Mosul’s Cultural Museum was targeted and nearly destroyed by the so-called Islamic State (Isis) when the terrorist group took control of the Iraqi city in 2014. Less than a decade later, the partially restored museum has restarted his activities.

This month, the museum hosts the first exhibition of objects from its collection since the attacks. The exhibition will be presented in the recently restored former royal hall adjacent to the site. The museum itself will fully reopen to Mosul residents in 2026 following the completion of an ongoing restoration project. It is rebuilt from the plans of its original architect, Mohamed Makiya, and will feature restored objects from its established collection as well as new finds from archaeological digs in the area.

“I have ordered that all artifacts found during the ongoing excavations in the ancient city of Nineveh should be taken to the museum, not to Baghdad,” said Laith Hussein, head of Iraq’s State Council of Antiquities. and Heritage, the arm of the Ministry of Culture which carries out the project alongside the cultural heritage agency ALIPH, the Louvre Museum, the Smithsonian and the World Monuments Fund. “It is important that the museum receives these pieces,” says Hussein. “That’s where they belong.”

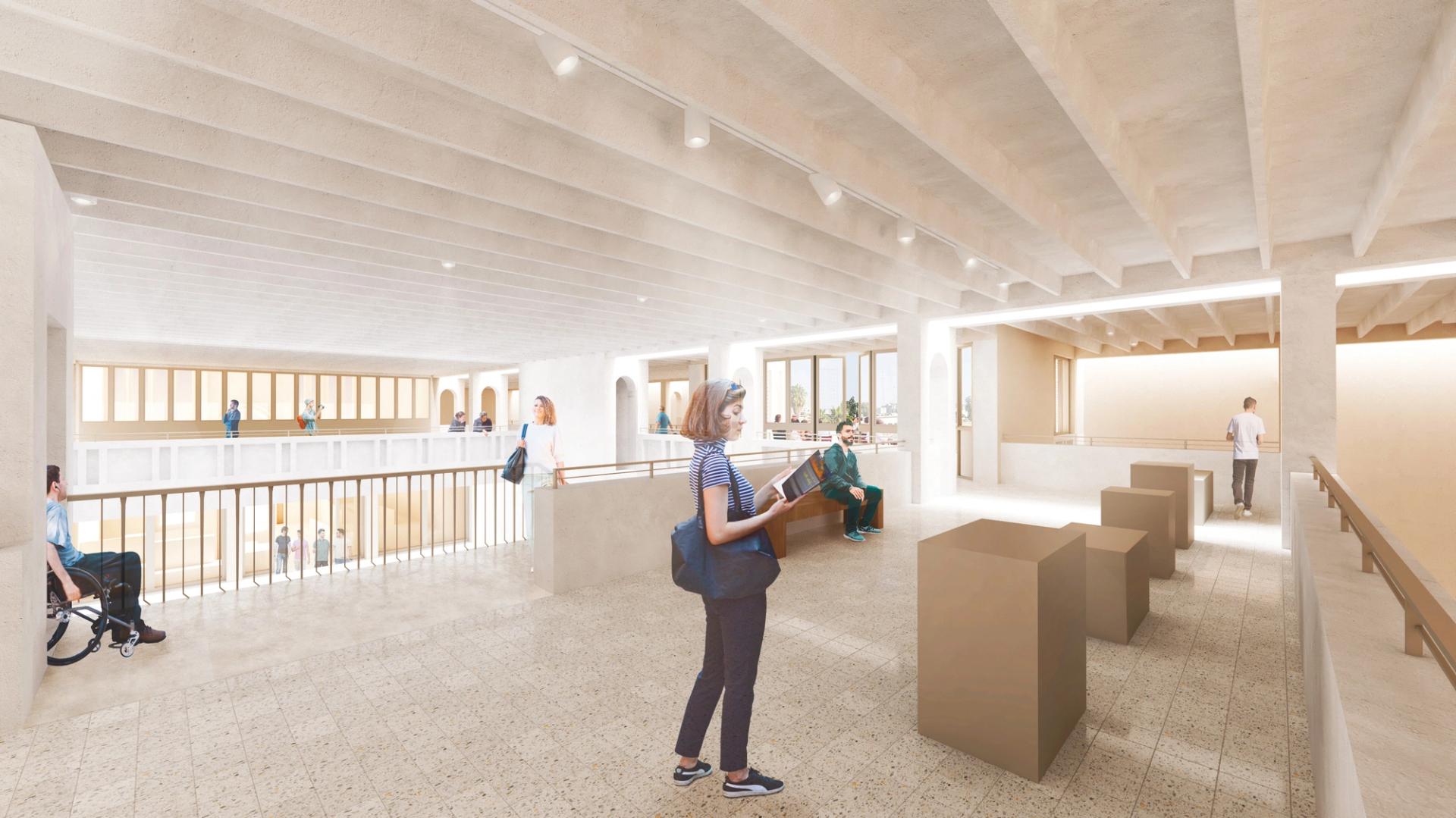

Rendering of the mezzanine floor of the Mosul Cultural Museum, scheduled to reopen in 2026; the restored building follows the plans of the original architect Mohamed Makiya © World Monuments Fund; Donald Insall Associates

This epic rehabilitation of the Mosul museum, the second most important in the country after that of Baghdad, represents a symbolic step forward in the renewal of the city.

Mosul was Isis’ main base in Iraq and the site of its last battle, and was reconquered in a protracted battle with a US-led coalition of forces. The conflict has destroyed much of Mosul’s historic old city. Even today, most of the city’s structures remain shattered, with gaping storefronts, bullet-riddled facades and crumbled multi-story buildings.

The museum itself, in the center of the old town, was hit by shelling, but most of the damage predates the battle and comes from Isis herself. In 2015, supporters of Isis hacked the statuary of the 2nd-century city of Hatra with maces, in a video that remains online. In the museum’s Assyrian Hall, they placed dynamite under a ninth-century BC platform for a throne that was interwoven with intricate cuneiform carvings. The explosion blew up the base of the throne while another explosion took away the other sculptures in the room: two lamassu – the fanciful winged creatures typical of Ayssrian iconography – and a huge lion that once guarded a temple at Nimrud.

“Destruction takes a moment,” says Ariane Thomas, head of the Near East antiquities department at the Louvre, who joined the project in 2019. “But reconstruction can take forever.”

It took a year to clean and correctly identify the rubble on the ground, explains Daniel Ibled, the curator of the Louvre who leads the team of French and Iraqi specialists. Four years later, the base of the throne and lamassu begin to revert to their old forms. But it’s a slow, painstaking process akin to solving a jigsaw puzzle made of crumbling stone.

Balance

Those responsible for restoring the museum sought a balance between remembering the realities of Isis’ occupation and completely modernizing the space. Following consultations with the local citizens of Moslawi, the museum decided to retain the hole that was dug in the floor of the Assyrian Hall during the dynamite explosion of Isis. The hall itself will remain closed to visitors, who will be able to view it from a mezzanine above.

The rehabilitation will also restore Makiya’s original architectural designs. Mosul is Makiya’s only museum in Iraq, where he was known as an important modernist architect and proponent of the artistic flourishing that occurred in Iraq in the 1950s and 1960s. Makiya also co-founded and directed the Al- Wasiti, where artists such as Jawad Salim and Faeq Hassan exhibited their work. He designed many buildings in Iraq and throughout the Gulf, but he couldn’t see the opening of the elegant Assyrian-inspired design he drew for Mosul. When the museum opened in 1974, he had fallen out of favor with the Baathist regime and had to flee Iraq.

The museum has some deviations from the original plans, but experts from the World Monuments Fund, which is overseeing the rehabilitation, say they have not been able to determine whether these have been approved by Makiya. They will, however, reverse changes made to the museum in 2008. Two small balconies on either side of the building have been blocked off to create more gallery space, while open openings in the front facade have been closed. This allowed for more exhibition space by allowing a mezzanine to function as a gallery, but it drastically closed off the light and openness that was a key element of Makiya’s designs.

The contents of the museum, when it opens, will include the objects that have been restored by the Louvre team, new excavations from Nineveh, and a collection of original museum objects that were sent to Baghdad for safekeeping in 2003. Although the destruction of Isis represents the most acute phase of the damage suffered by the museum, it was closed intermittently for 20 years – a dismal demonstration of the length of Iraq’s suffering. Objects that were moved to Baghdad remained in storage, thus avoiding the widespread looting to which the Baghdad museum fell prey. Fortunately, unlike the Baghdad Museum, whose inventory would have been lost, the Mosul Cultural Museum has kept a more complete archive of its collection.

Teams from the museum and the Louvre have worked over the past four years to identify exactly what has been lost, publishing a detailed list of 68 objects in a catalog, on the web and via Interpol, in hopes of recovering any resurfacing artifacts. in private collections or auctions. Although this catalog – which also provides material for the museum’s adjoining exhibition – may seem like a narrow academic achievement, it is in fact a major document that contributes in part to enabling these objects, whether they be looted or destroyed, to live in memory. But it’s also partial: in a fire they started with highly flammable asphalt, Isis also set the museum library on fire with around 25,000 manuscripts. It is likely that other poorly inventoried objects were also lost.

International cooperation

Across Mosul, the scale of international collaborations matches the sense of what has been lost. The city was known for its religious tolerance, with a symbolic “conversation” between the call to prayer of its famous minaret of the Al Nuri Mosque and the bells of the Notre-Dame de l’Heure Church, two towers that dominate the horizon.

Both sites are currently being restored by Unesco (with funds from the United Arab Emirates and ALIPH). ALIPH, which was partly created in response to Isis’ campaign to destroy, works at eight other sites across the city and is piloting the Mosul Museum project.

Although progress is slow, restoration work is underway throughout the old city, both for cultural sites and for everyday dwellings. (I asked a young Moslawi what the local economy was like. He gestured towards the storefronts full of people selling car parts, fridge panels and other dusty items. “Fixing things “, he said.)

But security also seems precarious. The constitution requires equal representation between Shiites and Sunnis, and this balance is generally accepted on the ground. There are a few Isis cells left in very rural areas, but there have been almost no incidents of kidnapping or violence in recent years. Yet the heavy presence of militarized forces and the large number of firearms in daily circulation mean that any new conflict could easily escalate.

The press conference at the Mosul Museum opened with remarks from the Minister of Culture and Hussein, as a sign of the federal government’s commitment. But security was tight: the area was swept twice for bombs and the perimeter was guarded by men armed with AK-47s, which, at the time of the press conference, seemed perfectly normal. My delegation, supported by ALIPH, had spent all our time in federal Iraq under armed protection. A group of Kurdish personnel drove us to Mosul from Erbil in armored cars, our dog handlers stopping to put on body armor and pull out guns after passing the checkpoint into Federal Iraq.

The future of the Mosul Museum, and of Mosul as a whole, cannot be taken for granted. Nonetheless, local residents are now discussing the benefits of cultural tourism and a diverse economy, but these things will only happen if those with the resources act as if they will.