If you are unfamiliar with Roger Ballen’s photographs, google them now. Soon you will find yourself immersed in the singular world of the artist, a kingdom where rats roam and where monsters mingle with men and where everything is covered in filth. A thrill of excitement comes with the unease of looking at Ballen’s work, if only because the photograph keeps us at a reassuring and safe distance from any nightmarish place depicted in it.

What if this place was real?

It is now, in a sense. In Johannesburg, South Africa, Ballen has just opened a cultural space called the Inside Out Arts Center. Stepping through the building’s winding concrete entrance is a lot like stepping into one of his photographs.

The first things you’ll probably notice are the human and animal dolls set up in a series of eerie arrays across space. They belong to “End of Gamethe center’s inaugural show, which reflects the devastating legacy of the “golden age” of African hunting in the colonial era, when Westerners like US President Theodore Roosevelt and writer Ernest Hemingway made pilgrimages to the continent in the name of exotic game.

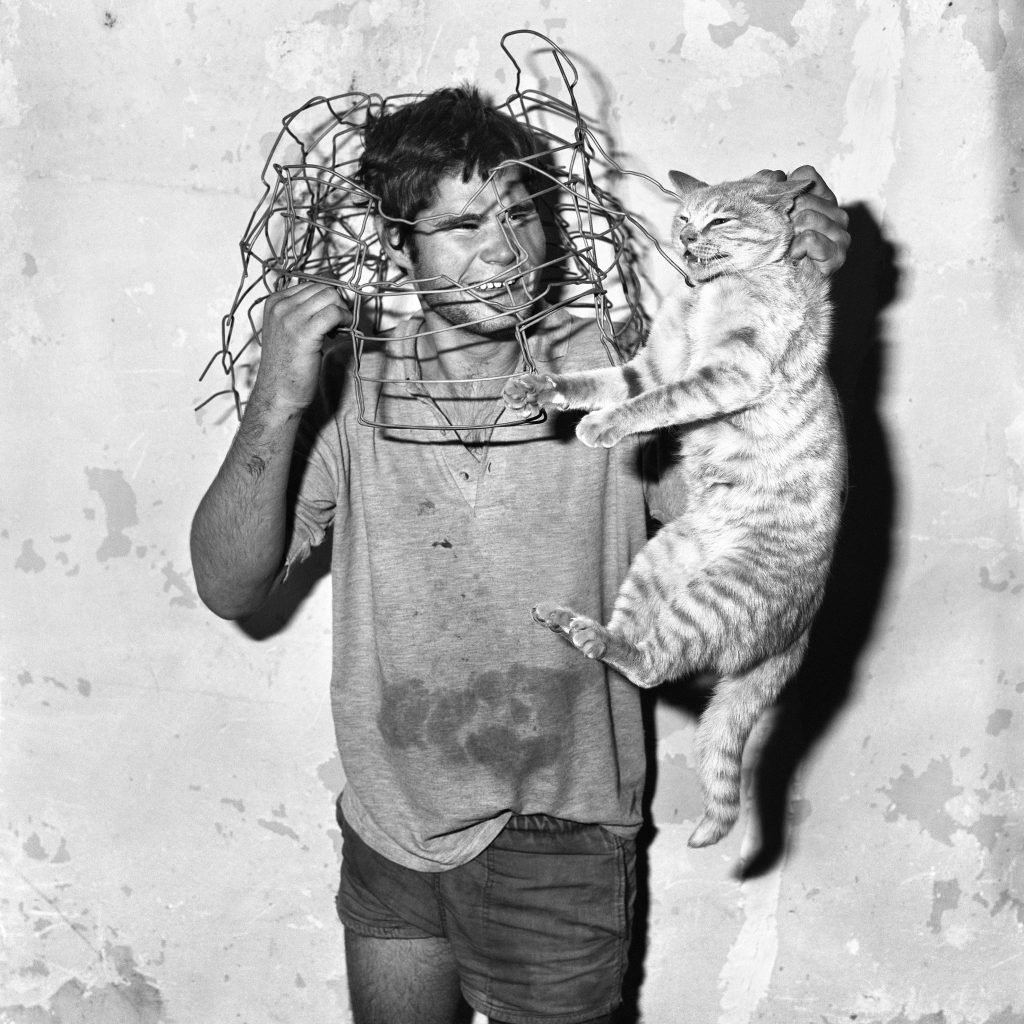

Roger Ballen Roger and the inner voices (2015). Courtesy of the artist and the Inside Out Center for the Arts.

With a mix of archival material and Ballen’s own work, the exhibition reflects his vision of the space as a museum, educational institution and studio. The artist has even arranged a set of guiding criteria for what to show in the space– a list of flexible rules which stipulates, among other provisions, that the art exhibited must relate to what it calls “ballenesque”.

Like “Lynchian”, “Ballenesque”, conveys a particular aesthetic, mood or psychological state. It’s hard to describe, but you know it when you see it.

“My approach to art is that the work should enter the subconscious faster than you can blink,” Ballen said. Artnet News in a recent video interview. “It doesn’t matter if you have an open or closed mind, it goes in there and is transformative.”

The artist, now 72, sat in front of a cabinet of trinkets that seemed at first odd, then oddly appropriate. On the lower shelves were figurines of Mickey Mouse, Tintin, and various other fictional characters that were decidedly not “ballenesque.” At the top rungs, however, were flabby rubber masks and a puppet that looked like a rabid rabbit with vampire teeth. I’d call them moderately “ballenesque”, but really it’s the combination of the two – cheap bric-a-brac sharing space with meticulously crafted horror items – that most captured the style of artist’s signature.

The Inside Out Center for the Arts in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Ballen, who co-represented South Africa at the Venice Biennale last year, has lived in Johannesburg for over 40 years now. The place has clearly had an indelible impact on him, even if it doesn’t necessarily show in his photos. Images don’t exist in a universe like the one you and I know, after all; South Africa may be where they were filmed, but the location could just as easily have been the basement of Mars or Satan or the unnamed, post-industrial setting of Lynch’s film. eraser head.

Johannesburg, he said, “is an extreme society; never think that it is not. It’s not an American suburb, I can tell you that.

But when asked if the psychological resonances of his work relate to aspects of his adopted hometown, Ballen insisted that his vision mostly reflected the recesses of his own mind.

“I found my niche here, in a way – the people, the places – and then I built on it, layer by layer by layer,” the artist continued. “At the end of the day, it’s hard to know what is documentary, what Roger Ballen’s imagination is. What is real and unreal?

“All of these things are combined in the work, which is part of the ‘Ballenesque’ aesthetic,” he said. “You’re not sure what’s what.”

Installation view of “End of the Game”, 2023, at the Inside Out Center for the Arts. Photo: Marguerite Rossouw.

Yet as much as Inside Out resembles Ballen, his mission is beyond him. He envisions the nonprofit space as a community hub, and he worked with his Johannesburg-based designer, Joe Van Rooyen, to create a structure that felt inviting to all.

“A lot of people who come here have never been to a museum in their life,” the artist said. (The building cost “a few million,” according to Ballen, and was funded by his own resources and a donation from a “private foundation,” which wished not to publicize its involvement.)

Education is a major priority for the center – special programs for high school students are planned – and its focus is more local than global. Another of the space’s guiding criteria is that the art on display “should have a direct or indirect connection to the culture, history or contemporary issues of the African continent”.

Roger Ballen cat catcher (1998). Courtesy of the artist and the Inside Out Center for the Arts.

Ballen’s work won’t always be on display, though it’s hard to imagine an exhibition ticking both the “Ballenesque” and “Relation to Africa” boxes without his involvement. No future shows are currently planned, and when asked about it, the artist said he and the team at Inside Out are still figuring out exactly what they want to show.

“End of the Game” currently doesn’t have an end date, but when it does, at least one of its animals will stick around. His name is Roger the Rat, and he is both a man and a rat; an unofficial mascot of the center and an alter ego of Ballen. (The artist made a character movie Last year.)

According to the artist, the human-sized creature recently burst into the center and has no intention of leaving. “He’s now a resident here,” Ballen said.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.