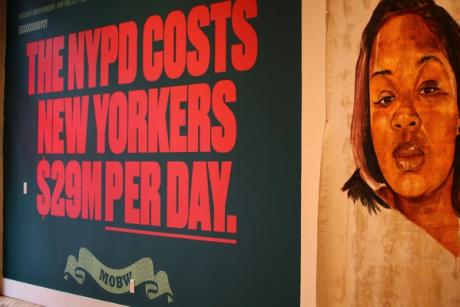

A low-key storefront in Manhattan’s popular Nolita neighborhood now houses the Museum of broken windowsan ephemeral space whose main exhibition asks the following question: how else could New Yorkers spend the 29 million dollars a day that the municipal government devotes to the New York Police Department (NYPD)?

The show, 29 million dreams (until May 6), turns the figure into a conceptual opportunity, showcasing community resilience while highlighting the human cost of over-policing in New York City, which has the largest police force in the nation. The race of the exhibition coincides with that of New York City Mayor Eric Adams adoption of the latest city budgetsupposed to maintain the NYPD funding at $11 billion while cutting social service budgets that were already underfunded.

“Eleven billion is not a number that makes sense to anyone who isn’t a billionaire,” says Johanna Miller, director of the Education Policy Center at the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU). “But we can understand $29 million a day. With what the police are spending just to cover their overtime this year, we could have kept the city libraries open six days a week.”

The Museum of Broken Windows is a collaboration between NYCLU and Soze, a creative strategy agency. It is inaugural exhibition in 2018 featured 60 works critical of the NYPD”stop and search” practice, which was criticized after data showed that 90% of those detained were black or Latina. This iteration takes its name from the “Broken glass” theory, coined in 1982 by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, which argues that visible signs of “antisocial behavior” create environments that encourage crime. The theory heavily influenced New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s approach to law enforcement in the 1990s.

29 million dreams traces the legacy of the “broken windows” strategy in the killings of black and brown civilians by police across the country, an epidemic that inspired global protests for racial justice in the summer of 2020. Despite a welcome wave from abolitionist sentiment at the height of Covid -19 lockdowns, the Adams administration relied heavily on the NYPD to deal with all sorts of ills.

“We cannot ask or expect the NYPD to be the answer to everything from lack of affordable housing, to severe mental health care shortages, to school discipline,” says Donna Lieberman, executive director of NYCLU. “As mayor and [city] the council negotiates the city budget, they should break away from police problem solving, visit the broken windows museum and make our dreams come true.

The exhibition is co-curated by Daveen Trentman of the Soze agency and Terrick Gutierrez, an interdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles. It highlights a wide range of works by more than 20 artists, many of whom have experienced first-hand the consequences of excessive police surveillance.

Artist Russell Craig, whose portrait of Louisville police victim Breonna Taylor hangs solemnly on the first floor of the exhibit, is a former incarcerated artist and co-founder of Right of return, United States, the first national scholarship dedicated to supporting survivor artists of the prison industrial complex. “We all know the story of Breonna Taylor, so I thought I’d make pieces like this to serve as callbacks,” Craig says. “It happens so much, we are conditioned.”

Former Right of Return Fellow Marcus Manganni also contributed to his 2022 article, End-to-end burners, at the show. An opulent chandelier made from 1,500 handmade shivs, it serves as a meditation on his time in solitary confinement on Rikers Island, New York’s infamous prison complex, which is closure planned for 2027. “I was thinking about prison architecture, just bodies on bodies on bodies,” Manganni says. “It’s about confronting the trauma of space.”

The works on display range from humanizing, silent photographs of New York City sex workers by Kisha Bari to a plaintive collection of paintings depicting mothers holding photos of their murdered children by Tracy Hertzel. “The politics associated with art can really inform the cultural zeitgeist,” says Trentmen. “It makes the message simple, clear and boils it down to impact and human experience.”

A series of free events will take place throughout the exhibition, from spoken word slams to activist panels. According to Miller, the project’s focus “combines policy advocacy, visual art, and performance art” to create a holistic rumination on social injustice for viewers.

Gutierrez adds, “Love is really at the center of this exhibition, even in its heaviness.”

- 29 million dreamsuntil May 6, Museum of broken windowsnew York