Now that the long-awaited “Afrofuturism” is open at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, we caught up with curator Kevin Strait to talk about the years of planning, the end result, and some of his favorite things about the show.

To begin with, Strait described Afrofuturism as an evolving concept. The term itself was coined by cultural critic Mark Dery in 1993 and was originally coined during his discussions with authors Samuel Delany and Greg Tate, and sociologist Tricia Rose, Strait said. A few years later, researcher Alondra Nelson and others created a mailing list (functionally, a mailing list) to gather voices and ideas about this relatively new scientific term.

“In the early days of the Internet, this mailing list functioned as a virtual community for scholars, musicians, artists, and other like-minded people to discuss and develop the language of this conceptual model that examined the ways in which race, technology and fantasy blend in the creative works and radical expression of African Americans and Black people across the diaspora,” Strait said.

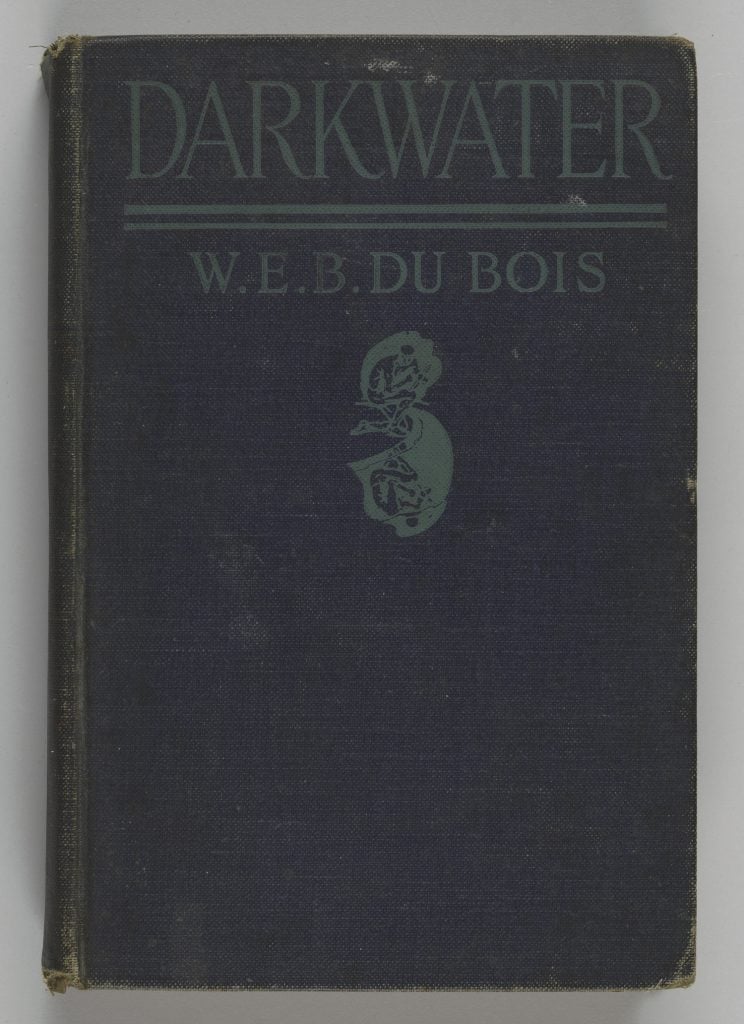

The Smithsonian exhibit traces this history beginning with the cultural roots of Afrofuturism and its African legacies, before moving to the narrative works of slavery and the 20th century with the words and visual data produced by the African-American sociologist and theorist. WEB DuBois.

“Having grounded the concept historically, the exhibition explores the scope of Afrofuturism in the 20th and 21st centuries, exposing the evolving worlds of science fiction writing, fashion, visual culture, film and activism,” Strait explained. “We also explore the central role of music as the primary spokesperson for Afrofuturist expression in art and closely examine its evolution beginning with Sun Ra and continuing with artists as diverse as Lee Scratch Perry, Outkast, Janelle Monae, Herbie Hancock and so many more.

View of the ‘Afrofuturism’ installation at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

When asked how and when he first conceived of the exhibit, Strait told Artnet News that he began writing the script for the exhibit in 2018 and working with the museum on the project. in 2019.

“But I started thinking about Afrofuturism in relation to material culture after our museum took over the Parliament-Funkadelic Mothership in 2011,” he added. “This object carries so much history, and alongside its legacy as an iconic stage prop, it also embodies deep symbolic meaning as a figurative vessel, designed to free the minds of the audience. From these objects , we can see how the themes of freedom and agency are intrinsically woven into their history.After opening our doors in 2016, we have developed several exhibitions that delve into various topics that examine the cultural history of the African American experience.

Asked about the challenges of organizing the show and why the concept is particularly resonant at the moment, Strait pointed to “the inherent complexity that accompanies any exhibition that focuses on identity, representation and contextualization of experience. African-American through a cultural lens”.

Although Afrofuturism has a broad scope that spans generations and of course looks to the future, he said the challenge also provides the museum with an opportunity to examine a wide variety of objects in its collection, linking stories across multiple genres. and disciplines of yesterday and today.

“As the term and concept become more noticeable and part of our daily lives, we see more examples of its impact and influence in our culture. This is the power of social media and our connected lives, where previously siled academic terms like Afrofuturism have now entered our national discourse,” Strait said. “I think the success of films like Black Panther helped cement the ideas of Afrofuturism in our culture. The success of this film is due, in part, to greater public awareness of Afrofuturism and more public demand for stories with black characters, black settings, and black worlds developed by black creators.

Asked what he considers to be among the show’s major achievements, Strait told Artnet News, “I’m glad we’ve developed a narrative that explores the broad history of Afrofuturism expression and connects its story to real people.” For example, the exhibition explores how Nichelle Nichols’ portrayal of Uhura on star trek impacted the recruitment of black people into NASA, as well as how Trayvon Martin’s dreams of working in aviation connect themes of Afrofuturism to real people.

“We also want the exhibit to connect and add another layer of understanding to our museum’s central narrative of ‘out of nowhere’, exploring these new concepts and spaces of identity for African Americans that are emerging over time. time.”

Here are some of the highlights from the show, some picked by Strait.

Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil by WEB Du Bois (1920). Detroit says Du Bois’s The Comet “a wonderful example of speculative fiction that provides an allegory about race in America.” Photo courtesy of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Octavia Butler typewriter, once owned and used by the writer in the mid to late 1970s. On loan from the Anacostia Community Museum.

Costume worn by Bernie Worell of Parliament-Funkadelic, “who created their space-age sound with his innovative use of synthesizers in popular music” (circa 1966). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Gift of Judie Worrell and Bassl Worrell.

ESP custom electric guitar owned by Vernon Reid, “used in recording and video for [Living Color’s] breakthrough song, ‘Cult of Personality’” (1985-86). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Offered by Vernon Reid.

Costume worn by Nona Hendryx from Labelle (1975). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Gift of Nona Hendryx de Labelle.

Cape and jumpsuit worn by André De Shields as a Magician in The genius—the “super soul musical”—on Broadway (1975). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Cap: Gift of the Black Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Jumpsuit and accessories: Donated by André De Shields.

Cape and jumpsuit worn by André De Shields as a Magician in The genius—the “super soul musical”—on Broadway (1975). Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Cap: Gift of the Black Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Jumpsuit and accessories: Donated by André De Shields.

![[The Georgia Negro] Occupations of Negroes and Whites in Georgia ca. 1890. Image courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2023/04/AF-georgia-811x1024.jpg)

[The Georgia Negro] Occupations of Negroes and Whites in Georgia ca. 1890. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

“Afrofuturism» is on view at Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 1400 Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC until March 24, 2024.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.