They were known as the “three witches”.

In the feverish cultural milieu of Mexico City in the 1930s, artists Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna were closest friends and frequent artistic collaborators. Each European expatriate – Carrington from England, Varo from Spain and Horna from Hungary – these women came to Mexico to flee war and persecution and found kindred spirits with common interests in witchcraft, alchemy and the tarot, passions that have bled into their lives. strange works of art and collaborative visions.

Yet history has remembered their legacy unevenly. While in recent years Carrington and Varo have become household names amid reexaminations of the role of women in the development of Surrealism, Horna, however, has remained a surprisingly obscure figure.

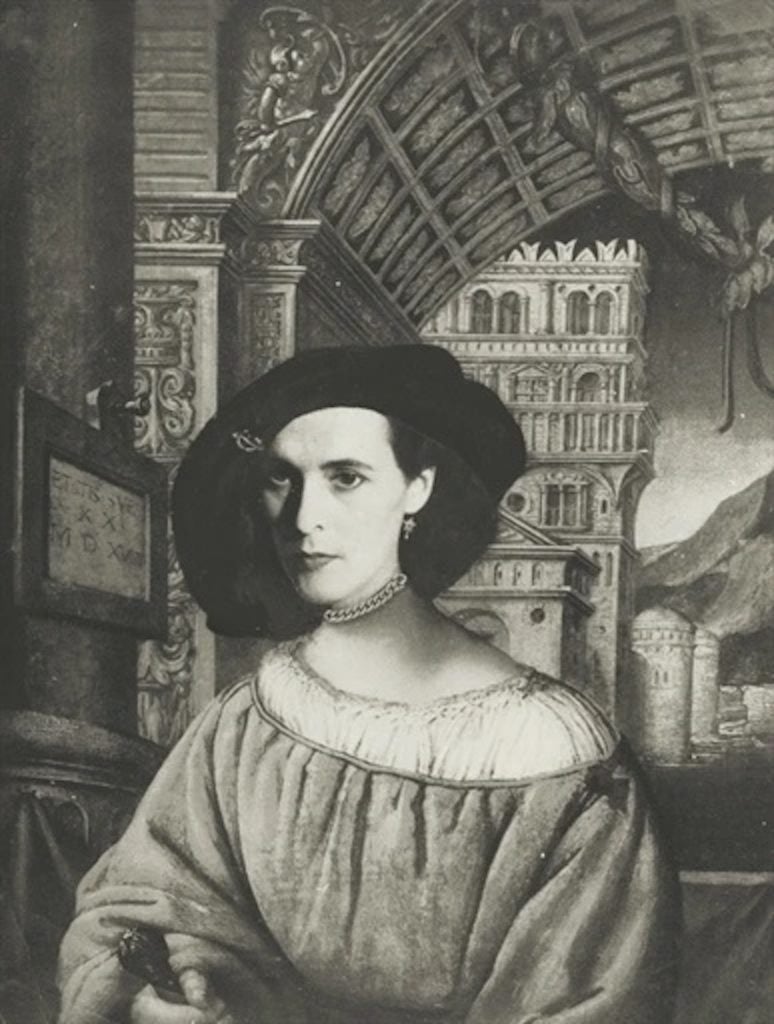

Kati Horna, Portrait of Leonora Carrington (1960/1987). Courtesy of Ruiz-Healy Art.

But her weird and beautiful photography can now catch a new light. New York’s Ruiz-Healy Art currently presents “Kati Horna: On the Move“-THE first exhibition dedicated to Horna’s work in the city. This haunting exhibition brings together photographs taken from the 1930s to the 1960s and offers a window into Horna’s inner world, a world filled with mysticism and loss shaped by a war-torn life.

Horna was born Katalin Deutsch in Budapest in 1919 to an upper-class Jewish family (Horna would marry artist Jose Horna in Paris in the late 1930s). She lived among the city’s intelligentsia and was a childhood friend of Robert Capa, studying photography alongside him. As a teenager, she apprenticed with the famous photographer József Pesci, whose avant-garde imagery bridged the gap between advertising and constructivist aesthetics.

By his twenties, Horna had moved to Berlin, befriending Bertolt Brecht, Walter Benjamin, and fellow countryman László Moholy-Nagy. The turbulence of the time dragged him all over the continent. In 1933, she traveled to Paris, becoming entangled in the surrealist movement. A leftist driven by her politics and a supporter of the Spanish Republican cause, she quickly settled in Spain, working as a war photographer during the Spanish Civil War, for a time bonding with Capa. These photojournalistic images have been widely distributed, particularly in the Illustrated press (The Society of the Americas of New York presented a selection of these works in 2016), and while the exhibition at Ruiz-Healy focuses primarily on Horna’s artistic activities carried out in Mexico, dealer Patricia Ruiz-Healy says that his photojournalism – and his wartime experiences – are key to understanding his work.

“Kati’s photojournalism has given her economic independence and the ability to pursue her political beliefs. Her father died when she was 18 or 19 and she invested an inheritance from her father in buying a camera and for photography lessons,” said Patricia Ruiz-Healy, in a conversation, “It gave him creative freedom.

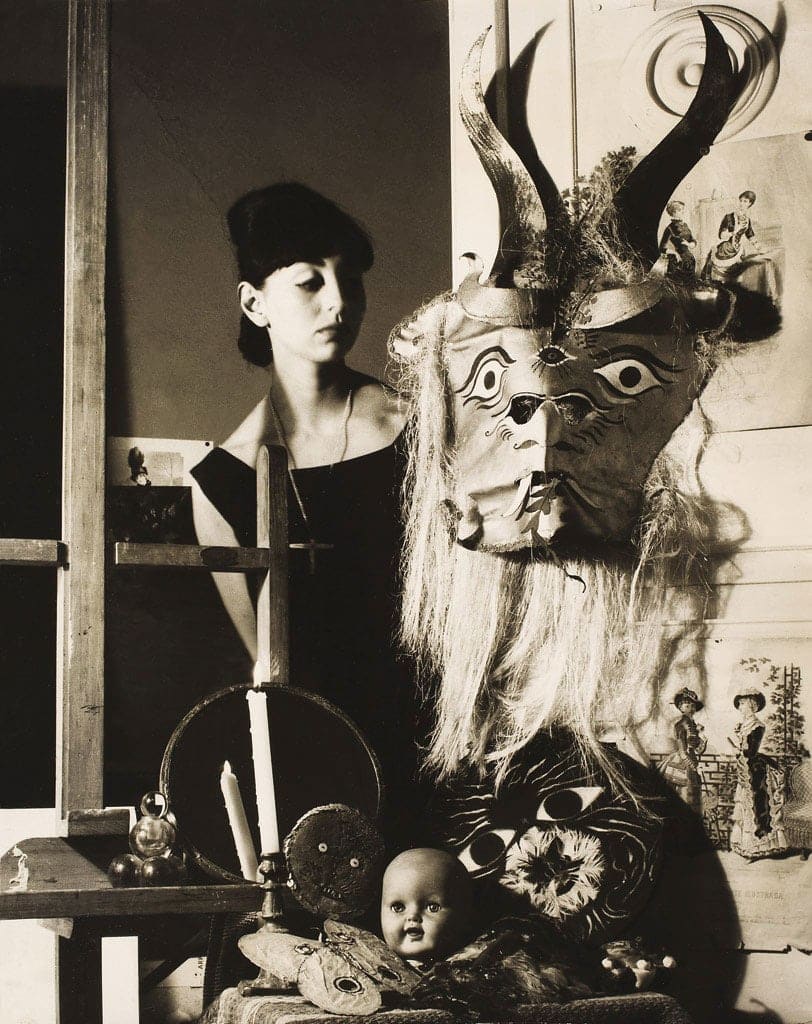

Kati Horna, Mujer Con Mascara (1961) from the series “Mujer Y Máscara”. Courtesy of Ruiz-Healy Art.

Returning to Paris in 1938, Horna and her husband would again be driven to flee the following year as France fell under Nazi occupation. This final exodus will lead the artist to Mexico, a country she will love deeply and which will allow her to take refuge in artistic experimentation. “I’m allergic to the question of where I come from,” Horna wrote. “I fled Hungary, I fled Berlin, I fled Paris and I left everything behind in Barcelona… When Barcelona fell, I couldn’t go back to get my things, I still lost everything. I arrived in a fifth country, Mexico, with my Rolleiflex around my neck, and nothing else.

In these photographs from the Mexican era, we notice certain recurring fascinations: dolls and masks, surreal and occult imagery, the life of his friends. Again and again, Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo appear captured in time, like other artists and actors of the era, in images that are both staged and candid. Varo leans against a windowsill, smoking a cigarette, in a photograph, captured as if in the middle of a conversation. In another, Carrington paints at his easel, with relaxed familiarity.

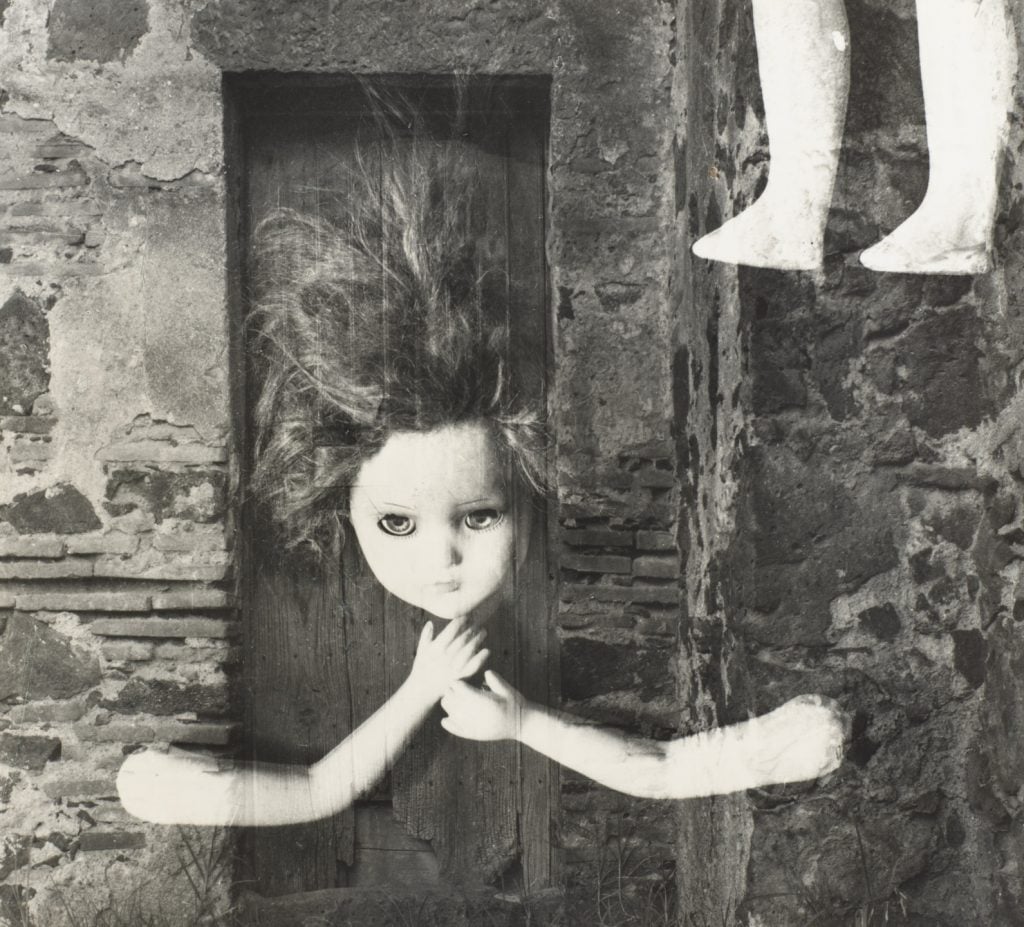

Kati Horna, Leonora from the series “Oda A La Necrofilia” (Ode to Necrophilia) (1962). Courtesy of Ruiz-Healy Art.

“Kati captures Carrington and Varo in their most intimate settings. They seem so relaxed – painting, working, socializing. These are often images of good times, fun times, which are all the more striking when you consider how much these people have all suffered in their lifetime,” Ruiz-Healy said. “Such.” Other photographs are materially and technically experimental, and the exhibition includes photomontages and photocollages. In keeping with Horna’s surrealist leanings. In one photograph, actress Beatriz Sheridan leans her face against a mirror, appearing as a decapitated saint or a jellyfish, seemingly offering her peculiar reflection. In another, an unidentified model is photographed through a glass jug, creating a ripple effect on the flat surface of the photograph. Carrington, in particular, often appears as Horna’s model and muse, her face photo-collated, in a single image, in an architectural space a la Di Chirico. Varo and Carrington also appear obliquely, in masks and other objects made by the artists (in one of Horna’s photographs, Carrington is depicted in a mask made by Varo, encapsulating their artistic trinity).

Masks are one of Horna’s most enduring symbols. In a wonderfully bizarre series, “Ode to Necrophilia” – which Horna directed for the avant-garde magazine SNOB in 1962 – Carrington appears naked, seated and crouching next to a crumpled bed. In what seems a twilight light, her face turns away from the viewer, on the pillow rests a haunting white mask.

Kati Horna, Untitled (1933/1960) from the series “Flea markets, Paris”. Courtesy of Ruiz-Healy Art.

“These are death masks,” explained Patti Ruiz-Healy, daughter of gallery founder Patricia and director of the New York space. “Often a cast was made from the face of a loved one when they died.”

The images are surprisingly serene. “These photographs were taken in the early 1960s, at a time when Kati’s husband, Jose, was very ill and soon died. Remedios, who was like a sister to her, was also very ill and died in 1963. It was a way for Kati and Leonora to mourn those people in their lives,” said Patricia Ruiz-Healy. The title “necrophilia” here alludes to the physical love, longing, and embodied mourning for loved ones who are dying or have passed away.

Death pervades every hidden corner of his oeuvre, it seems, and perhaps Horna’s most telling imagery is entirely absent from living figures, instead depicting jumbles of broken dolls in live images. black and white. The 1962 series “A Night at the Doll Hospital” focuses entirely on such images, and although superficially these images may recall the darkly surreal photographs of Hans Bellmer, upon closer examination Horna’s series is a deeper contemplation. tender of innocence and its loss.

Kati Horna, Untitled (1962) from the series “Una Noche en el Sanatorio De Muñecas” (A Night at the Doll Hospital). Courtesy of Ruiz-Healy Art.

“What she saw in Spain marked her forever. She would go to cities and see women and children lying dead in the streets with dolls and toys abandoned next to them,” said Patricia Ruiz-Healy, “The dolls are very symbolic for her. In the series ‘The Night at the Doll Hospital’, there is a hope to fix them.

Horna lived in Mexico until her death in 2000 and continued working late in life. Patricia and Patti Ruiz-Healy believe part of Horna’s obscurity is due to the scarcity of her work in the marketplace. The Merchants were introduced to Horna’s daughter, Leonora (named Carrington), who runs her mother’s estate with her children, but an exhibit took years to put together. “Horna only made a selective reprint of his vintage prints in the 1960s and donated much of his archive to the Spanish government and a research institute in Mexico City,” said Patti Ruiz -Healy. Nevertheless, his notoriety continues to grow in institutional circles. His works were included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Beyond Surrealism” exhibition in 2021. When asked what Horna would have thought of the prospect of artistic fame, dealers were wary, given Horna’s policy. “She considered herself an art worker, not an artist,” noted Patricia Ruiz-Healy.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.