A little less than three years ago, on August 4, 2020, the iconic stained glass windows on the facade of the Sursock Museum in Beirut were shattered after the explosion of several thousand tons of ammonium nitrate in the port of Beirut. As shards of stained glass littered the surrounding area, other parts of the 20ethe architecture of the museum from the last century, reflecting both Venetian and Ottoman stylistic elements, was destroyed. Inside, cherished works of art were damaged and covered in dust.

“It is a miracle that we are reopening,” Karina El Helou, director of the Nicolas Sursock museum, told Artnet News. She was appointed director just over six months ago, taking over from Zeina Arida, who now runs Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar. “We are a society of survivors. We are still in crisis. But what we have to learn today is to look to the future and the museum symbolizes this.

Like hundreds of other buildings in Beirut, the Sursock Museum, Lebanon’s oldest independent cultural establishment and one of the first museums in the Middle East to celebrate modern art, was a ghost of itself.

The first and second floors of the building suffered the most damage from the explosion. The facade of the Sursock Museum in July 2021. Photo by Rowina Bou Harb. Courtesy of Sursock Museum.

On May 26, amid immense political and economic hardship for the country, the Sursock Museum, seemingly miraculously, reopened, rising from the ashes of the Beirut port explosion.

The museum, with its sleek new exhibition spaces, is a perfect example of the cacophony of struggles and contradictions that characterize daily life in Beirut, where an ongoing financial crisis has pushed three-quarters of the population into the poverty and the government is stuck in a political stalemate.

As in much of Lebanon today – for those who can afford it – the museum operates with the constant drumbeat of generators supplying electricity to its many gallery, library, restaurant and café spaces, since the state provides only two hours of electricity per day.

The Salon Arabe after the explosion. Image taken on August 5, 2020. Photo: Rowina Bou Harb. Courtesy of Sursock Museum.

Meanwhile, outside its gates, street beggars make their rounds amid furious traffic, buildings that still bear scars from the blast stand alongside others that are shiny and new, and the locals wine and dine at a host of new and old restaurants and cafes.

“It was incredibly difficult to rebuild during a time of crisis,” El Helou said. “We kept thinking, ‘Will we have all the gear? Will we finish in time? Technically, we live in a country that has completely collapsed. We don’t have public electricity; we don’t trust our politicians.

“Rebuilding the museum is part of our healing: looking to the future and starting to dream again,” El Helou added. “The museum gives us something to celebrate.”

The Salon Arabe fully restored in April 2023. Photo: Christopher Baaklini. Courtesy of Sursock Museum.

The museum raised a total of $2,376,751 for the effort following the explosion. The French Ministry of Culture and the International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Zones each provided half a million dollars. The Agenzia Italiana Per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo (AICS) in partnership with the UNESCO Campaign – Li Beirut (for Beirut), donated $1 million. Additional funding was obtained from Lebanese and international private donors.

No money or support has been granted by the Lebanese government or the Ministry of Culture.

The restoration included the repair of around 50 works of art, including a portrait of Nicolas Sursock, the Lebanese art collector who died in 1952 and who donated his private villa (built in 1912) in Beirut as a museum, and Untitled (Consolation) by Paul Guiragossian. Both works were restored by a team from the Center Pompidou in Paris.

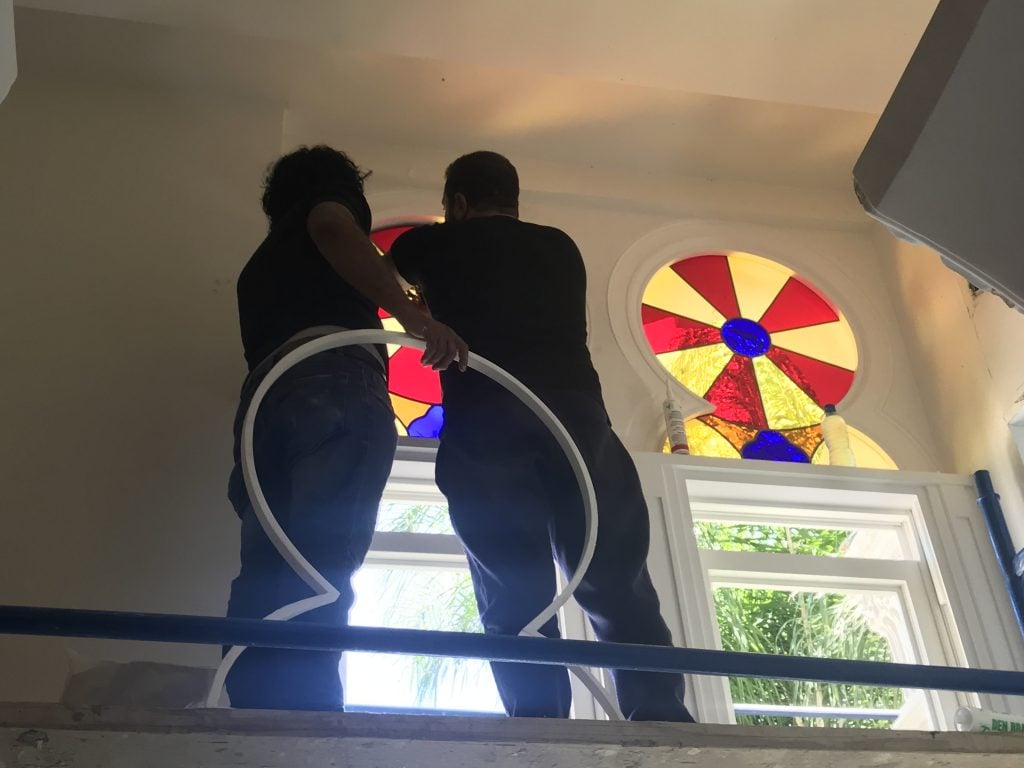

All of the museum’s windows needed to be replaced, along with its elevators, and the interiors repaired, from the doors and ceilings to its electromechanical system. The traditional wooden panels on the historic first floor of the museum, such as those in the Salon Arabe, where Sursock once hosted its guests, also had to be restored.

Installation of stained glass at the Sursock Museum, July 2021. Photo: Rowina Bou Harb. Courtesy of Sursock Museum.

“Our job to rebuild the museum is to help the Sursock serve the community again,” AICS Beirut director Alessandra Piermattei told Artnet News, adding that the Italian government agency has been working in Lebanon for years. 1980. “We want the museum to help people continue their normal lives and to serve as a meeting place for cultural life.”

The Sursock Museum has been a staple of the city’s cultural scene for decades. During the 1960s, he organized an annual Salon d’Automne, an open exhibition that featured works by artists living and working in Lebanon. And among the five exhibitions that the museum has organized for its reopening is “Je Suis Inculte! The Salon d’Automne and the Canon National”, a show that revisits the heritage of this program.

Restoration of the woodwork on the doors of the Sursock Museum, June 2021. Photo: Vicken Avakian. Courtesy of Sursock Museum.

Likewise, “Beyond Ruptures: A Tentative Chronology” explores the history of the museum and the socio-political events it has seen, through works by Lebanese artists such as Jean Khalife, Akrim Zaatari, Aref El-Rayess and Shaffic Abboud. .

There is also a poignant specially commissioned video installation, Ejecta by Zad Moultaka, who recreates the explosion of Beirut through digital images of every artwork in Sursock’s permanent collection.

“We still don’t know the truth behind the explosion – investigations have ceased,” Rana Najjar, a Lebanese media consultant, told Artnet News. But, she added, “The museum heals me. I have so many childhood memories here; it symbolizes the collective memory of the Lebanese people. This is our hope; it is a victory for the people.

More trending stories:

Sculpture depicting King Tut as a black man sparks international outrage

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.