As a child, artist Chris Oh (b. 1982) spent hours copying drawings from encyclopedias at his parents’ home in Portland, Oregon. “I had these World Book encyclopedias from the 1990s that I was really leaning on, copying anatomical maps and space,” he told me over the phone, “I would do it over and over again. I thought it was really fun.

Memory is revealing; the Queens, New York-based artist is known for his amazingly accurate replicas of historic – mostly Renaissance – artwork that he paints on unexpected objects.

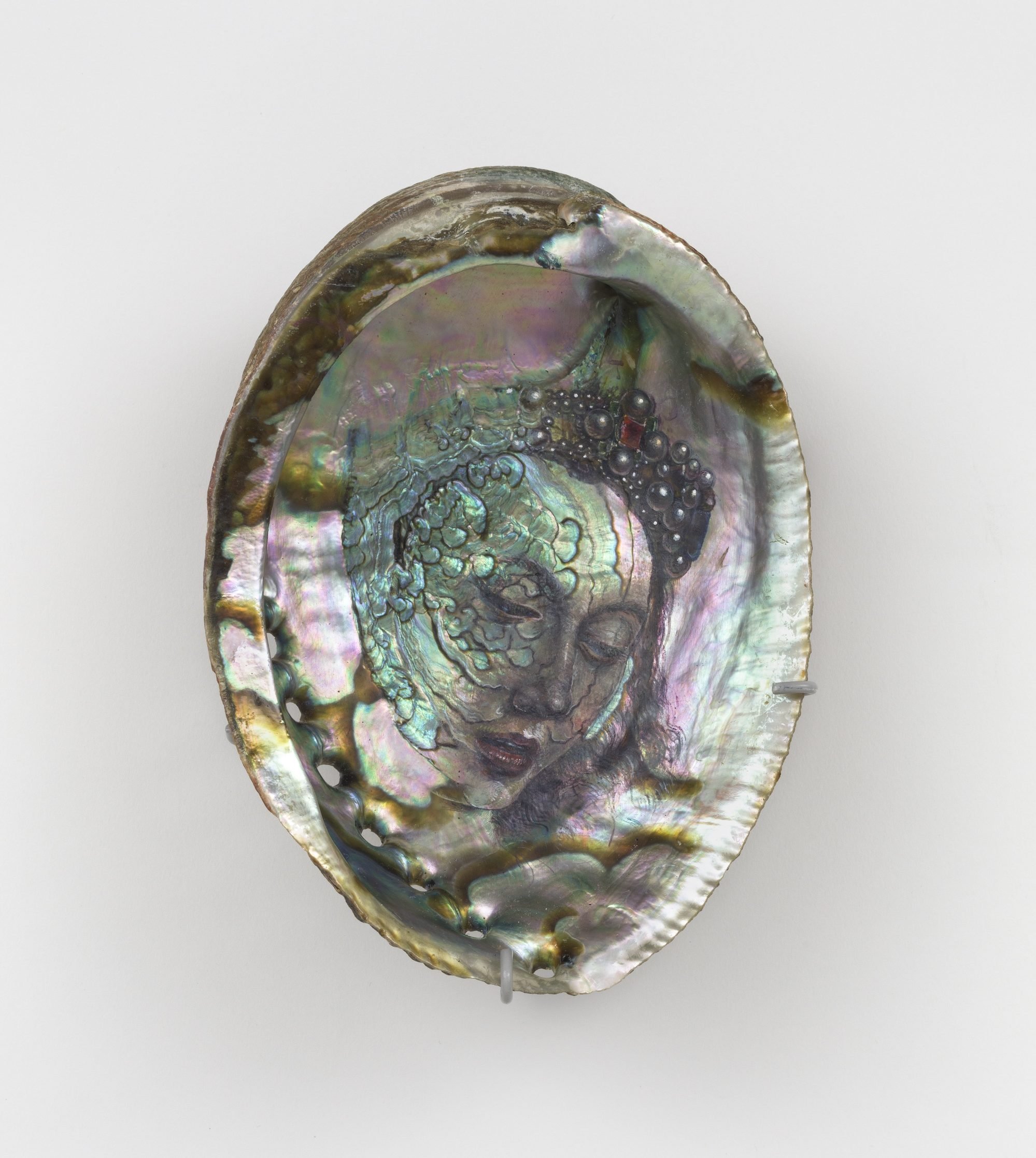

Chris Oh, Tides (2023). Courtesy of the artist and the Institut de la quinzaine.

Weeping Madonnas materialize, seemingly miraculously, on shimmering geodes and pearly shells. Da Vinci designs extend over the sheets and pillowcases. Landscapes hover at the outposts of a pile of worn books. His unlikely pairings are both recognizable and confusing. In a recent book, chasm, the face of the Virgin Mary appears to emerge from within a rock form itself, rather than being painted on it.

For Oh, channeling these age-old paintings into new forms is a lesson in subject matter that transcends time and place. “The emotional interaction with my work is something I think about a lot. I observe what draws me to, say, a Renaissance painting that still speaks to me,” he explained. “The images of grief and pain last a long time, but so does the beauty of love. Beauty endures.

Over the past few years, Oh’s captivating work has captured the attention of a number of galleries. Currently his work is included in “Snakes in the Grass”, a group exhibition at the Newchild Gallery in Antwerp. Works are also scheduled for exhibitions at the Arusha Gallery in London in August and at Blum & Poe in September. In November, he will open a solo exhibition with Capsule Shanghai, his first in China, followed by his second solo exhibition with the Fortnight Institute in New York in early 2024.

Currently, Oh paints from an office he set up at his mother’s house in Portland. Although there is a lot to do, he resists getting carried away. “Life is so unexpected,” he laughed. “I’m lucky to do what I love, but I try to keep the balance. As I get older, I want to stay healthy and have a good day most of the time. It is also important.

Chris Oh, Manuscript (2021). Courtesy of the artist and the Institut de la quinzaine.

Oh, a 2004 graduate of the School of Visual Arts in New York, learned the art of patience. Gifted with a fluid technique, he nevertheless has difficulty identifying his voice. “After school, I stayed in New York doing lots of different odd jobs like a lot of artists do. I didn’t know what to paint for a long time,” he said. “Sometimes boundaries can guide you, but I’ve always been good at copying things, which in some ways meant I had a lot of different choices as to which direction to go. And I just stalled.”

Eventually, he began to piece together pieces of ephemera, sci-fi imagery, and book covers into his compositions in ways that felt meaningful. Yet he found the rectangle of the canvas oddly confined. One day he decided to copy a Da Vinci print he had in his studio onto an Ikea tea towel. “I needed to work on my courage,” he said. “The napkin was still a rectangle, but it had no structure. It opened up this whole new realm of possibilities.

After this, the artist began to roam his apartment and studio in search of objects to paint on, noting a tendency towards “hoarding”. “The objects became almost a portrait of my life, and I was reminded of where I was when I found rubble,” he recalls.

Chris Oh, chasm (2022). Courtesy of the artist and the Institut de la quinzaine.

Oh”‘s first solo showPiecesat the Fortnight Institute in New York in 2016 brought together many of these works, which showcased both the breadth of his materials as well as his art historical lexicon, with references to Leonardo da Vinci, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Caravaggio, Gustave Courbet and ancient Egyptian mummy portraits, plus many more.

“I learned a lot from this show,” Oh said. “I realized what appealed to me a lot was details of the Flemish Primitives of the Northern Renaissance. I didn’t really know many of these artists beyond Van Eyck and Bruegel, but I discovered that I wanted to be exposed to even more of this rich history.

In particular, he was drawn to the paintings’ juxtaposition of intensive detail with slightly wobbly perspectives. “TA camera obscura wasn’t as widely used as it was in the 16th century, so the images are very sophisticated and elegant in their rendering, but there’s this sense of weirdness. It’s very familiar, but something is wrong,” he explained. “It’s also what I look for in my work. This revelation of transformation is what excites me. In some ways, Oh’s materials play with perspective drawn from the painterly tricks of the Old Masters themselves. We think of anamorphic skull on the floor of Hans Holbein Two ambassadors or the revealing mirror on the back wall by Jan Van Eyck Arnolfini P.trait.

Chris Oh, Creek (2022). Courtesy of the artist and the Institut de la quinzaine.

While today’s questions of appropriation and authorship could be traced back to Warhol or Sherry Levine, Oh is, after all, finding a connection to historical traditions of knowledge transmission.

“These traditions go beyond European painting. In many different cultures, people have copied themes and designs as a means of transmitting knowledge. We happen to live in a Eurocentric world, so there are a lot of great books on Renaissance art,” he explained. “Artists copied each other to learn and share. People weren’t sending pictures and texting. These interests sometimes lead the artist to delve deeply into Renaissance bibliographies or copies. “Bruegel gave his cartoons and drawings to his son, who had this whole career based on his father’s work,” he explained enthusiastically. “The work of Rogier van der Weyden engaged in the Italian Renaissance through copies.”

The copies were a way for knowledge to survive the disaster. “Much of human culture that we know of only through copies, as the originals have been destroyed. Many of the paintings I draw from are by unknown artists,” he said. “The Renaissance itself was a celebration of a past culture that might otherwise have been lost to us.”

These works, which so often combine religious imagery and the solid materials of rock and minerals, also go beyond that, asking existential questions about humanity and our relationship to the world around us. “A shell, a piece of wood, a crystal or an architectural salvage – these materials take into account our relationship with nature and how we connect with it,” he said.

“Over the centuries, what remains? Stone objects, buried underground, or in a church, temple or cemetery. They are objects of devotion where humans have contemplated the nature of the soul and the mysteries of human existence, the fundamental question: Why are we here? says Oh. “I try to make relics, in a way, objects that exist outside the boundaries of a certain period of time, that have survived on and in the earth.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.