Munstead Wood, Surrey’s famous Arts and Crafts house and garden, has been acquired by the National Trust, the charity for the preservation of historic houses, gardens and landscapes, with financial assistance from the UK Government, ‘for the everyone’s pleasure”.

House and Garden, a globally significant integrated Gesamtkunstwerk where house and garden are subtly but inextricably linked, was created by architect Edwin Lutyens for and with his client and mentor Gertrude Jekyll. It had been put up for sale, at an asking price of £5.25million following the March 2022 death of its owner Marjorie Clark. Clark and her husband Robert Clark, a prominent City of London banker who died in 2013, renovated the house and garden for half a century after acquiring the place in the mid-1960s. They had for many years made the garden available to groups of visitors. It was, said Robert Clark, “the best investment I have ever made”.

The National Trust said it had acquired the house through a private sale and had “begun raising funds to support the restoration and reimagining of the garden and the house”. The trust said it was “working with the local community and partners to develop plans on how best to open the property to visitors in the future”.

The particular quality of Munstead Wood lies in the close and graduated integration between the wood, the wooded garden, the herbaceous borders, the paving and, all at the same level, the ground floor of the house which is built in materials premises, Surrey Brick and Bargate. stone, and placed in its wooded setting as if to be discovered by chance rather than by design. The sense of discovery continues in the ground plan of the house, full of unexpected turns and views. Everything is a gradual revelation, and the aesthetic inside and out is enhanced by Lutyens’ early artistic mastery of falling light on masonry, smooth carving and deep windows.

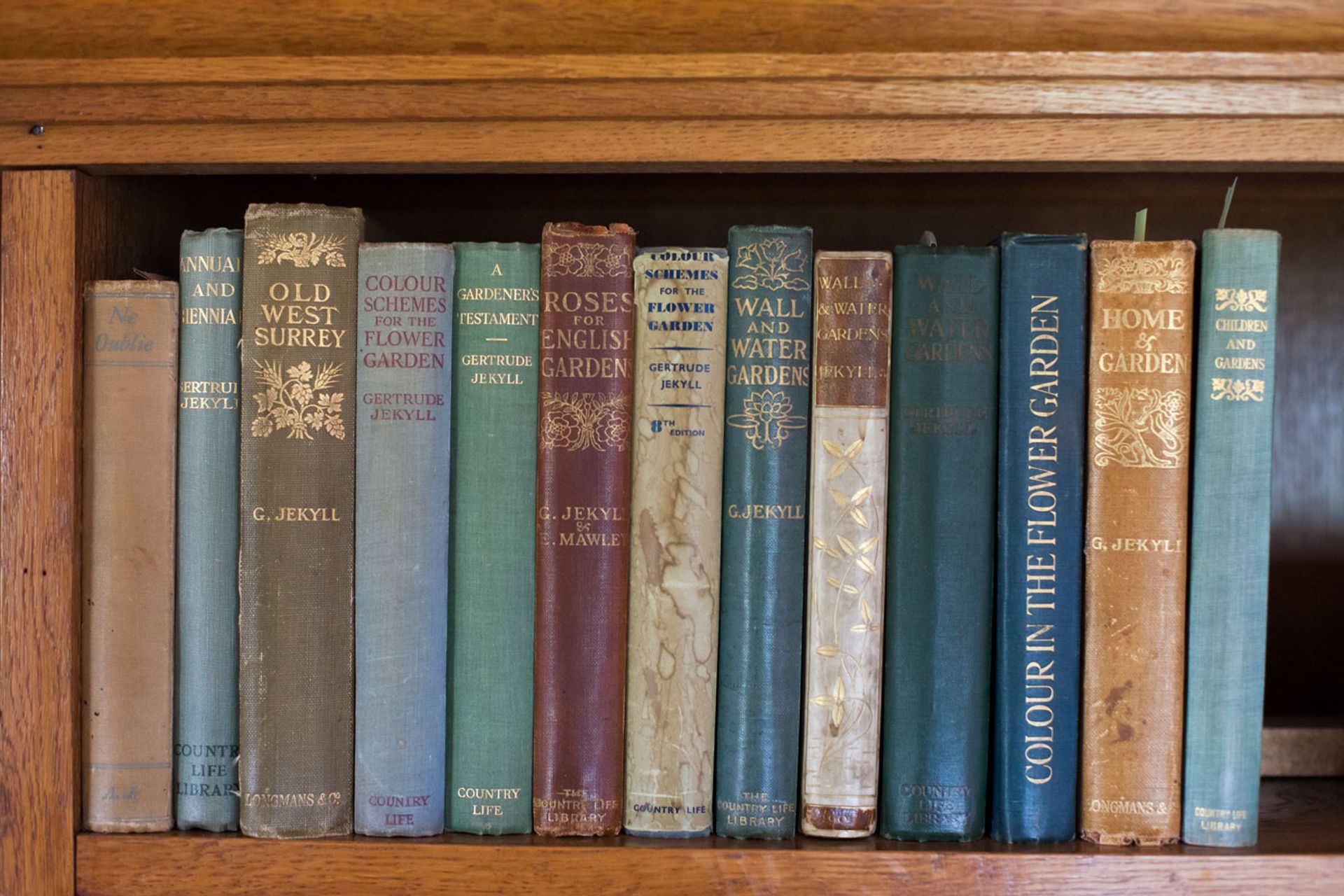

Books by Gertrude Jekyll at Munstead Wood. Her work as a writer, journalist, seed seller, florist and landscaper helped finance the upkeep of the house and garden. Megan Taylor/National Trust Pictures

The house was completed in 1896 to plans by 27-year-old Lutyens for his mentor Jekyll, a formidable writer, artist, historian of crafts and country life, horticulturist and garden designer. By 1886 she had acquired her site, 13 acres of unpromising Surrey moorland, and planted a woodland in which she developed her own form of informal gardening and placed a series of practical buildings for writing – she was a serial contributor To country life magazine and book producer on gardening, crafts and buildings – and the sale of seeds and flowers. Munstead Wood has always been a place of work for Jekyll, further funded by his writing and journalism.

In 1889 she met Lutyens, then prodigiously talented, all 19 years old, with a lingering memory for the architectural details of local building in Surrey, where he had spent his childhood summers. It was an encounter that made him an architect. Jekyll’s austere, almost monastic aesthetic and his sense of “correctness” informed his work as a constructor of romantic and vernacular buildings, but also, later, as a master of classicism responsible for masterpieces. work, including Drogo Castle in Devon. , the great war graves spread across the killing fields of Flanders and Normandy, the imperial capital of New Delhi and his great unfinished project for the Catholic Cathedral of Liverpool. Lutyens in turn offered Jekyll a whole new avenue of work as a garden designer to a fashionable clientele (work which helped pay for the upkeep of the house and garden), usually in cahoots with Lutyens in the country house cabinet he built in the late 1890s. and 1900s through their collaboration at Munstead Wood.

Photograph of William Nicholson’s portrait of Gertrude Jekyll Courtesy of the National Trust

Jekyll herself was a pivotal figure in the history of the Arts and Crafts movement. A talented amateur artist, she had attended lectures by John Ruskin – the movement’s intellectual founder – and William Morris, the master of applying the movement’s principles in decorating and interior design. When she once suggested that Ruskin build a house in Surrey decorated with marble, he insisted that she consider whitewash and tapestry as her aesthetic instead. It was a life-changing moment that went on to influence the aesthetic of Munstead Wood itself, but also a series of masterpieces on which Lutyens and Jekyll collaborated, including the restoration of Lindisfarne Castle (1906 ) and Lambay Castle, Co Dublin (1908-10) and a new home, Deanery Garden, for Edward Hudson, proprietor of Country Life magazine, a crucial figure in promoting the work of Lutyens and Jekyll.

The sophisticated sense of geometry and play with a segment of a circle, which Lutyens developed at Munstead Wood, both in the planning and elevation of the arcades and lintels, was nurtured by 50 years of subsequent work. The arc is fundamental to his most sophisticated, almost abstract designs: the Cenotaph in Whitehall, whose seemingly straight elevations meet at the junction of their arched sides miles above the ground, and the stepped arches of the Thiepval war memorial and, on an even more massive scale, in the great unbuilt aisles of Liverpool Cathedral.

Another notable work by Lutyens in Surrey, Goddards, is maintained by the Landmark Trust, the charity which restores small historic buildings and lets them out to its members as holiday accommodation, and is the headquarters of the Lutyens Trust, the charitable organization dedicated to research and education on the work of the architect.

Munstead Wood and its owner had strong ties to artists of the day. Jekyll had photographed local houses with her friend Helen Allingham, who left behind distinctive watercolors of Munstead Wood, including the famous summer herbaceous border, 200 feet long and 14 feet deep. William Nicholson left two indelible portraits of Jekyll. A powerful portrait from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery – left to the gallery in 1947 at the express request of Lutyens, who died in 1944 – and a delightful portrait of his gardening boots painted, legend has it, because Nicholson was struggling to make every enterprising and creative Jekyll stay still enough to capture their likeness.

When Robert and Marjorie Clark bought Munstead Wood in the 1960s, 30 years after Jekyll’s death, many of its borders and rockeries had been grassed over as a saving. Many of the finest trees in the wood were destroyed in the great storm of October 1987, after which the Clarks’ head gardener suggested removing the grassed areas and restoring Jekyll’s full design, both near of the house and in the surrounding woods. A project that was triumphantly carried out and continued by Annabel Watts, the leading expert on the history of home and garden, who was head gardener at Munstead Wood for 19 years.