Mina Loy (1882-1966) was an innovative modernist poet and writer of the interwar period. Although she was trained as an artist, her art is much less known, a condition linked to her fragility and her difficulties in surviving in the face of adversity. She was born in London to a Hungarian-Jewish father and an English Evangelical Christian mother; two of Loy’s four children died in infancy and, having divorced her first husband, the English painter Stephen Haweis, she literally lost her second, the provocateur Arthur Cravan (pen name of Fabian Lloyd) when he went to sea never to return.

She had met Cravan in 1917 in Dada circles in wartime New York, where she contributed poetry and prose to avant-garde magazines. In the Paris of the 1920s, when she published her first collection of poems, The Lunar Baedecker (1923, the ‘c’ apparently a typesetter’s insertion), Loy established a successful business producing lampshades of intricate artistic construction. By contrast, back in New York in the 1940s, she made works so provocatively precarious that they were uncommercial, indeed anti-commercial. Berenice Abbott, Joseph Cornell, Marcel Duchamp and Peggy Guggenheim were among the small group that admired Loy’s works, but the main challenge today is that very little remains from four decades of production.

This publication accompanies an exhibition curated by Jennifer R. Gross for the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Maine (through September 17), which faces the task of making sense of the fragmentary remains of Loy’s art. It is the first volume to address in detail his artistic production, from his initial training at the Kunstlerien Verein in Munich in 1900 then at the Académie Colarossi in Paris until his late “assemblages”. Gross’ introductory chapter takes up more than half of the publication and is followed by a shorter chapter.

excerpts from poet Ann Lauterbach, art historian Dawn Ades and author/editor (and renowned Loyalist) Roger Conover. All contributions are accompanied by images of Loy and his entourage, as well as photographs of lost works, articles and archival documents.

Loy presents formidable exhibition and publication challenges

Loy’s reputation as a writer (poet, satirist, polemicist, critic, feminist) and the international scholarship that surrounds her underpin the way the visual works here are brought to public attention. Contributors approach the task discursively: Lauterbach considering Loy’s engagement with truth and beauty, Ades exploring the trajectory from Dada to late constructions, and Conover writing more self-reflectively following his 50-year experience of study and edition of Loy’s work. It’s a noble undertaking but, as Conover says, “Mina Loy presents formidable challenges to exhibition and publication. Foremost among these, as noted, is the debilitating loss of material, although this publication may cause some “lost” works to be recognized from period photographs and reappear. As it stands, the material that remains is sometimes dangerously thin. Loy’s involvement with the Futurists in Florence, for example, encouraged Gross’s suggestion that she made paintings “to test her hand on their fragmented and forceful style of painting”, but this description is

undermined by a footnote declaring the works “now lost”. It is of course not the fault of the curator if the works are missing, but the publication’s device of directing readers to an image of a document (as in this case), rather than a work, is turns out to be disappointing.

Contrasting readings

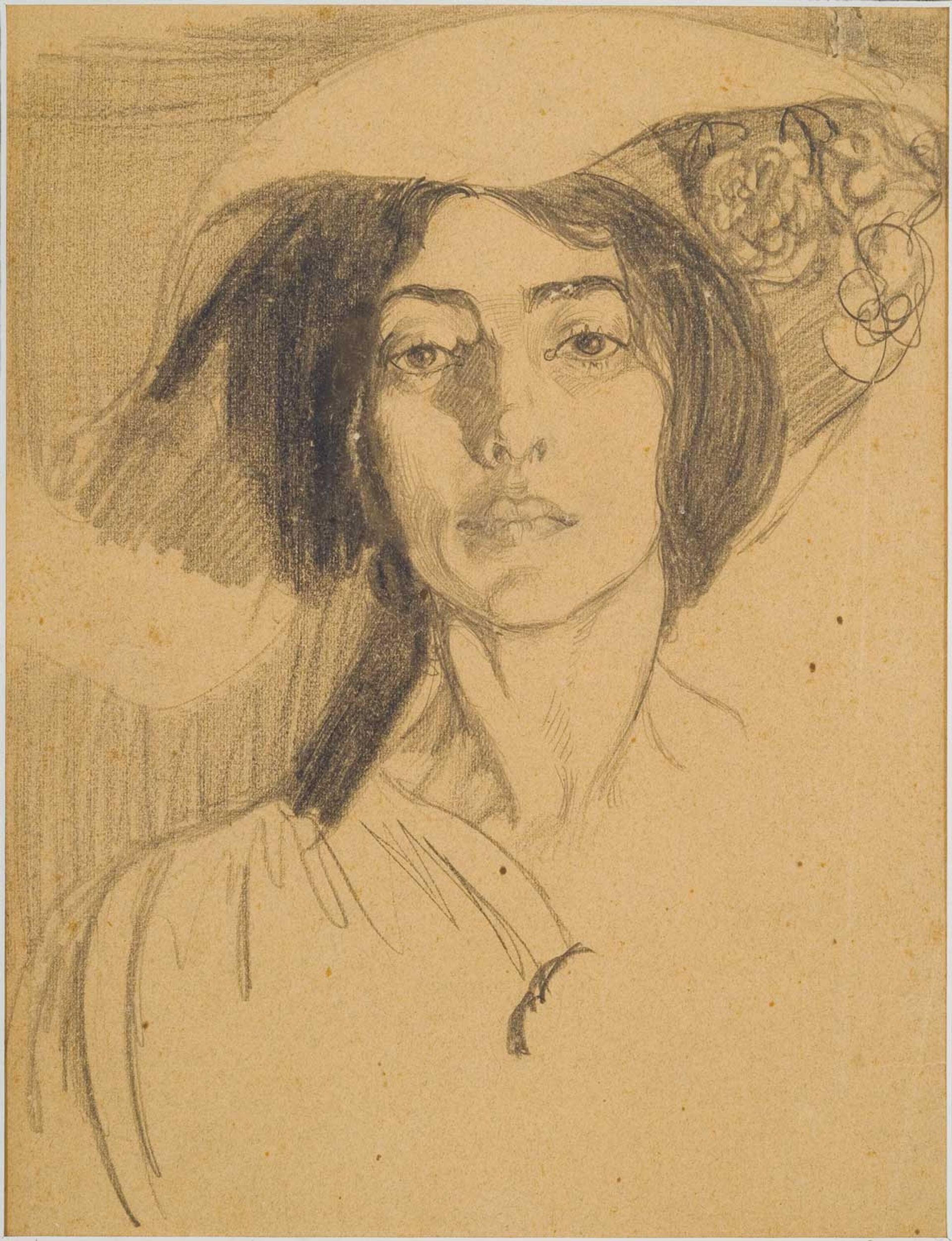

Among the earliest surviving works is a self-portrait drawing from 1905, In front of the mirror. Its power is enhanced by the fact that three of the contributors interpret it in markedly different ways. Writing “a blank, dull stare, a gloomy self-esteem,” Gross tellingly associates the drawing with Loy’s grief at the death of her first child. Ades sees the design as “rather imperious…in all Edwardian splendor with a magnificent hat”, while for Lauterbach it is sensual: “his eyes…look back with a coldly detached expression of appreciation”. All three views are true, so it can be argued that only a design of considerable power can elicit such a variety of responses.

Loy’s self-portrait, In front of the mirror (circa 1905), invites multiple interpretations in the book

Photo: Jay York

The most numerous survivors are the monochrome blue paintings that Loy exhibited at the New York gallery of her son-in-law, Julien Levy, in 1933 (a gallery for which she was the successful Parisian agent). The paintings, for which Levy coined the term blueness (playing on greyness), are ethereal in their cosmic subject matter of idealized heads. They combine Loy’s experience of the Parisian avant-garde and her beliefs in Christian Science, and are performed in a surreal illusionist technique comparable to that of her friend and protagonist in her 1937 novel. Insel—the German painter Richard Oelze. In a striking sentence, Loy’s alter-ego narrator imagined “drawing[ing] nascent form” of chaos so that “the female brain can perform an act of creation”. This vision of a feminine Genesis is powerfully anti-patriarchal and exemplary of Loy’s feminism. (This quote, however, is used – in full – three times; one of many signs of rushed editing. Additionally, Untitled (surreal scene) is included among the opening images, though Gross suggests it could be Loy’s daughter Fabienne; and the numbering of the illustrations is confused with fig. 3.13 and following.)

Loy’s assemblages of the late 1940s and early 1950s are extraordinarily, even strangely, individual. Thanks to the support of Abbott, Duchamp and Levy, they were shown by David Mann at the Bodley Gallery in 1959, their old-fashioned realism arousing general indifference. They address, sympathetically, the condition of society’s most neglected members – the drunken “bums” of New York’s Bowery neighborhood – and their wealthy associations are widely discussed in this publication. The haggard face of Christ on a clothesline seems to evoke the flophouses of the Bowery where, as Simone de Beauvoir noted in 1947, tramps “sleep sitting on benches, their arms leaning on a rope…until the end of their time; then someone pulls on the rope, they fall forward, and the shock wakes them up”. Loy took these assemblages to a substantial scale, their fragility echoing that of the lives of his subjects. Ades questions the idea that Loy uses junk food, noting how his neat work was consistent with his “habit of making treasures out of undervalued things”. These materials are however vulnerable and it should be noted that a number in Shared cot– a bird’s eye view with nine sleeping “tramps” – changed position: in 1959 it was standing (as recorded in Abbott’s photograph) where it is now buckled and lined up with most of its companions. Here as elsewhere, there is still much to explore.

What the curator – and we as an audience – have been faced with, therefore, is remarkable promise but enticing fragmentation. With the exception of The hunting house, which Guggenheim acquired in 1959 (and whose absence from the exhibition suggests the kind of behind-the-scenes struggles that haunt all projects), this seems like as complete a gathering as one can get with such a weathered body of work. As Loy herself wrote: “The public and the artist can meet at any point, except – for the artist – that which is vital, that of pure uneducated vision. The ambition to make such an engagement possible, even given the limitations of surviving material, ensures the necessity of the current project.

• Jennifer R. Gross (ed) with contributions from Jennifer R. Gross, Ann Lauterbach, Dawn Ades and Roger L. Conover, Mina Loy: Strangeness is inevitablePrinceton University Press, 232 pages, £42 (hb)

• Matthew Gale is an independent artist and curator