They are called the Bloodlands, these countries that stretch from the Baltic to the north of Romania. The famous book of the same title by Timothy D. Snyder estimates that around 14 million civilians died there at the hands of Hitler and Stalin, but also the local population, the West being barely aware of what was happening there. passed. Then those same lands disappeared behind the iron curtain for nearly half a century, but now history has returned with a vengeance.

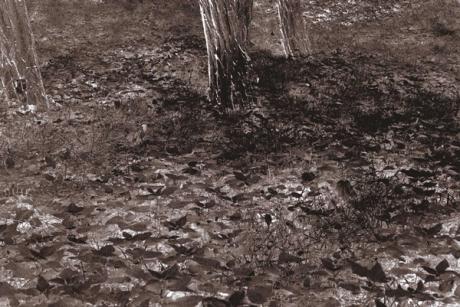

The photographs taken circa 1990 by Judy Glickman Lauder of Nazi extermination sites, still without human beings, are deeply disturbing in themselves and for how they have become relevant to us today. Often she uses the challenging medium of infrared photography which shows white as black and black as white, creating an image like a ghostly memory that looks more real than a conventional photograph.

It is not for nothing that his book of these photos, beyond the shadows (Aperture 2018), quote Solomon bar Simeon, who wrote, “Why didn’t the skies darken and the stars retain their brilliance? Why didn’t the sun and the moon turn black? after the massacre of the Jews of Mainz in 1096.

“These places are a kind of presence but also the absence of what was there”, says Glickman Lauder. The arts journal. “For three years, I went back and forth: so many camps, so many train stations, ghettos, synagogues and towns once populated by Jews that no longer exist. His family was all from that area. “My grandmother came to America, probably in the late 1880s. She had a twin sister in kyiv, who was killed at Babyn Yar [the massacre outside Kyiv of more than 100,000 Jews and non-Jews by the Nazis]. It became a kind of mission for me. I had a lot of exhibitions because I felt people needed to see, because it’s not just the Nazis. Since World War II there have been many holocausts and a lot of ethnic cleansing and this is happening right now. It’s us human beings. We need to be aware of evil, of man’s inhumanity to man, and that we can make a difference, with photography playing a part.

Born in 1938, Glickman Lauder is one of America’s top photographers today, with works in more than 20 museums, including the J. Paul Getty and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She grew up in California, learning first from her father, who was a doctor but also an award-winning photographer with a dark room at home. She still develops her own images and likes to rediscover old techniques such as solarization, cyanotypes and daguerreotypes, but she is not a purist. About the AI-generated images, she says, “Everyone has the right to do whatever they want, even if it’s not my preference or my era. It’s all in the eye of the beholder and the art is totally subjective.

From the age of 20, she always had a camera on her and also started collecting. She has just donated 700 exceptional photos from this collection to the Portland Museum of Art in Maine. Some are very famous, like the 1986 image by Sebastião Salgado of the Brazilian gold mine, with hundreds of men emerging from a vast hole in the ground, or the 1945 image by Henri Cartier-Bresson of the woman whistleblower confronted with an accusing ferment. Many show the cruel side of humanity and the fight for racial justice, as Glickman Lauder has a strong social conscience (she and her husband, Leonard Lauder, co-heir to the cosmetics fortune, gave generously to the academic, medical and museum). Almost all of the images are of people, often in a melancholy vein, like Marilyn Monroe’s 1957 Avedon, still glamorous but with the desperate expression of a lost child. Most are black and white and many are beautiful. Last year, Aperture published a selection of them in a book called Presenceand the collection has toured American museums since then, with the next exhibition at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach running from December 2, 2023 to March 10, 2024.

In the meantime, she has moved on to color with her latest works. “I try to capture the shadow of the palm trees on the grass,” she says, a purely aesthetic challenge she can feel is all that’s left in the face of so much horror returning to the part of the world that she photographed as a warning 30 years ago.