On the improvised dance floor of the Chase Contemporary gallery, the 80s are in full swing. Gloria Gaynor steps out of the DJ booth, churning out hip moves reminiscent of a time when a Soho party meant something completely different. Someone is draped in a boa, how ironic it is hard to tell.

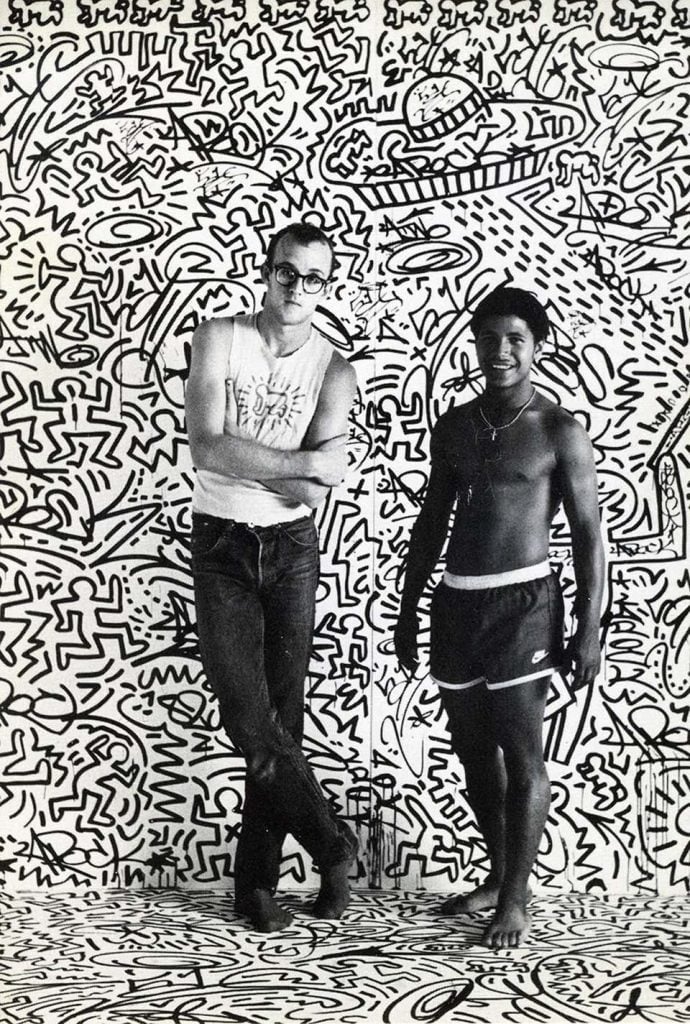

The gathering is here to celebrate the latest episode of Angel Ortiz’s comeback,”Ode 2 New York‘, a collection of new works on display until June 18. And in case young latecomers don’t know which party they’re crashing at, it’s proclaimed on a giant black-and-white photo hanging above the bar champagne: Ortiz (alias LA II) rubs shoulders with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Kenny Scharf. “You are in the presence of New York street art royalty,” the message read.

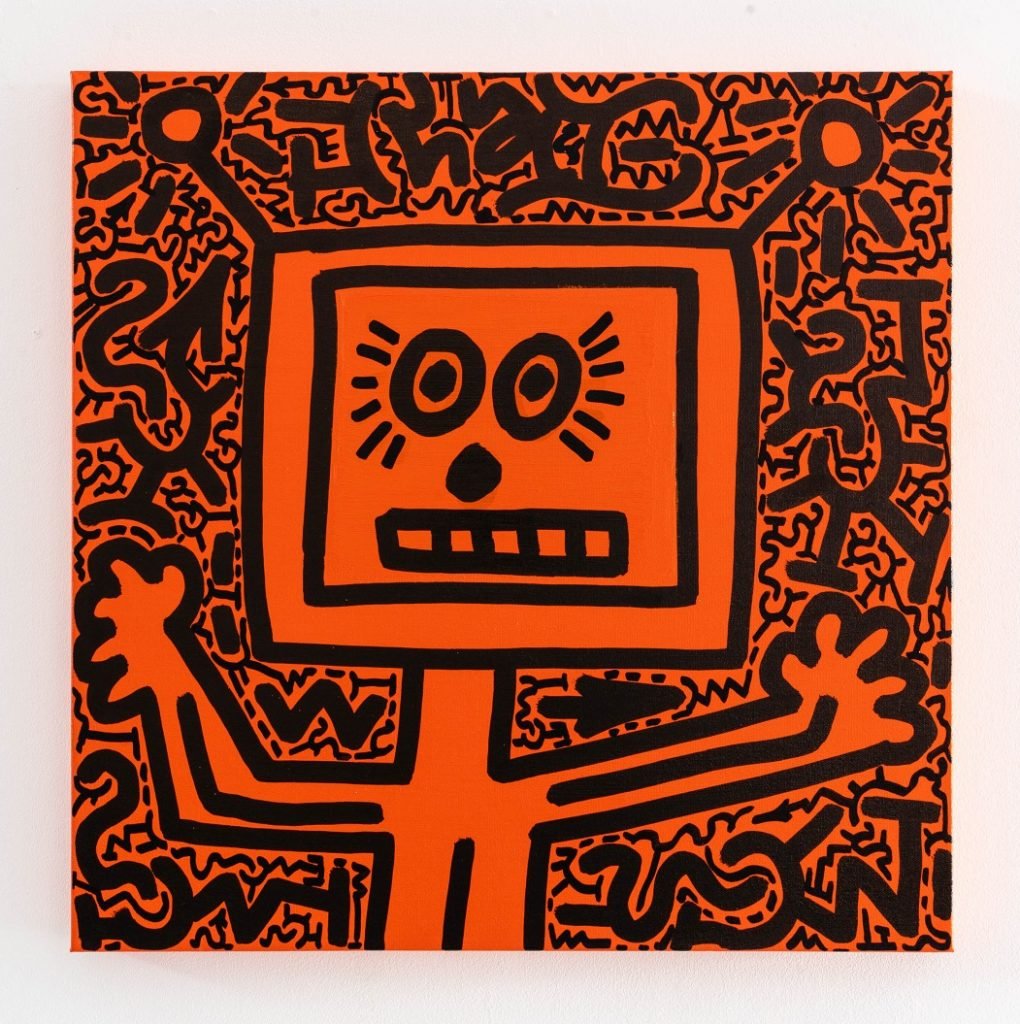

Angel Ortiz, Shazbot (2023). Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

Ortiz is bent over a folding table by the door, labeling posters, t-shirts, hats and, frankly, anything he can work on with a large marker. He wears a tattered backpack almost all the time, as if at any moment he could rush off and find something more interesting to do. It seems unlikely. He’s surrounded by friends and longtime fans, apparently enjoying his reappearance in the spotlight. But then again, that wouldn’t be entirely out of place given Ortiz’s line of work.

Ortiz was barely a teenager when he burst onto the city’s street art scene in a highly crafted caption that goes like this: The Lower East Side native and his graffiti crew, the Non Stoppers, had painted the area bomb for years. when Ortiz’s dense lines caught the eye of Keith Haring, then a student at the School of Visual Arts. Haring was relentless in his search for the creator of the LA II beacon, eventually finding “Little Angel” and beginning a long run collaborative partnership. It was mutually beneficial, with Haring gaining local street access and acceptability, and Ortiz tapping into an international art market that was developing a sudden taste for street art.

Keith Haring and Angel Ortiz in front of a work on which they collaborated. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ortiz’s success story is so tied to Haring that it would be understandable if, 40 years later, the Puerto Rican would feel frustrated with that tie, as if it diminished the merits of his own art. Not so. Ortiz remains enthusiastic about his relationship with Haring. He’s also clear-eyed that it was Haring who approached him and asked for help (and, it seems, was inspired by the bold work of LA II).

“My relationship with Keith has always been about friendship first and the artistry was and always will be secondary,” Ortiz told Artnet News. “Keith asked me for advice on how to accentuate his isolated characters and give them a more complex environment for them to visually come to life. The collaborations artistically were magical and will never be duplicated.

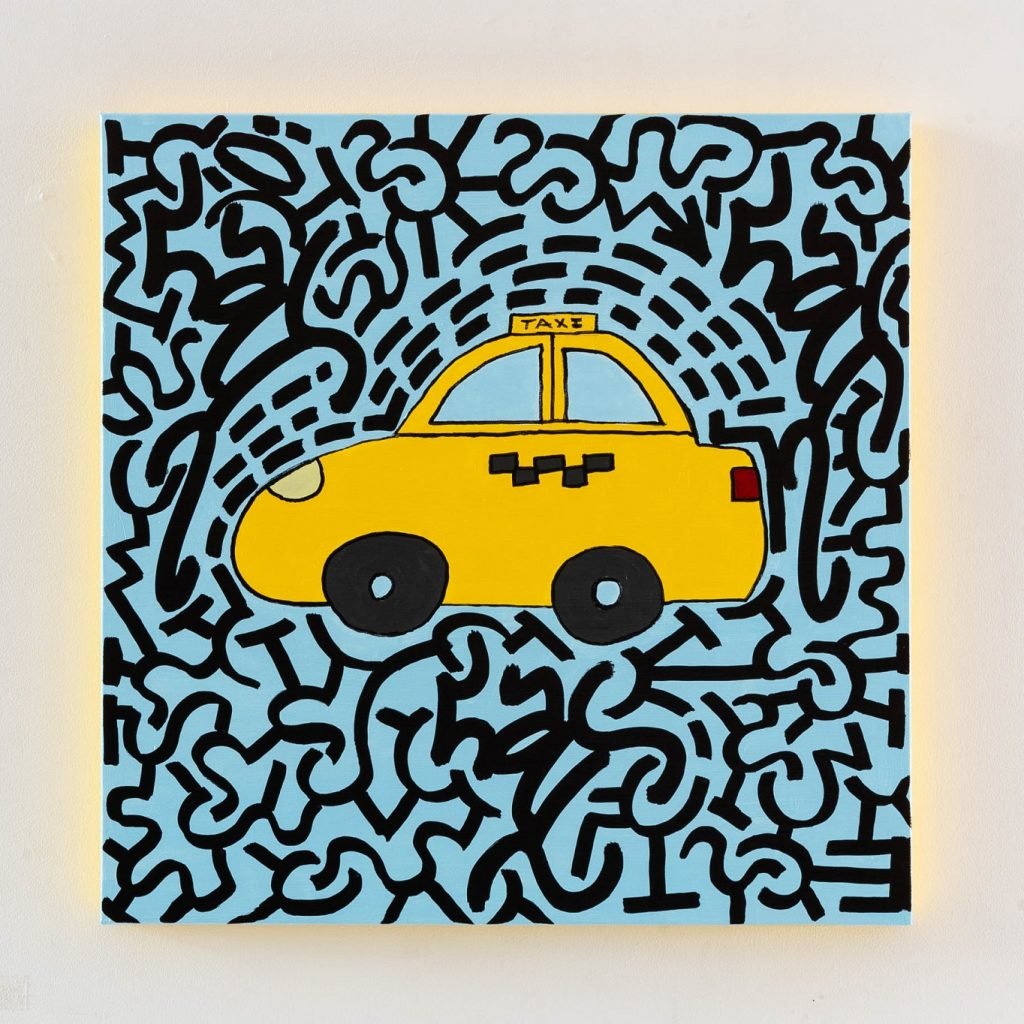

Angel Ortiz, Hudson (2023). Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

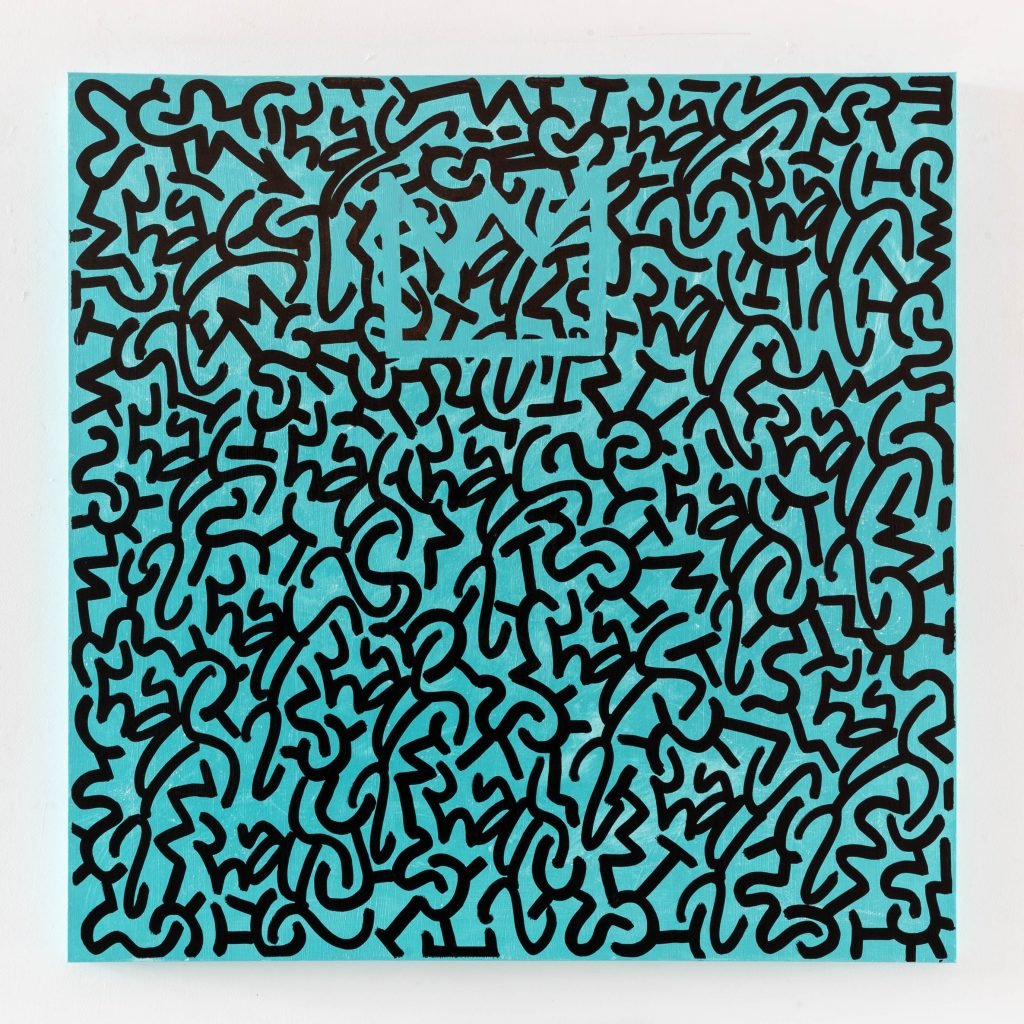

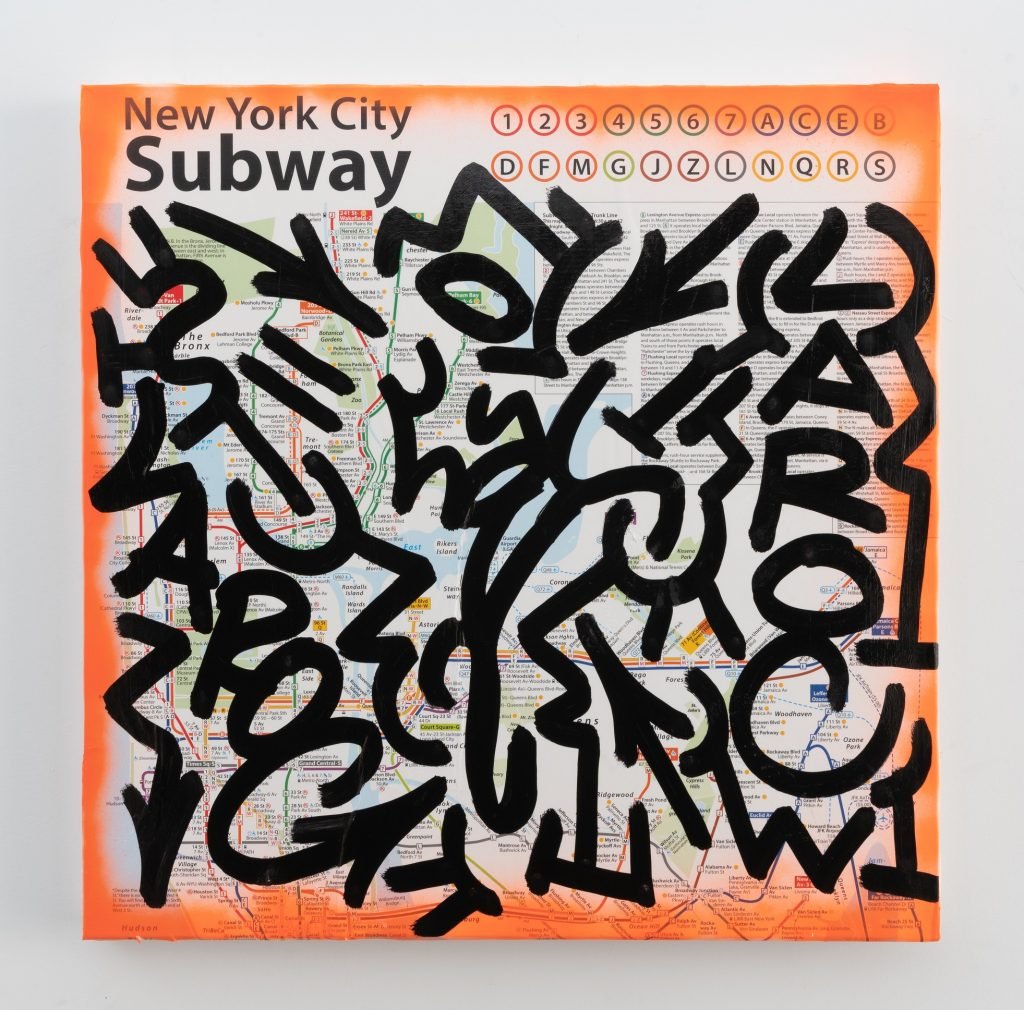

Ortiz’s latest collection follows a sold-out show at the The D’Stassi Gallery in London in 2022 and sees him continue to transfer his distinctive labels, symbols and icons from the city surface to the canvas. To see Ortiz’s current work is to step into a maze of arrows, lines to nowhere, half-formed letters, calligraphic flourishes, bold outlines, and negative spaces. Often, Ortiz orients his works around his formative motifs: the heart, the crown, the cat, the taxi (a nod, perhaps, to Ortiz’s first collaboration with Haring on a taxi hood), and the spray can, which, on location in Soho, sprouts arms and legs that stretch across the gallery wall.

In “Ode 2 NYC”, as in London, Ortiz also uses the paintbrush more often than the spray can. “I feel differently depending on the medium I’m using, and I feel most artistically free when I have a spray can in my hand,” Ortiz said. “When I use a brush on canvas, it is artistically the most ruthless of all my weapons of choice.”

Ortiz’s expertise with a marker compensates for any lingering uncertainty he may have with more traditional art tools. In works like Big Apple (2023) and Gotham (2023), the movement of thick and thin lines creates the context in which the painted symbols are located.

Angel Ortiz at the opening of “Ode 2 NYC”. Photo: courtesy Chase Contemporary.

But there is a contradiction at play here. Although Ortiz’s lines and patterns echo the era in which they were born, the complexity, polish and arrangement of his works which are conveniently presented on canvas lose their urgency, this connection to the surface of the city. And that’s good: artists are constantly evolving, retooling, reframing. It’s just more shocking in the context of graffiti.

It’s a shift that Ortiz himself acknowledges. “Graffiti in the 1980s was free from social media and the idea of branding,” he said. “Today’s graffiti isn’t bad; it’s just different. It’s like comparing professional sports from the 80s to today. Basically the same sport, just a completely different game.

See more images from the show below.

Angel Ortiz at the opening of “Ode 2 NYC”. Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

Installation view of “Ode 2 NYC”. Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

Angel Ortiz, Walter (2023). Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

Angel Ortiz, Untitled (2023). Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

Installation view of “Ode 2 NYC”. Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

Angel Ortiz, Metro (2023). Photo courtesy of Chase Contemporary.

“Ode 2 New Yorkis on view at the Chase Contemporary, 413-415 West Broadway, New York, through June 18.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.