Coinciding with its ongoing Vermeer retrospective (until June 4), the Rijksmuseum organized a symposium in Amsterdam on March 28 and 29, bringing together scholars from around the world. This offered an unusual opportunity to share the latest developments in Vermeer research. In a field that has been extensively researched over the past 30 years, it is amazing that so much new information has emerged. Last week we revealed the discovery of a probable self-portraithidden under the paint A good sleeper. Here we present some of the most important findings.

Girl with a pearl earring — in 100 billion pixels

Vermeer’s most popular painting, a girl with an earring (c. 1664-67, Mauritshuis, The Hague), has been re-examined using the latest scientific techniques. The results, analyzed by curator Abbie Vandivere and an international team, will be presented to visitors in an inaugural exhibition on June 8, titled Who is this girl?

We can report that state-of-the-art imaging, including 3D digital microscopy, has produced an image made with over 100 billion pixels. Online viewers will be able to zoom in and see huge detail, with even individual pigment particles visible. A four meter high 3D image of the painting will be shown in the foyer of the Mauritshuis.

Computer scientists are also working on a digital visualization of how the painting might have looked when it left the artist’s easel. Behind the maiden, Vermeer originally painted a green curtain, but the blue and yellow pigments have faded, leaving the current greyish-black plain background.

There were also color changes in the shadows on the right side of the girl’s headscarf. These would have originally looked warmer, making the rounded shape of his head more realistic. His face would have been redder, especially in the shadows. Thus, the girl would have appeared more lively and three-dimensional.

As for the pearl, Vandivère describes it as “an illusion – it has no outline – and also no hook to hang it from the girl’s ear: it is just a few brushstrokes of white lead “. We recently reported on our website that a bead of this size would have cost astronomically, assuming the maiden might well be depicted with a glass ball.

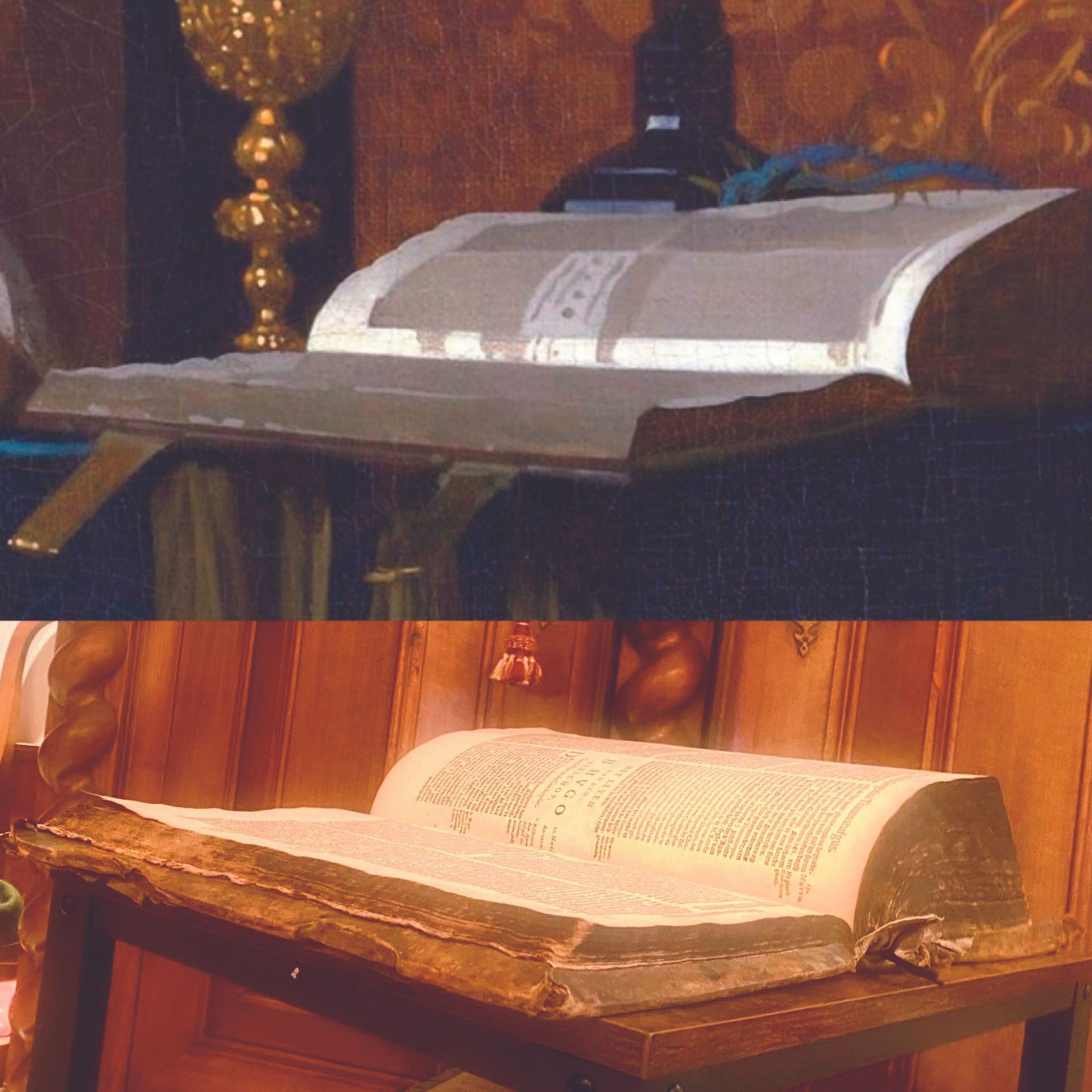

From top to bottom: Detail of Allegory of the Catholic Faith (circa 1670-74) / A photo from the 1640 edition of Legend of Heylighen (legends of the saints) by Pedro Ribadineira and Heribert Rosweyde

Metropolitan Museum of Art / —-

A page of a book identified

Evelyne Verheggen, a researcher at the University of Antwerp, has identified the open book that appears in Vermeer’s work Allegory of the Catholic Faith (c. 1670-74, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, below). This is the 1640 edition of Legend of Heylighen (legends of the saints) by Pedro Ribadineira and Heribert Rosweyde (left, top: a detail of the painting; left, bottom: a photo from the book).

She was also able to identify the page to which he is opened in the painting, p.546, which includes the text on Hugo of Lincoln, who died in 1200. Hugo is venerated on November 17, the date on which the French Army was forced to withdraw from Utrecht in 1673. If there is indeed a connection to the Hugo page, as Verheggen suspects, then the painting’s dating should arguably be reduced from 1670-74 to late 1673 or 1674. Verheggen thinks that the subject of Vermeer’s painting is not “faith” (as evidenced by its traditional title), but more specifically Mary Magdalene. She sees the figure of the woman as representing the Magdalen, “a personification of devout, praying Catholic women”.

by Vermeer Allegory of the Catholic Faith (circa 1670-74)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Patron of Vermeer

In February The arts journal revealed that Vermeer’s main patron was a woman: Maria van Ruijven, rather than her husband Pieter. We can now report further evidence, presented at the symposium by Judith Noorman, art historian at the University of Amsterdam.

The document is a 1664 codicil to Maria’s will. We already knew that a year later she had bequeathed 500 florins to Vermeer. But the newly discovered record shows that the bequest was older.

The codicil, discovered in the Leiden archives, is important for another reason: Maria gave a painting “of her choice” to a friend, Nicolaes van Assendelft. Maria and Nicolaes seem to have shared a mutual love of art.

Noorman, who studies the impact of women on the Dutch art market, told the symposium: “The reason why Maria has been neglected and why Pieter has received the most attention is because as than a man, he was easier to place and to understand in a world of men.

A new Vermeer document

A Dutch scholar, Rozemarijn Landsman (of Columbia University in New York), has just discovered a previously unknown archival document bearing Vermeer’s signature. This is the bequest of a piece of land to the artist’s wife Catharina Bolnes. Full details will be published in Landsman’s next article in the Art History Journal. Oud Holland. At Vermeer, every archival reference matters.

The Philadelphia version of Lady playing the guitar.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Does Philadelphia Guitarist a 38th Vermeer?

Arie Wallert, a former scientist at the Rijksmuseum, told the symposium about his research on another version of The guitar player (the universally accepted version, from around 1670-72, is in Kenwood, London). The other version (above) is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it has languished in store since its decommissioning in 1927.

As The arts journal reported on his website in April, Wallert believes his technical examination suggests the Philadelphia painting is not just a 17th-century work, but is actually “a Vermeer painting.” The two compositions are virtually the same, except for one key difference, the hairstyle of the guitarist.

Sasha Suda, Director of the Philadelphia Museum, comments: “The future of our lady with guitar will be to inspire discussion, embrace scholarship, and seek further knowledge and enlightenment from this mysterious painting nearly 350 years after its creation.”