“Hip-hop is a canon. He’s only 50 years old and he belongs in museums,” Asma Naeem, director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, told Artnet News. “It’s not just about temporary exhibitions; it belongs to the permanent collections of museums.

On the occasion of 50 years of a genre born in the Bronx during a birthday party hosted by DJ Kool Herc, the institution presents its first exhibition on the theme of hip-hop, entitled “Culture: hip-hop and contemporary art in the 21st centuryto consider how form has shaped all sorts of cultural productions. The show, which opens today, isn’t the only one to commemorate the movement’s 50th anniversary—Photography And the Museum at the FIT also do, but it is the one that weaves the global culture with works of art in a collage of consequent objects and images.

Installation view of “Culture: Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century” at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo: Mitro Hood/BMA.

One of the objectives of the exhibition, set by Naeem and his team of curators, including Gamynne Guillote, is to dismantle the divide between hip-hop and high art. As Guillote said in his opening statement before a preview visit to the gallery: “The separation between the street and the gallery is a mistake”, with perhaps an unintended rhyme reminiscent of the pun of Biggie Smalls, the rapper who inspired a piece by Mark Bradford draped behind his.

Title Biggie Biggie Biggie (2002), Bradford’s work of gauze “guard papers” used to curl hair, forms an abstract representation of the Brooklyn MC in the first part of the exhibition. Within this same room, described by Guillote as a “tasting menu” of the sections to come, there is also the bright pink double portrait of Zéh Palito transplanted from Baltimore, It was only a dream (2022), a Basquiat canvas from 1983 dedicated to jazz musician Charlie Parker and a Dapper Dan down jacket from 2018.

Zeh Palito, It was only a dream (2022). Photo courtesy of the artist, Simoes de Assis and Luce Gallery.

This collage of styles offers a positive response to a textual work by New York-based artist Shirt, installed in the next section of the language-focused exhibit, which reads in bold black letters: “CAN A RAP SONG HAVE THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ART. “It’s a statement, less a question, that confirms the exhibit’s thesis, but also underscores the timeless message that runs through hip-hop.

Through its elements, hip-hop has always been a way for black artists in particular to express the grind of systemic oppression, with rap and fashion offering ambitious counterpoints to reclaim painful narratives and history. The Ornament section of the exhibition offers such a juxtaposition of trauma and beauty.

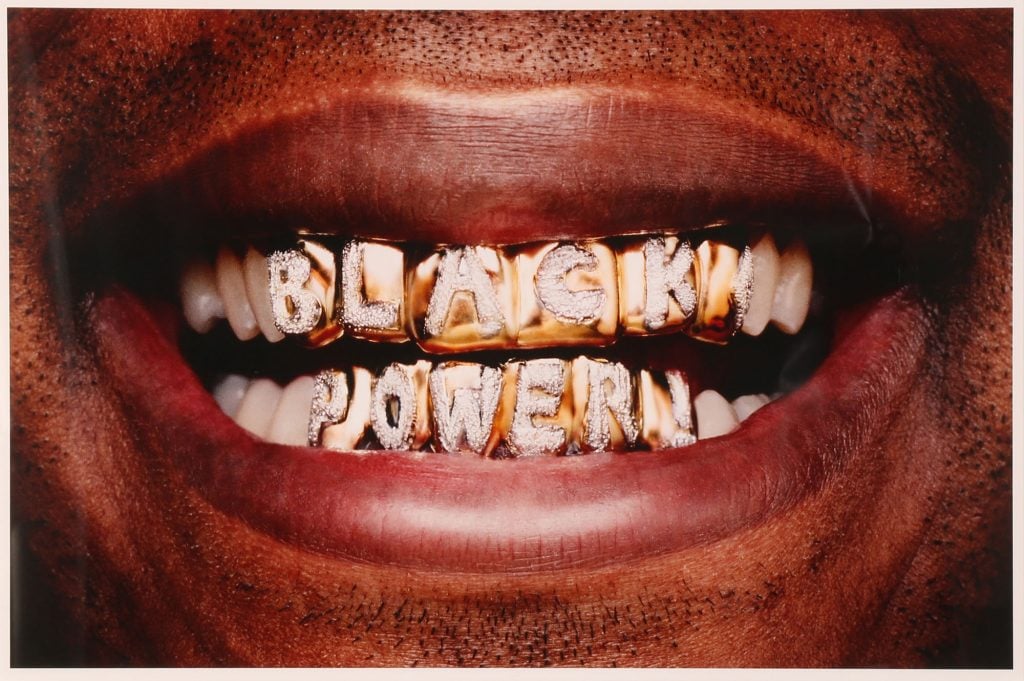

Hank WillisThomas, Black Power (2006). Photo courtesy of Barrett Barrera Projects.

We see Robert Pruitt’s arrangement of gold chains reflecting transatlantic slave trade passages, that of Hank Willis Thomas Black Power (2006) gold grids, and Deanna Lawson’s portrait of two men with bold African facial jewelry next to a snapshot of George Washington’s rotting dentures. Naeem described these modes as an “understandable language” for translating hip-hop’s cultural messages to a wide audience.

Baltimore sculptor Murjoni Merriweather and her hair braid sculpture ZELLA (2022) are also included to center a more personal perspective. “The section is very much about adornment and I feel like it speaks to the goals of my piece, but also to myself, as a person,” the artist explained. “With hair, we use it in a way to adorn ourselves, to make us proud.”

Murjoni Merriweather, ZELLA (2022). Photo courtesy of the artist, © Murjoni Merriweather.

Hip-hop fashion also had tremendous commercial appeal, as shown in the Brand section of the exhibition. The gallery opens on a graffiti panel, contrasting it directly with a case Travis Scott Air Jordan 1 and a Cross Colors denim bucket hat, highlighting how a criminal act of vandalism has, over the decades, contributed to the birth of a commodity culture.

There’s even a display of Pharrell Williams’ now-legendary Buffalo Hat (which made its Grammys debut in 2014), which was originally designed by Vivienne Westwood and inspired by Malcolm McLaren’s 1983. duck rock album. Curators had to borrow the hat from fast-food brand Arby’s, which recently bought the hat at auction.

Installation view of “Culture: Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century” at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo: Mitro Hood/BMA.

“It’s always been multi-disciplinary and it’s always been about restlessness,” said Guillotine on hip-hop. “He therefore finds a very natural allegiance to the idea of commerce.

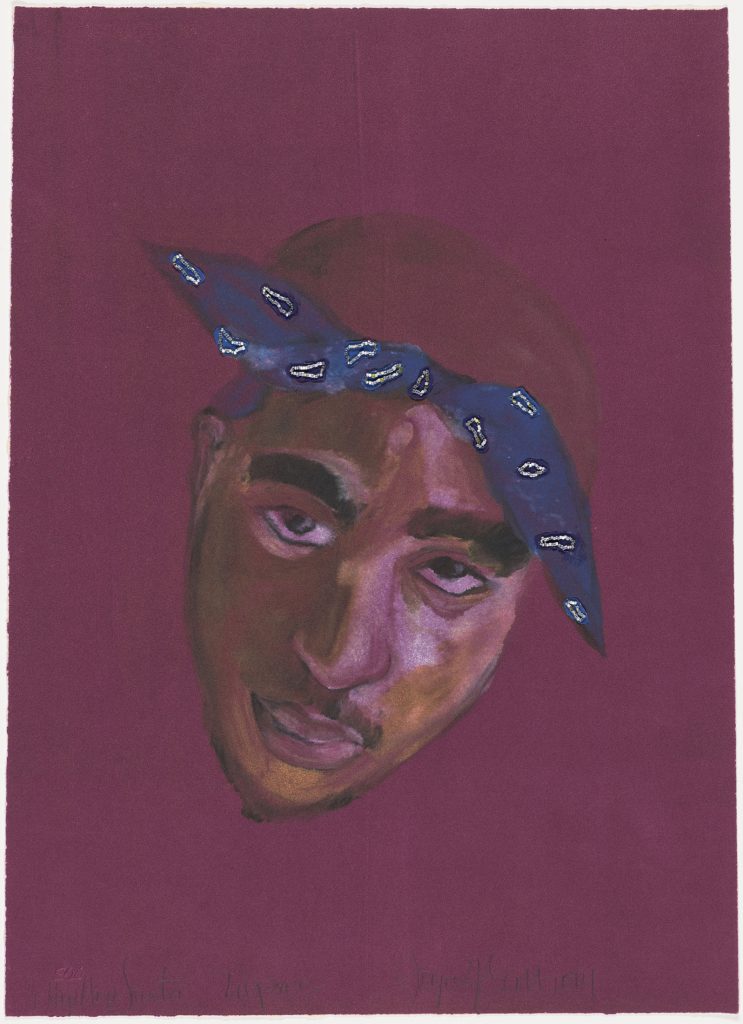

Naeem’s favorite section, Tribute, adds to this cross-generational conversation with a tribute to Tupac Shakur, who elevated gangsta rap into a true art form. The most moving of the three pieces dedicated to the late rapper here is Alvaro Barrington’s aluminum and cardboard burlap spelling out Shakur’s powerful words, “They’ve got money for war but can’t feed the poor,” in thread.

Joyce J. Scott, Saint of hip-hop, Tupac (2014). Photo: © Joyce J. Scott and Goya Contemporary Gallery.

“Hip-hop is youth. But how this gap between youth and respect for previous generations constantly jumps and collides, it all happens in this section,” said Naeem, who added that Tribute remains his favorite gallery in the exhibition. “I love Tupac.

“The Culture” concludes with two rooms, themed Ascension and Pose, each containing pieces exploring hip hop’s complex relationship with grief and the afterlife (gender, sadly, keep seeing a lot early death). Here, the white-on-white silk print of John Edmonds and the dazzling portrait of Ernest Shaw Jr. of Baltimore, I had a dream where I could buy my way to heaven (2022), summarize both the gains and losses of hip-hop culture.

Installation view of “Culture: Hip-Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century” at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo: Mitro Hood/BMA.

The exhibition itself is extended, intentionally, in the contemporary art wing of the BMA. In the middle of this crossover hangs Devan Shimoyama’s sculpture, made of Timberland boots, rhinestones, silk flowers, epoxy resin and coated wire. A highlight of the show. This mix of street accessories and gallery fabrics evokes a beauty that encompasses the streets. “Hip-hop conveys different kinds of beauty, other forms of beauty that go along with the Western canon,” Naeem said.

“These worlds have always been in dialogue,” Guillote added of the coexistence of hip-hop, fashion and art. “It’s extremely important because there’s power in it. It helps someone to assume that there is this thing we call ‘the street’ and there is this thing we call ‘the gallery’. How scary would it be if there weren’t?

“Culture: hip-hop and contemporary art in the 21st centuryis on display at the Baltimore Museum of Art, 10 Art Museum Drive, Baltimore, through July 16.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.