Everyone is now talking about generative AI and the “Art of AI”, about the dawn of a new era of creative AI that will take the work of artists. We are seeing a huge reaction from artists and the artistic community. Yet the truth is quite the opposite: the era of “AI art” may already be over.

What exactly happened? To begin, let me clarify what I mean by “AI Art”.

AI does not make art; it makes pictures. What makes these generated images artistic are the human artists behind the AI – the artists who fed the machine data, played with its buttons, and curated the output. So I use the term “AI Art” to talk about human art that uses AI as part of the creative process, with varying degrees of autonomy. We are entering an era of massive use of such tools. However, the days when these tools ignited a spark of artistic genius may be behind us.

What makes this spark in art? When Picasso Painted The Ladies of Avignon in 1907, he caused controversy, rejected by his close entourage. Even George Braque, Picasso’s colleague in cubism, did not like him. It was not until 1939, when the painting was exhibited at MoMA, that it was accepted and recognized by the public as a herald of Cubism. jonathan jones written in The Guardian on the occasion of its centenary: “The works of art end up settling, becoming respectable. But, 100 years later, Picasso is still so new, so unsettling, it would be an insult to call it a masterpiece.

by Picasso The Ladies of Avignon (1907) exhibited at the MoMA in New York. Photo: Stan Honda/AFP via Getty Images.

The role of unsettling challenge in the evolution of art can be well explained by a theory in the psychology of aesthetics pioneered by Colin Martindale in his 1990 book, The mechanical muse. He suggested that the main force behind the evolution of art is that artists innovate to combat habituation. However, if artists innovate too much, their art will be too shocking and the audience will not like it. Good artists are those who find that happy medium between being innovative but not too shocking. Great artists are those who push further.

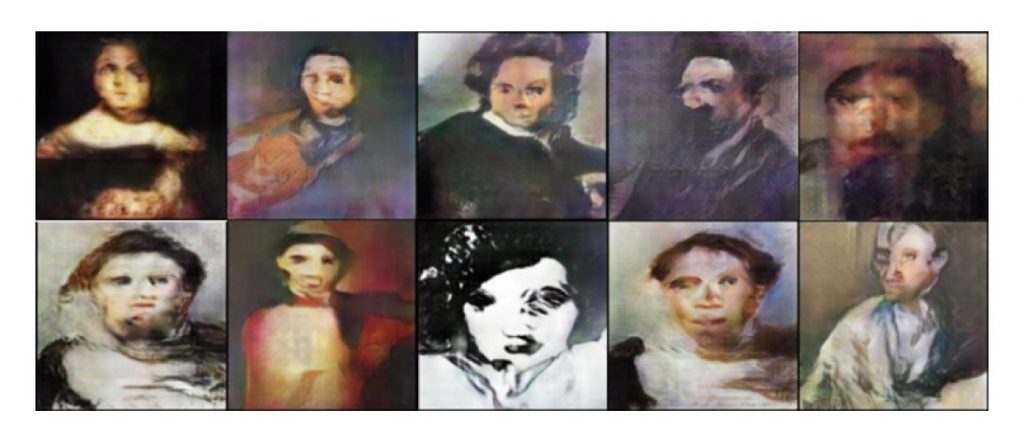

Can AI go beyond good to great? When Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) emerged, some artists took notice of this new AI technology. You can train these models on many images and they can generate new images for you. In 2017, when we formed a GAN on classic portraits in Western art, he created disturbing and distorted portraits, which reminded me of the portraits of Henreitta Moraes by Francis Bacon in 1963. However, there is a fundamental difference: Bacon intended to distort his portrait, while the AI simply failed to make a portrait as instructed.

Francis Bacon, Three studies for the portrait of Henrietta Moraes, (1963). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

With the GANs, we have entered the era of machine failure aesthetics. Some reviewers have linked this to glitch art. Indeed, the surprise of the GAN generations made them intriguing for artists. Many in the area called it the “strange valley”.

It’s this weird vale and serendipity that made AI art interesting between 2017 and 2020. In 2019 I made a study, with art historian Marian Mazzone, where we interviewed several artists who pioneered the use of AI in their process. We found that “artists view AI as a major driver of their own creative processes.” In particular, artists have found AI useful in two ways: creative inspiration And creative volume. This creative inspiration has been where artists have found AI to spark new ideas, new directions, new ways to create their art.

AI portraits generated by a GAN trained on classic portraits, 2017. Photo: Ahmed Elgammal.

Unlike the current backlash climate, AI Art has been well received in the art world between 2017 and 2020.

In October 2018, Christie’s auctioned an AI portrait generated by the GANsimilar to the distorted portraits mentioned above. Sotheby’s has auctioned off a piece by artist Mario Klingemann in March 2019. Manhattan’s HG Contemporary had an exhibition showing my own work in February 2019. The Barbican Center in London exhibited various AI artists in the summer of 2019. AI art was hosted at Scope Miami 2018 and Scope New York in 2019, among others art fairs. The National Museum of China in Beijing is holding a month-long AI art exhibition in November 2019, which attracted one million visitors.

Meanwhile, the media was covering AI art favorably. The art market welcomed AI artists. There have been no calls to ban it. So what happened?

Mario Klingman, Memories of passers-by I (2018). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

A fundamental difference between early AI models and current prompt-based models is that earlier models could be trained on smaller sets of images. This allowed artists to train their own AI models based on their own visual references. Models based on today’s prompts are pre-trained on billions of images taken from the internet without the consent of the artist. This comes with a lot of copyright issues. These massive systems erase the identity of the artist. The difference between my work and your work only depends on the keywords we used in the prompt to drive the system. No wonder the copyright office refuses to protect art generated by such systems. Entering the identity of the artist was the main reason photography could be copyrighted in court in the late 19th century.

In recent years, AI has improved to generate good quality images and photorealistic images. It also improves to mimic the data it is trained on. A new way of interacting has been introduced, primarily using text prompts to control the build. Nowadays, the text prompt has become the dominant way to generate images with AI. These advances in generative AI have made the AI very efficient at following our instructions in a carefully crafted text prompt to generate the image. image we want, be it a photograph or an illustration, in any genre. The surprise is limited to the variations of our idea that we could obtain. With many iterations, we can get the stunning, high-fidelity, high-resolution image we want.

Text promotion helped the AI out of the strange valley. But it killed the surprise. Indeed, these models are trained on both text and images and learn to correlate visual concepts with language semantics. This makes models more adept at creating figures and imitating styles that can be described in words.

Refik Anadol, Not monitored (2022). Courtesy of MoMA.

But, on the other hand, the use of language in training makes the model very limited in creating inspiring visual distortions. AI now creates its visual output confined by our language, losing its freedom to visually manipulate pixels freely without dithering from human semantics.

In a sense, the AI is becoming more like us, unable to see the world with an eye that complements or challenges us.

Naturally, the AI still makes surprising failures in the generation. We always get figures with four-fingered hands and three legs. However, these types of silly failures are not necessarily interesting. It’s not the kind of failure that caused the weird aesthetics of earlier generative AI. Creative inspiration isn’t the only thing lost in this next generation of text prompt-based AI models. The main idea of using text to generate images can limit artists. Artists are visual thinkers. Describing what they want using words adds an unnatural extra layer of linguistic abstraction.

AI is becoming a tool for mass image generation, not the exciting co-creative partner that excites artists with new ideas. The AI is getting really good at following the rules, but the artistic spark in it has gone. Artists will have to dig deeper, go beyond prompts, and use AI differently to find it.

Ahmed Elgammal is an artificial intelligence researcher, professor, founder and director of the Rutgers Art and Artificial Intelligence Lab. He developed AICAN, an autonomous AI artist and the first AI art generator, and founded form of playa platform that allows artists to integrate AI into their creative processes.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.