It’s an art lover’s favorite fun fact: the paintings that hang in the Guggenheim aren’t flush with the museum’s sloping walls and floor. In truth, they are mounted at odd angles that only make visitors look square.

A similar irony permeates Sarah Sze’s new solo exhibition at the museum, “Time lapse.” Throughout the artist’s installations are various measuring instruments that we rely on for order in an otherwise orderless world: rulers, clocks, metronomes. But in Sze’s hands, they serve an opposite purpose, only reminding us of their own futility.

“Measuring tools” are just one of many classes of materials in Sze’s work, who brings an anything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to art, erecting elaborate sculptures from the most more forgettable: wires, stones and lamps. and clamps. It is an art of thing.

As I walked through the exhibition, I found myself unconsciously cataloging all these little everyday objects that the artist used. Entire pages of my notebook are filled with passages like this: “Mirrors, salt, toothpicks, iPhone chargers, over-the-counter pills.”

The impetus came from a desire to break down Sze’s ultra-complicated installations and identify, within their constituent elements, hidden layers of symbolic value. Why did she choose that empty water bottle? What is this jar of mayonnaise mean?

What is this pile of junk art?

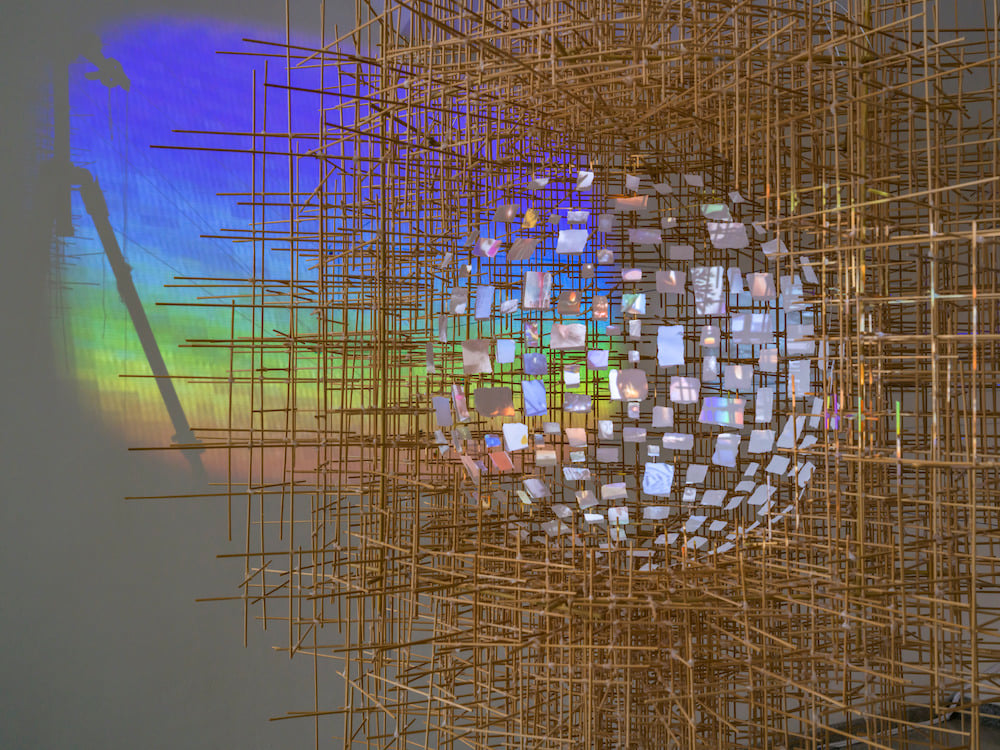

Sarah Sze, Slice (2023), installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Sze, 54, is one of the most successful artists of his generation. Graduated from Yale University, then the New York one school of visual arts, she entered the art world a young star. Her work was included in the 1999 Carnegie International and the 2000 Whitney Biennial. Three years later, she was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship. In 2013, she represented the United States to Venice Biennale. (Sze declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Because of this good faith and his penchant for turning strange spaces into kaleidoscopic spectacles, the artist’s solo show at the Guggenheim arrived with much anticipation. He also arrived late. The exhibit was scheduled to open in October 2020, but was postponed due to the pandemic. Sze, however, made good use of the extra time, periodically visiting the museum to conduct research while it was closed.

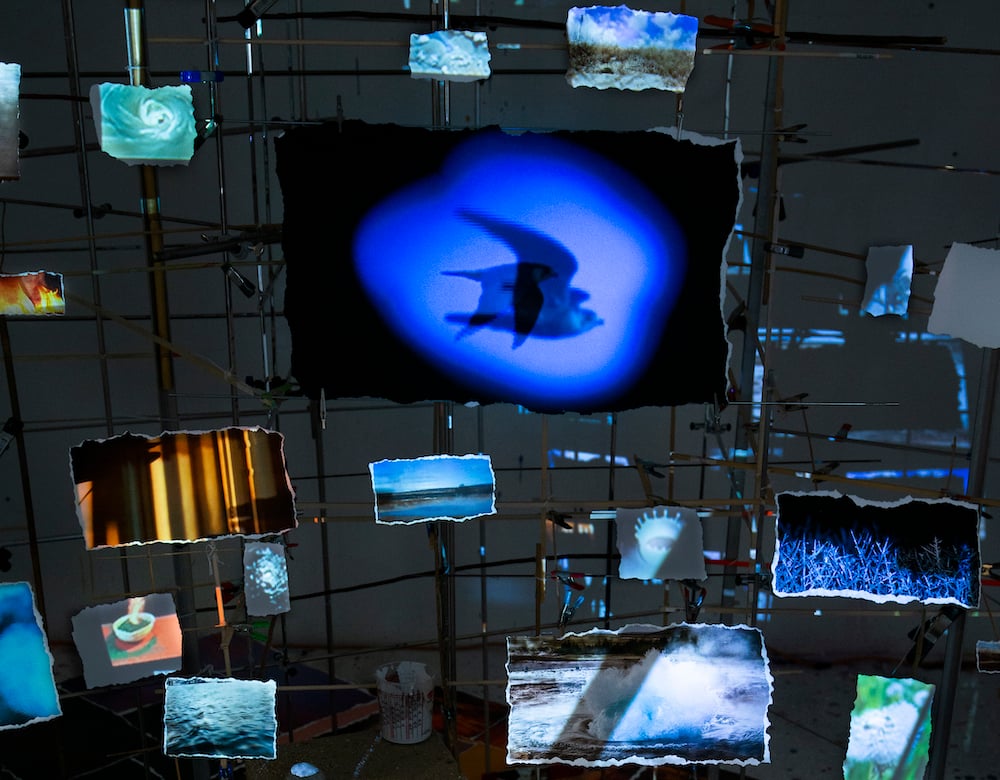

Sarah Sze, Things That Happen (Oculus) (2023), installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

I expected Sze’s works to surpass the Guggenheim as artists like Matthew Barney, Maurizio Cattelan and James Turrell have done in the past. But “Timelapse” is a more modest presentation. It’s largely confined to the top floor of the museum, and even there only some of the bays are truly filled. Instead, most of the artist’s accretions seem to come from the walls of the Guggenheim, like barnacles clinging to a boat. The relationship seems parasitic. (A retrospective dedicated to Venezuelan artist Gego occupies the rest of the museum.)

Some of Sze’s sculptures, such as the imposing scaffolding of sticks and pictures called Slice (2023), take up a lot of space, even if it is often an illusory presence. In works like these, everything is hollow and tenuous, literally held together by glue and string. Part of you wants to blow on them just to see if they’ll fall off.

Sze did not arrive at the museum with these works pre-assembled. Instead, she assembled them on site before opening, an iterative process that took weeks.

“A lot of decisions were made during the installation,” said Kyung An of the Guggenheim, who organized the show. It was during this stage, she added, that “a lot of the elements came to life.”

Sarah Sze, times zero (2023), installation view. Photo: David Heald. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Sze’s sculptures are interrupted by several large-scale paintings, all of which include glued elements. In times zero (2023), for example, a sunset scene is almost obscured by a swirl of photographs fixed to its surface, while other printed fragments are scattered on the ground. At the center of the swirling composition is a low-resolution image of a home, alternately inviting and menacing – a source of heat, perhaps, or a portal to hell.

Another array, called Last print (2023), does something similar, but his own accompanying photos hang before him on a string. Sze punched holes in some of these images, creating small openings through which the painting is constantly cropped and cropped as one passes. “As the exhibit came together, during installation, we realized that each array almost worked like an image-making system in its own right,” An explained.

Tying these systems – and indeed the whole show – together is River of images (2023), a series of traveling digital images and videos that are projected onto artwork, walls, gallery visitors and even the facade of the Guggenheim. Some, like pictures of hands and birds, you’ll recognize from elsewhere in the show; others pass too quickly to register.

This, An said, is “our current reality. We’re just trying to put these things together, all these different and disparate fragmented forms. Sarah talks a lot about how, in our digital world, there’s always a feeling of nostalgia that gets left behind. »

Sarah Sze, Timekeeper (2016). © Sarah Sze. Courtesy of the artist.

The exhibition ends in a dark gallery at the end of the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp, where Sze’s work finally takes over with satisfaction. Featured ago Timekeeper (2016), a sprawling multisensory installation of flashing lights, stuttering gadgets, and other miscellaneous items, including the aforementioned mayonnaise. “Apple, Carabiner, Pellegrino, Foil, Egg,” reads my notebook page from this walkthrough step.

Images are hung, in printed form, on almost every surface, while projectors project others into the room. Most have to do with the very act of making images and its history. There is Harold Edgerton milk drop crown splash (1936), an early example of photography’s ability to capture imperceptible movement, and a shot of a mid-crowd cheetah, reminiscent of the work of Eadweard Muybridge horse in motion (1878). (The famous images of Muybridge, a pioneer of film technology, also appear throughout the show.)

Of all the works by Sze in the exhibition, Timekeeper is the most exciting. It’s no coincidence, he’s also the “junkie” of the band. This is the moment when the artist’s heterogeneous objects transcend their own mixture and merge to overwhelm the viewer with their own excess.

Like the best works of Sze, Timekeeper captures something profound, or profoundly sad, about what it feels like to be alive in the giddy era of late capitalism, awash in images, advertisements, and business solutions that leave us feeling full, but not flourished. Standing in front is like that moment – we’ve all experienced it – when you get to the sixth page of a dissociative Amazon search, a full shopping cart, the only proof of how you got there , and you suddenly become hyper-aware of how little time you have left on Earth.

Sarah Sze, Timekeeper (2016), detail. © Sarah Sze. Courtesy of the artist.

“Sarah Sze: Acceleratedis on view until September 10, 2023 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.