revealed, in 1973 it was seized from the Lagos Museum by General Yakubu Gowan, the Nigerian President, who presented it to Queen Elizabeth during her state visit. It was therefore looted twice.

Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III

Asante gold trophy head (19th century), on display at Windsor Castle

These golden hollow masks with human features were made using a sophisticated lost-wax technique. They represented defeated enemies of the Asante and were attached to ceremonial swords. This example was part of the regalia of Asantehene Kofi Karikari and was seized by British troops at Kumasi in February 1874. Three months later it was purchased by Queen Victoria.

Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III

Asante State Sword (19th century), on display at Windsor Castle

These state swords were carried by high-ranking members of the Asante court. The wooden handle is covered with gold leaf. It would also have belonged to Asantehene Karikari. After its seizure in 1874, General Ponsonby wrote to Queen Victoria, saying that British officers “consider it their duty as well as an honor to submit these articles – or the best of them – to Your Majesty before selling them publicly”.

Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III

Slippers of Emperor Maqdala (mid-19th century), not visible

This pair of slippers, decorated with gold filigree and set with amethysts, belonged to Emperor Tewodros. They were seized by General Robert Napier at Maqdala in 1868, after the Emperor committed suicide, and then presented to Queen Victoria. For conservation reasons, the slippers are not on display.

Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III

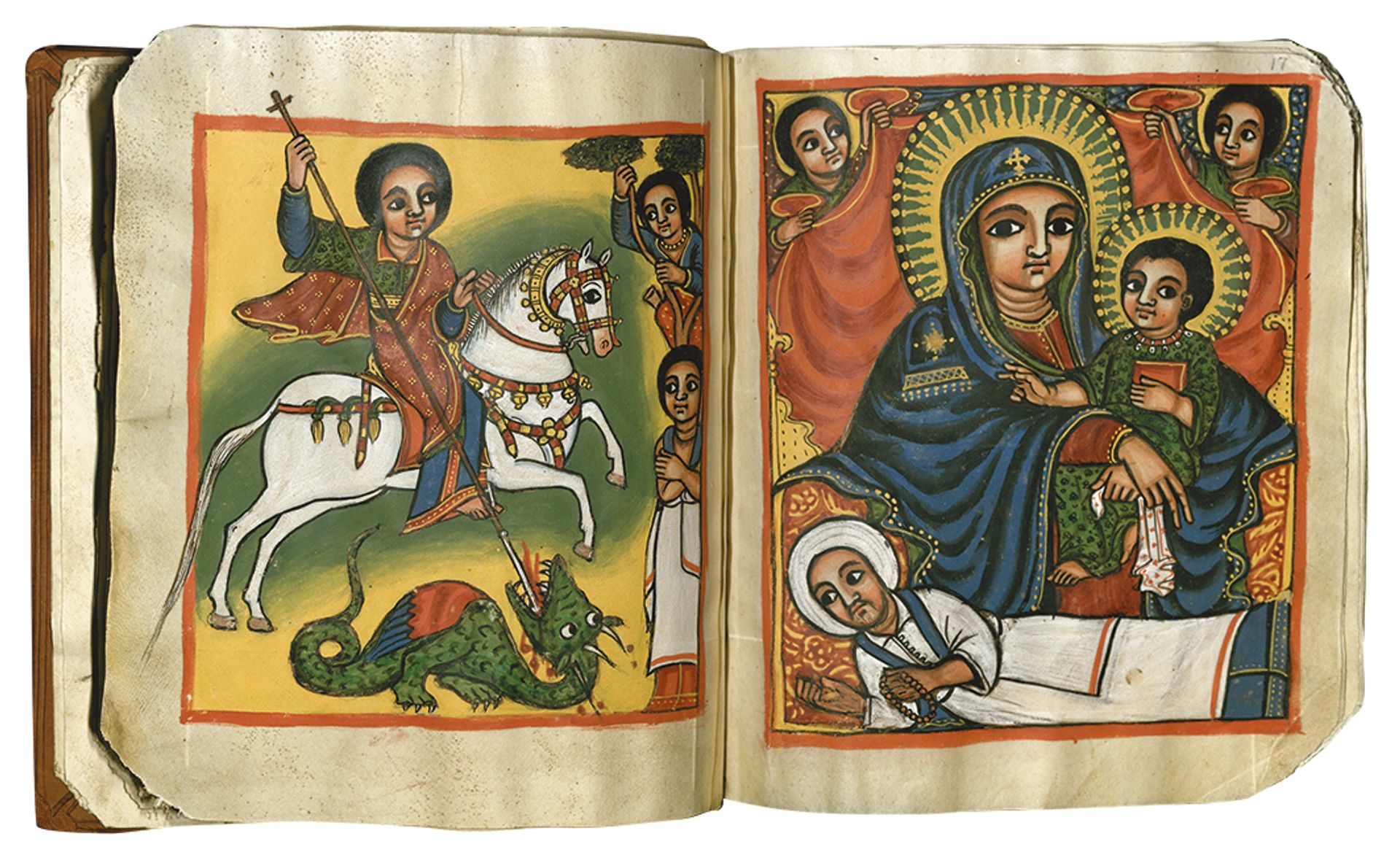

Maqdala Miracles Manuscript (1766), not visible

An illuminated manuscript on vellum from the Miracles of the Virgin Mary in Ge’ez, the Ethiopian liturgical language. The book has 13 painted pages, including a Madonna and Child, inspired by the Byzantine icon (perhaps 6th century) currently in Rome at Santa Maria Maggiore. THE miracles was seized from Madhane Alam Church in Maqdala and quickly acquired by British Museum agent Richard Holmes. He presented it to Queen Victoria. The manuscript was bound in London by the India Office in the late 19th century. It is also not visible for conservation reasons.