Deaths of key collectors are propelling scores of blue-chip art to the market.

The Art Detective hears that the $500 million Emily Fisher Landau estate, so far the biggest prize of the upcoming season, will go to Sotheby’s for an auction led by Pablo Picasso’s large-scale 1932 portrait of Marie-Therese Walter. (A Christie’s representative said that the group “is definitely not going to Christie’s as of right now”; Sotheby’s said “there is nothing to share at this time.”)

There’s also the estate of Bay Area art patron Chara Schreyer, with a gorgeous Frank Stella, going under the hammer, as well as a smaller group by postwar masters Willem de Kooning, Richard Diebenkorn, and Franz Kline consigned by San Francisco collector Sanford Robertson in the wake of his wife’s death in 2018.

But one significant collection isn’t heading to auction. The heirs of the financier Thomas H. Lee, who shot himself in February, have decided to sell things privately.

Lee began amassing postwar and contemporary paintings, photographs, sculptures in the 1990s after brilliantly flipping soft-drink company Snapple, which he acquired for about $135 million in 1992 and resold for $1.7 billion two years later. Armed with about $927 million, Lee jumped into the art world as a both a buyer and a philanthropist, frequenting auction salesrooms and joining the Whitney Museum of American Art’s board of trustees (where he served for 29 years).

Thomas H. Lee and Ann Tenenbaum’s Sutton Place apartment photographed during an event in 2019. Works by Ellsworth Kelly, Donald Judd, Mark Rothko, Fred Eversley, and Andy Warhol are on view. Photo by Matteo Prandoni/BFA.com ©BFA 2023.

Canvases by Mark Rothko, Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock, and Francis Bacon hung in the Sutton Place apartment Lee shared with his second wife, Ann Tenenbaum. A monumental 1964 blue-and-red canvas by Ellsworth Kelly was promised as a gift to the Whitney and a collection of photographs to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some of Lee’s most valuable works have been offered for sale privately in recent months, according to dealers, advisers, and auction specialists. The family is said to be working with the art dealer Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, a friend of Tenenbaum’s, as well as the advisers Amy Cappellazzo and Andrew Ruth, the latter of whom had a long working relationship with Lee.

The way the heirs are going about things has puzzled some market onlookers.

“It was an up-for-grabs kind of thing,” said a major art adviser. “And it was confusing to someone like me to be talking to different dealers about the same pictures.”

Bacon’s small Study of Gerard Schurmann was spotted in a private viewing room at LGDR gallery in April, when it opened its new gallery on East 64th Street. Greenberg Rohatyn worked there as the “R” in the title until splitting off last week.

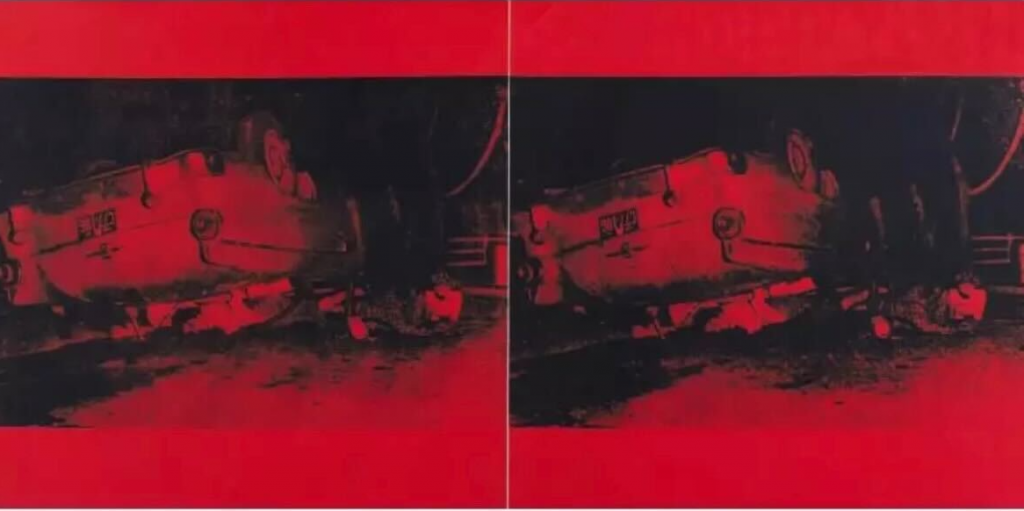

Other works on offer included: Warhol’s 1963 5 Deaths Twice 1 (Red Car Crash), Pollock’s 1949 Number 22, Rothko’s nearly eight-foot-tall Olive Over Red (1956), Jean-Michel Basquiat’s 1982 oilstick drawing, and an untitled 1969 Donald Judd wall piece of brass and aluminum.

Thomas Lee and Ann Tenenbaum in New York City, 2019. (Photo by Mike Coppola/Getty Images for Film at Lincoln Center)

Tenenbaum didn’t respond to the Art Detective’s email seeking comment. A representative said she wasn’t available.

“Tom Lee used leverage as a vehicle,” said a person familiar with her thinking. “And Ann Tenenbaum doesn’t work like that. It makes sense that she would sell the art whether she had to or not.”

She may have decided to try selling art privately to avoid public scrutiny and speculation about the cause of her husband’s suicide, several art world people said.

The auction schedule apparently didn’t work in her favor either, according to the person familiar with her thinking. May was too close and November too far off, the person said.

Meanwhile, the art market has experienced a dramatic shift in real time; prices that seemed reasonable in March suddenly appeared “aspirational,” according to one person who was offered some works but chose not to make any bids.

Word on the street is that works by Pollock (said to be worth about $40 million in March), Warhol (said to be worth $15 million to $20 million in March), and Basquiat (said to be worth about $7 million now) have sold.

Over the years, scores of Lee’s artworks have been listed as collateral for bank loans, according to public filings reviewed by the Art Detective. These documents offer a rare glimpse into his formidable collection—as well as how the sophisticated leveraged-buyout pioneer put it to work for himself as a financial tool.

The earliest available filing dates to 1995 when Lee began borrowing from Citibank, the first financial institution to offer art lending to its ultra-wealthy clients. (The paperwork lists the collateral as “consumer goods, consisting of paintings, drawings, sculpture and other works of art and decorative objects of every kind and nature.”)

Andy Warhol, 5 Deaths twice 1 (Red car crash) (1963). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The timing of the loan suggests, remarkably, that Lee began unlocking value from his art holdings almost immediately after he began collecting.

Later, in 2004, the Citibank filings listed 65 artworks, an impressive group of names ranging from modernists Piet Mondrian, Juan Gris, and Claude Monet to pioneering photographers Edward Weston, Alfred Stieglitz, and Diane Arbus. He had three works by Jasper Johns, four by Lichtenstein, two Pollocks and two Gerhard Richters.

That same year, Lee took a loan from HSBC Bank USA backed by another 54 artworks, mostly on paper, including an etching by Rembrandt, a gouache by Georgia O’Keeffe, the 1982 Basquiat, and a 1971 Cy Twombly.

During the financial crisis of 2008, Lee augmented that line of credit with higher-value works that included Pastorale, a 1963 painting by de Kooning, and the aforementioned 5 Deaths Twice 1 (Red Car Crash) by Warhol and Study of Gerard Schurmann by Bacon.

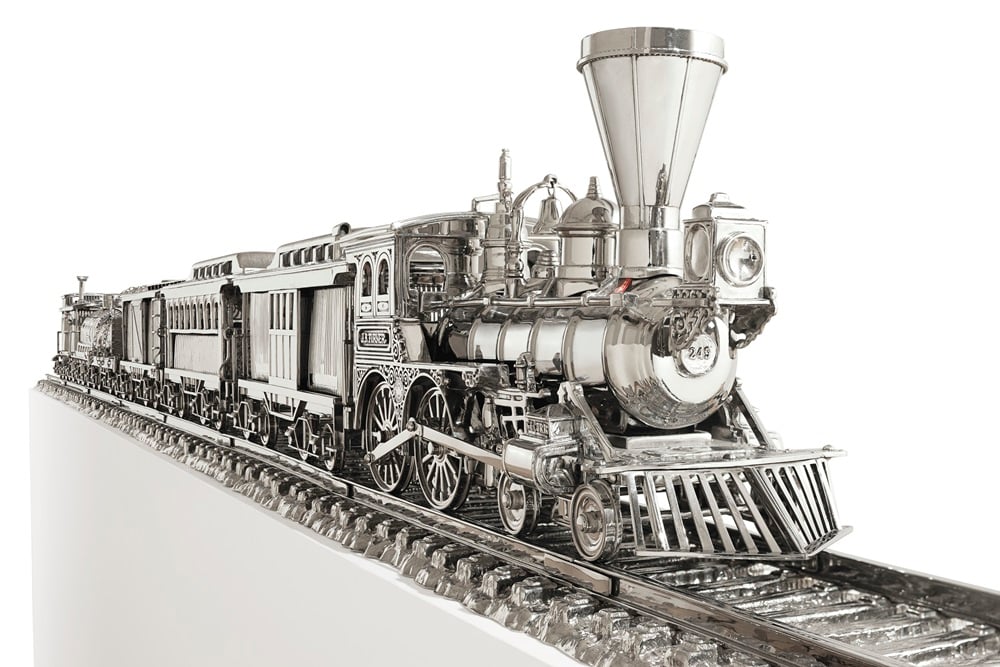

Jeff Koons, Jim Beam – J.B. Turner Train (1986) stainless steel and bourbon. Courtesy: Christies.

Around the same time, the financier also sold art to generate cash, according to the adviser who Lee asked “to take what you want” from the collection. Several works by Lichtenstein, Richter, Koons, and Polke were removed from Lee’s collateral pool in 2008-2009, suggesting they were sold. One of his top pieces was the Jim Beam Turner Train by Koons. At the time, those in the know said that the royal family of Qatar bought the work.

Perhaps the largest deal of this kind came toward the end of Lee’s life, when he got a $100 million loan from Bank of America backed by $200 million worth of art, according to a person familiar with the deal. A representative for Bank of American declined to comment.

Now, the haste to sell off Lee’s art is likely because his heirs want to pay off their debt sooner rather than later due to increased interest rates, which have doubled or even tripled investors’ debt burdens over the past year.

“You pay off a loan when you don’t want to have that much debt,” said the major art adviser. “You want to clean up the balance sheet. It’s good housekeeping.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: