Museum regulars are pretty By the way with accepted rules: keep your distance from exhibits, don’t touch anything and try to be quiet. So what happens when an eccentric museum director expressly encourages you to break them? That’s the odd proposition put forward by the Sainsbury Center near Norfolk, England, when it relaunched this weekend.

Under the new program, museum visitors are invited to interact with the works of art in unprecedented ways, including hugging a Henry Moore or whispering secrets to a Giacometti.

“We are the first museum to understand art as a living entity,” center director Jago Cooper told Artnet News. “Great artists are people who have the ability to channel the uniqueness of the human soul into clay or onto a canvas, and materialize some aspect of their anima. At that point, art captures the life force of the individual.

The concept of “living art” is a passion project of Cooper, and the freedom to realize it was the main condition of his slightly surprising decision to leave a comfortable senior role as head of the Americas at the British Museum and join this center relatively provincial. in 2021. The idea seems exciting, but how do these encounters with “living art” translate in practice? Artnet News decided to give the tour a try.

The first step was a battle with rural phone service providers to download Smartify, a free app offering curated information about museum exhibits much like an audio guide. The first tour, “Living Art”, started with Henry Moore mother and child (1932). Cooper’s voice in my ear instructed me to kiss the statue, make eye contact with the mother, then close my eyes and try to conjure up my first memory of being detained as a child .

As that memory slipped away, I was encouraged to gently stroke the groove that ran along the back of the sculpture, which was pleasantly smooth and cool to the touch. This sensuous moment has been compared to Moore rubbing oil on his mother’s back as a child, which he has often described as his first sculptural experience.

The author hugging Henry Moore, mother and child at the Sainsbury Center in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

“That feeling in you, that feeling of protection, that’s what Henry was trying to create with this work,” Cooper told me. “Open your eyes and look again at this sculpture, and understand that art is not a set of rules to read, it’s an emotional state of mind to enter.”

I wondered if my actions might damage the sculpture, but Cooper explained that there was video footage of Moore himself telling one of the center’s founders that anyone who thinks they can understand his art without touching it doesn’t know nothing to sculpture. Cooper conceded that the work is likely to acquire a patina over time, adding “but for me it’s part of the aging process. I’m not trying to preserve it in pristine condition.

“Of course, everything has to be done very carefully, on a case-by-case basis,” he said. “A lot of artwork isn’t meant to be touched, but for some things we think we have clear evidence that they want to be touched.”

The Author Moving with Three Dancing Female Figures (c. 618-906) at the Sainsbury Center in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Next, there were three dance figures from the Tang Dynasty. “These are not static ceramic vessels in a case, they are living embodiments of movement and dance that have taken place for over 1,200 years in China,” Cooper said.

As evocative sounds filled my ears, I was encouraged to raise my hands and sway like no one was watching, though I couldn’t help stealing a few sideways glances to make sure no one, in fact, did.

“It may seem odd to move around the gallery like this, but it might free you from the restrictive ways you’ve been told to engage in art,” Cooper promised. “By letting go of conventions, you can open up and connect with art in a much more creative way.”

The author gets close enough to see Francis Bacon’s hair Study for a Portrait of PL, no. 2 (1957) at the Sainsbury Center in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

I snuck into Francis Bacon Study for a Portrait of PL, no. 2 (1957), depicting her violently abusive partner Peter Lacy. In catchy tones, Cooper set the mood: “His studio was a place of alcoholic haze, cigarettes rubbing against canvas, trauma, restlessness and angst. You can literally feel the energy in him transfer to the canvas.

As the audio prompted, I leaned unusually close to the canvas to spot one of Bacon’s hairs on Lacy’s shoulder. It’s the kind of detail that reminds us of the immediacy of artistic creation and that these works are the remnants of real lives lived.

Another interesting aspect of the museum’s relaunch was a second audio tour featuring new ways to educate museum visitors about the works instead of interpretive wall texts. Listeners can choose to hear from a creator, an academic expert, or someone with lived experience. In the case of a pair of snow goggles, for example, we can hear contemporary artist Tarralik Duffy’s perspective on the bone carving process, or Greenlandic hunter Aleqatsiaq Peary on how glasses are used.

This visit, Cooper said, “is an attempt to say that the museum is not an authority by which the knowledge is given to you to understand the art. They are living entities and there is no right or wrong way to encounter them.

The author seen through art from inside a shop window at the Sainsbury Center in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

A third tour offered even more experiential encounters with art. “A lot of people who go to galleries and museums don’t like to read a lot of texts, how do you introduce them to living art?” was the problem that Cooper kept coming back to.

Visitors are invited to write a museum label themselves and step into a display case. Their audience? A host of intrigued artwork all looking back.

The gimmick looks fun for a few moments, but what does it hope to accomplish? “It’s weird, because when you walk in there, you can’t help but activate your mind that these works of art live and watch you,” Cooper explained. “You become objectified and that reverses the agency of the relationship with art.”

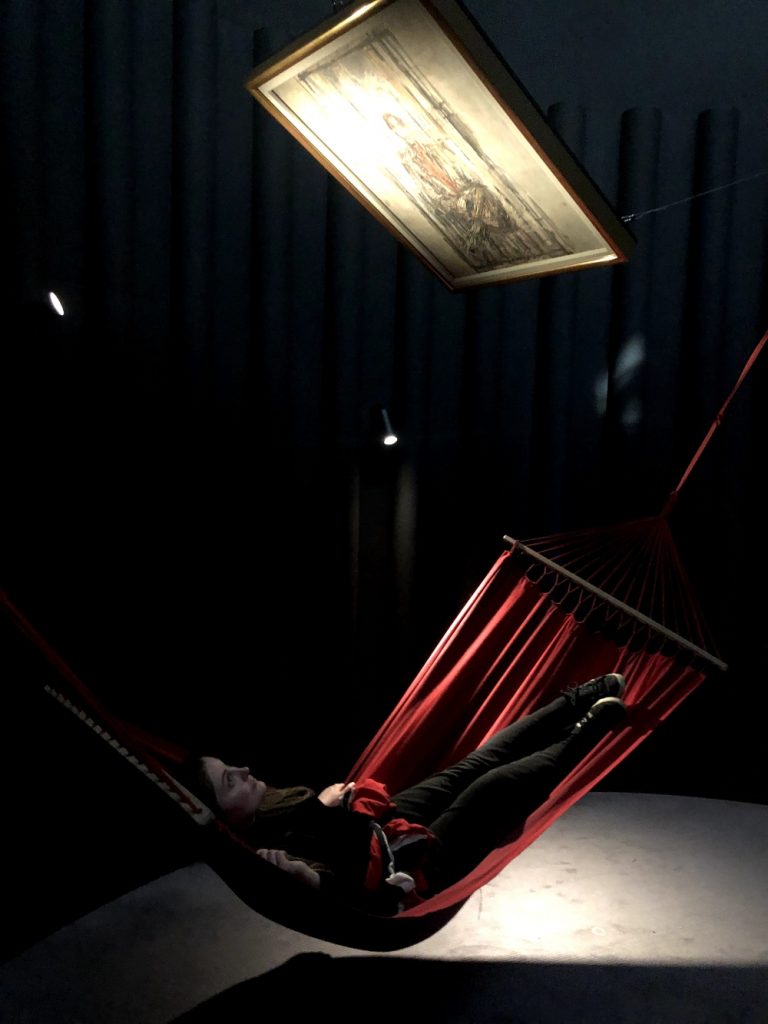

The author lying in a hammock and sharing secrets with a portrait of Giacometti at the Sainsbury Center in Norfolk, England. Photo: Jo Lawson-Tancred.

Duly humiliated, I snuck into a circular structure known as the silo, a dark, sequestered nook where a hammock swayed beneath a 1948 portrait by Giacometti of his brother Diego. I couldn’t see any text identifying the painting but, instead of a formal introduction, I spotted an ominous sign urging me to “tell her a secret you’d never tell a human.”

“Some people will say that art isn’t alive because it doesn’t speak. It’s not true, there’s a two-way communication,” explained Cooper, who hopes his new methods will help us all deepen the relationships we already form with our favorite works of art.

Founded by famous British supermarkets Robert and Lisa Sainsbury to manage their hoard of over 300 objects, the museum has always looked for other ways to engage visitors with art. In 2022, visitor numbers have risen to around 105,000, an improvement from the pre-pandemic average of 95,000, but it’s clear Cooper is keen to do all he can to boost attendance.

To that end, a series of provocative new temporary exhibitions are already in the works and promise to answer life’s biggest questions. First of all, this fall, it’s “how do we adapt to a changing world? Over time, visitors can expect to ask “what is truth?”, “why do humans still kill each other?” and “what is the meaning of life?” It’s clear that Cooper is keen to keep surprising his audience, it remains to be seen how well they will react.

More trending stories:

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.