Artist Tara Geer, known for her raw, almost sculptural charcoal drawings, is on a roll this year. His large-scale works were the subject of a captivating exhibition at the Guild Gallery in downtown New York last spring, titled “Unstill World” (April 20-May 27), juxtaposed with sculptural creations by four Japanese fiber artists strategically placed in the gallery.

On July 22, the Arts Center at Duck Creek— a 19th-century barn in East Hampton — will open “Tara Geer: Sown in Half-Light,” an exhibition of large drawings (through Aug. 20) that features a mix of unusual bulbs, stems and wildly paneled scribbled. This is the first large-scale public installation of his work.

Geer counts a wide range of styles as influences, ranging from traditional Chinese landscape painting and ancient Japanese calligraphy to Mexican “retablos,” small, colorful paintings usually executed on pewter. She has been a teacher in the Arts and Arts Education Program at Teachers College, Columbia University for the past three decades, while continuing to draw her charcoals.

Geer’s works are held in several museums and public collections, including the Morgan Library & Museum, the Parrish Museum, and the William Louis Dreyfus Foundation, among others. Her work with the six-woman activist collective Victory Garden can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the New York Historical Society, the Beinecke Library at Yale University, and the Canadian Museum. After a recent Guild Gallery exhibition preview with the artist, we caught up with her for a virtual tour of her West Harlem studio on the eve of the new exhibition.

Artist Tara Geer at work. Photo: Fredrika Stjarne.

Tell us about your workshop. Where is it, how did you find it, what type of space is it?

After graduating from Columbia University’s School of the Arts in the late 1990s, myself and a few adjunct professors signed a lease for the third floor of a dilapidated building in West Harlem, a block from Hudson River houses. It was beside the freeway, in the shadow of the massive metal frame of the elevated section of Riverside Drive, an area with no visible nature except for the flat, gray course of the river. The previous tenant was an accessories company. We kept a three-foot saw blade on which someone had painted ‘chickens for sale’ and subdivided the floor into eight studios. At that time, the building was surrounded by slaughterhouses, storage, abandoned buildings and a Cleantex laundry. I’ve been on the same floor for nearly 25 years, climbing the same three flights of uneven stairs and listening to the sounds of the city change. I still feel the wave of happiness starting from the first staircase. Now two very popular clubs below me play music on the weekends, bouncers look at my clothes and look away. I have 15 foot ceilings, a skylight, two large south facing windows over a city bus parking lot, a huge space above parked buses and a sky above buildings. When I close the door to my studio behind me, the peace and quiet of the pool surrounds me. I love my workshop.

Photo by Fredrika Stjärne

Do you have studio assistants or other team members working with you? What are they doing?

The first 10 years I had a studio that I hardly let anyone in, ever. I wanted to be alone, to feel alone, to hear my own voice, not to try to do anything for anyone but myself, to be able to do ridiculous things, or crazy mistakes and not judge them, to know what I thought of it.

The closing of a door on a space in which you don’t have to be someone, or anything, or please anyone, or clean, or do an assigned job, or be nice, or smile and you asking if you are doing the right thing is profound and powerful. We become artists, in some cases like mine, because we can’t stop. And no one else can tell you how to do it.

Photo by Fredrika Stjärne

The studio is where I learn to be an artist – not what it’s supposed to look like on the outside with cool outfits and hair at a vernissage, but what it really is. When I felt like I had learned to draw on my own, after a decade, I started letting in people I looked up to, maybe one or two a year. It was more difficult for me to acquire the skills necessary to be an outward-looking artist than the work of making art, by myself in my studio. I had to learn to open the door of the outside world. Last year, I had a kind of studio assistant, a few half days, a few months, then I worked with an archivist. Most of the time I do the work myself. I like to work alone.

How many hours do you typically spend in the studio, what time of day do you feel most productive, and what activities take up the majority of that time?

Before I had kids, when I didn’t have to work, I worked in the studio all night. After the birth of my first child, I no longer had that kind of time. I decided that I had to remove all watching and considering. Any idea that popped into my head, I did. If I was thinking, maybe rip the middle, I would immediately rip the middle. I didn’t spend time weighing whether it was a good or a bad idea. I have even more time now, with kids at school, but I’m still trying to get out the door. It’s more fun. I’m in the studio three to four days and two to three nights a week.

Photo by Fredrika Stjärne

What’s the first thing you do when you walk into your studio (after turning on the lights)?

When I’m in the middle of something, I put on my studio clothes, turn on the kettle and get absorbed in the drawing as the kettle starts to whistle, and I don’t bother to make the tea. The rest of the world falls. This part is hard to describe. Joy maybe. I’m sitting in front of a big, ugly, water-swollen desk and I can feel the partial drawings, or the empty walls, breathing behind my back. I thought that with experience I would learn to work easily, evenly, regularly. It turns out, on the contrary, that it is part of this life, to enter and leave the garden of my own work. And even in the studio, with time ahead of me, I can stand in front of the door and wonder how to get back.

Image courtesy Tara Geer

What tool or art supply do you most enjoy working with, and why? Please send us a picture of it.

I love my electric pencil sharpener. I flatten out hundreds of pencils a day, bowls of them. The sharpener saves me time that I would have to spend scraping them into points with a blade knife. This Afmat makes a beautiful and long remark. Also, if I take the top off and use pliers, I can sharpen my heels much further. One might consider the risk of electrocution, or one might not.

What atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Is there anything you like to listen to/watch/read/watch etc. in the studio to inspire you or as ambient culture?

Sometimes I find that listening to repetitive music without lyrics – or in languages I don’t know – is helpful. Then I get tired and put on whatever makes me want to dance and struggle. When I’m inside a drawing, I don’t hear the music.

Image courtesy Tara Geer.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get out of it?

I tried to normalize this return. For the past few years, when I feel stuck, or even stuck, I circle around. I close my eyes and, as slowly as possible, brush uneven circles of ink, in a likely non-kosher, bogus version of the Zen Buddhist monk practice called Enso. I do the circles over and over again until I’m not looking at the drawing anymore, even in my head. I feel in the world. Then I leave notes under the ink circles on what worked for the next time I get stuck. Sometimes, I say, it’s enough to get your hands dirty for the duration of a good song. Or, feel as crowded as there is room in a tub, then leave.

Where do you get your food from or what do you eat when you’re hungry in the studio?

I have an electric kettle and I turn it on to make tea, then repeatedly forget it. The nearest bodega is a 15 minute walk away so I never go there. I usually try to keep a box of cereal or something I can’t eat with my hands because they’re blackened with charcoal and probably lead dust.

Photo by Fredrika Stjärne

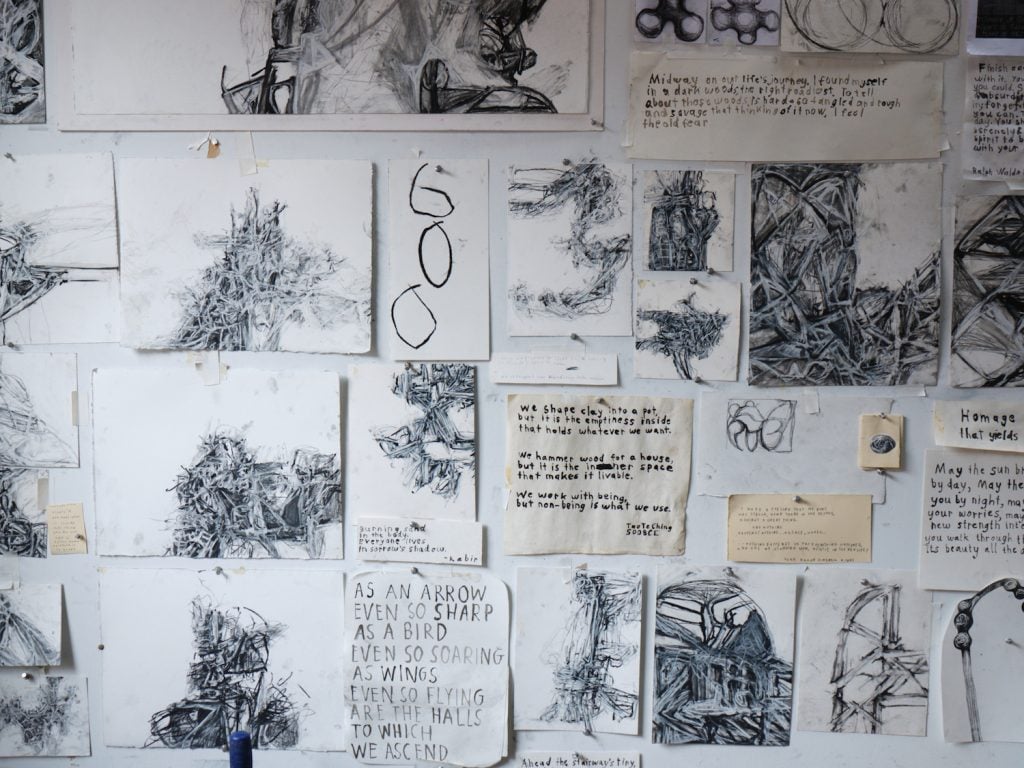

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

It’s dirty. In the film version of an artist’s studio, you have an affair on the couch. My sofa is barely visible under torn parts of charcoal drawings, piles of inked circles on crumpled rice paper, paint stains and dog hair. My dog has been against it for a while. Around the edges of the floor are mounds of gum shavings, charcoal dust and shredded paper, plastic take-out containers of hardened glue and cups of cracked ink. It’s a gift to have a space that can’t be wasted.

What is the most chic object in your studio? The most modest?

My partner put wheels on my work table, so I can move it easily, it’s chic. The rest of the furniture was abandoned when I brought it back.

Describe the space in three adjectives.

Yet dirty, beautiful.

What’s the last thing you do before leaving the studio at the end of the day (other than turning off the lights)?

Wash the charcoal off my face, neck and arms.

What do you like to do right after?

Go home.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.