For its second edition, St Louis’s counter public triennial is turned towards the future. With 30 commissions and a curatorial ensemble of six members, counter public examines how a civic exhibit can avoid becoming a spectacle and instead support healing, repatriation and generational change. The ambitious triennial, which runs through July 15, spans a six-mile stretch of Jefferson Avenue. Central themes include the history of displacement and erasure of Indigenous and Black communities in St Louis and the role of the land as a witness and potential vehicle for regeneration.

“We didn’t want the exhibition to just reflect on history or point to other futures without considering the past,” says James McAnally, who co-founded counter public with Lee Broughton. “Instead, Counterpublic sees repair, repatriation and reparation work as a lens to better understand how to respond individually and collectively.” McAnally is one of this year’s curators alongside Allison Glenn, Risa Puleo, Katherine Simóne Reynolds, Diya Vij and the New Red Order collective.

Positioning the exhibit along the central thoroughfare of Jefferson Avenue allowed Counterpublic to cover 13 different neighborhoods. “These neighbors are a primary audience; the exhibition is for them first,” says McAnally. “The orders are part of the regular rhythms of the city. They are there to be experienced and to expand what we know and how we understand St Louis.

Projects related to the past, present and possible futures are most directly related to Sugar Loaf Mound, the oldest man-made structure in the city and the last remaining native mound. Its exact function is unknown, although similar mounds have been used for burial purposes, as temples, and as viewpoints to send signals to other communities. Built between approximately 800 and 1450, Sugarloaf witnessed settler occupation and was eventually subdivided, partially leveled and built in the early 20th century. In 2009, the Osage Nation – whose ancestors were relocated from St Louis – acquired ownership of part of Sugarloaf, buying and removing a house on its peak to preserve the land and build an interpretive center on a site. adjacent. Two houses remain, however.

Installation view of Anita and Nokosee Fields Way back (2023, ongoing) and Anna Tsouhlarakis’ billboard The native guide project: STL (2023) Chris Bauer. Commissioned by Counterpublic 2023.

In 2021, McAnally and Puleo approached Osage Nation to discuss Sugarloaf Mound’s inclusion in counter public. “Some of that thinking opened up the question: Should something be happening on Sugarloaf itself? That’s a question only Osage Nation can answer,” Puleo says. “Public art occupies the space What forms could be used that would not recreate an occupation of St. Louis?

Puleo invited artists with ancestral ties to the area to respond to Sugarloaf on adjacent land, thereby avoiding occupying the mound itself. “Adding anything to Sugarloaf would be like subjecting it to decoration,” she says. “No singular artistic statement could deal with the complexity of the larger story of Native dispossession and displacement – as well as the erasure of Native presence in Missouri and across the country – better than the mound itself.”

Puleo’s projects include an installation by Osage artist Anita Fields and her son Nokosee which is a series of low platforms similar to those used in Osage ceremonies today. The platforms act as a homecoming and a reminder of what the land could be used for if owned by Osages.

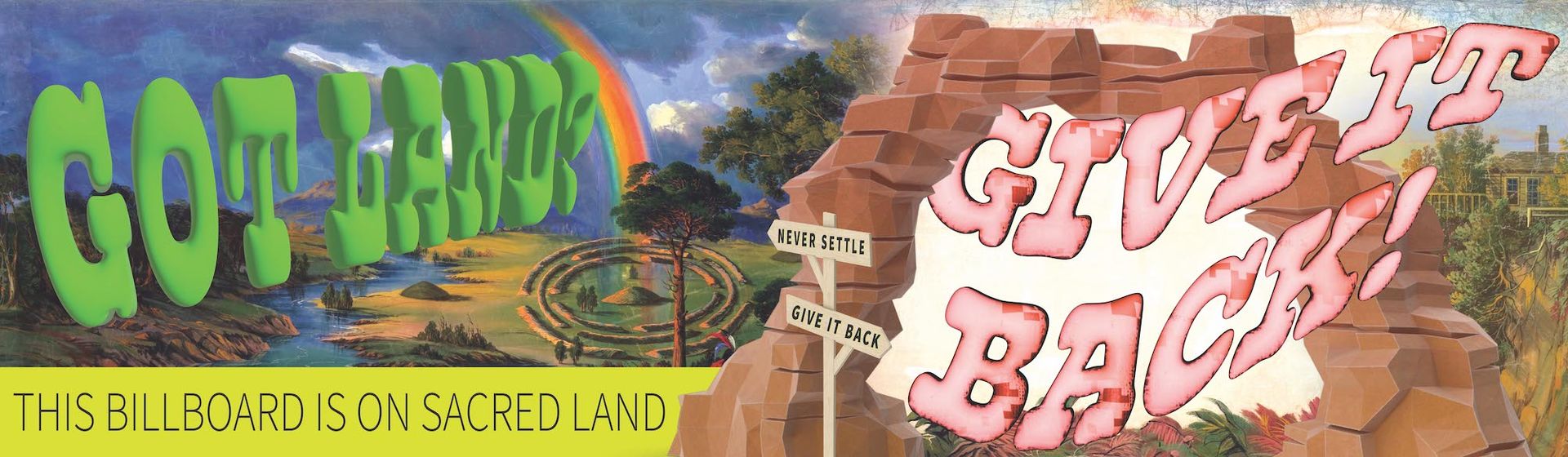

Next to Sugarloaf are also billboards from Anna Tsouhlarakis and New Red Order, both hosted by New Red Order. The Tsouhlarakis billboard reads “WHEN YOU LISTEN TO THE EARTH SPEAK,” prompting visitors to reflect on the ancestral stories of the land’s Indigenous peoples. On the other side, facing the two remaining houses on the site, the New Red Order billboard demands voluntary repatriation.

New Red Order, Give It Back: Stage Theory (2023), billboard at Sugarloaf Mound Commissioned by Counterpublic 2023

While the sites of counter public are primarily public spaces, New Red Order is showing related video at the Saint-Louis Museum of Art. The artwork reflects the larger story of Native displacement, involving the museum building itself, which was originally created for the 1904 World’s Fair and involved the destruction of several Mississippian mounds. The video is a call to action to decolonize and return the land.

“Decolonization, or the return of all land and life to Indigenous peoples, may seem impossible,” says New Red Order. “If it took 400 to 500 years and multiple efforts to dispossess indigenous peoples, how long will it take to reverse these processes? By showcasing, promoting, and being involved in voluntary efforts to return the land, we can encourage others to embark on such efforts as well. To this end, counter publicOrganizers are working to purchase and donate Sugarloaf Mound in its entirety to Osage Nation, including the two occupied homes.

The three-year repatriation plan reflects the larger goal of supporting new futures “as a way to metabolize the violence of the past”, says Vij, who organized projects in the former Mill Creek Valley, an area that was once home to a large black community that was destroyed. as part of an urban renewal initiative. Vij’s projects “focus on redistribution and regeneration, not as a way to offer a narrative of redemption”, but rather to consider the past and offer “material changes and lessons for the future”. , she says.

Jordan Weber, All our releases2022. Spring Church, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St Louis Photograph by Virginie Harold. Courtesy of the Pulitzer Arts Foundation

Included is a regenerative earthwork by Jordan Weber. Serving as a community gathering space and rainwater garden, the earthwork purifies the soil and raises awareness of the importance of stormwater management systems in protecting land and people. Weber’s project reflects the civic orientation of counter publicwhose organizers wanted the presence of the exhibition in the city not to be that of occupation or spectacle, but rather that of tangible and permanent change.

“When art is done well in public, it allows for more dreaming,” McAnally says. “As a long-time resident myself, it’s exciting to see art seep into the everyday experience of the city. One of the best responses we’ve had from St. Louis residents is a desire for more: more public art, more programs and experiences. It is our role to create this space of anticipation and expectation for art on a daily basis.

- Counter-public 2023through July 15, locations across St Louis, Missouri