“I hope the problem will be felt,” said artist Sarah Miska (born in 1983) in her Los Angeles studio. “Sport is all about bridles, harnesses, bits, leather. My work may seem incredibly conservative on the surface, but it’s meant to be moderately sexual.

The sport in question is horse racing. The artist had recently put the finishing touches on a series of new paintings focusing on jockeys and racehorses for “High stakes“, his second solo exhibition with the Night Gallery in Los Angeles, which opens this weekend (July 8-September 9).

In recent years, Sacramento-born Miska has focused his paintings on images drawn from the equestrian world, reframing slightly oblique and random moments that occur in this highly regulated niche world: tightly braided horsetails fraying , a shiny riding muddy boots, a shiny bun that stands out. The paintings can be a light moment of comic respite from the exhausting and conservative aesthetics of the horse world.

“Quite frankly, equestrian sports can be boring because it’s so controlled, and those imperfect, imperfect moments are beautiful,” Miska said, “These images are also meant to be humorous, because if you consider the point of view of ‘a view jockey, tHello, you are in the most awkward, submissive and hilarious pose when they are horse riding.”

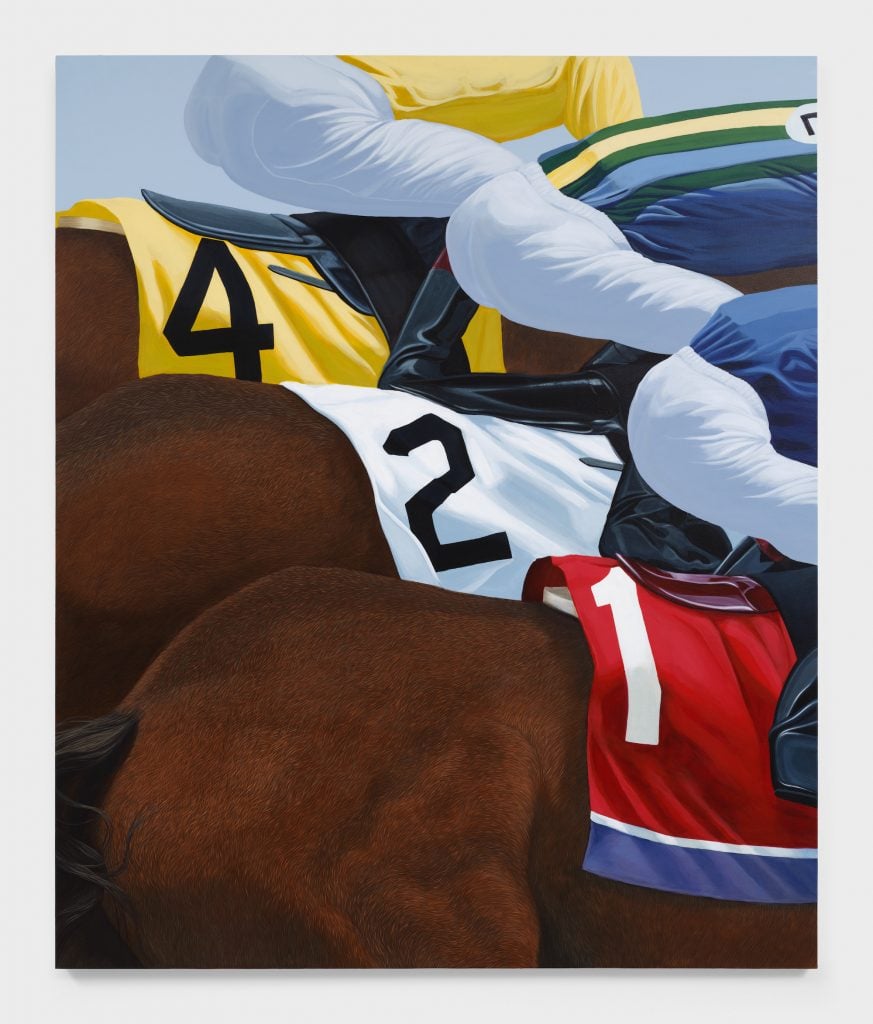

Sarah Miska, Trifecta (2023). Photo: Nik Massey. Courtesy of Night Gallery.

These paintings with a provocative wink have recently found a craze at aware galleries on both sides. Last year, Miska made her solo debut with Night Gallery and New York’s Lyles & King. His paintings are also part of the permanent collections of the Institute for Contemporary Art in Miami and the Long Museum in Shanghai.

Horses have long been a source of fascination and fantasy for Miska, who has described her young persona as a “budding horse girl”. Like many kids of the 80s and 90s, she was in love with black beauty and all things Lisa Frank, and dreamed of owning a horse. For many of her teenage years, she even took riding lessons, but the cost of the sport kept her from fully integrating into the horse world.

“My parents did their best to try to allow me to ride,” she explained. “They even bought these two incredibly terrible horses. One was too old to ride and was farting all the way down the track. The other would run with me and kick and thrash and lay on top of us. I think she was abused by her previous owner.

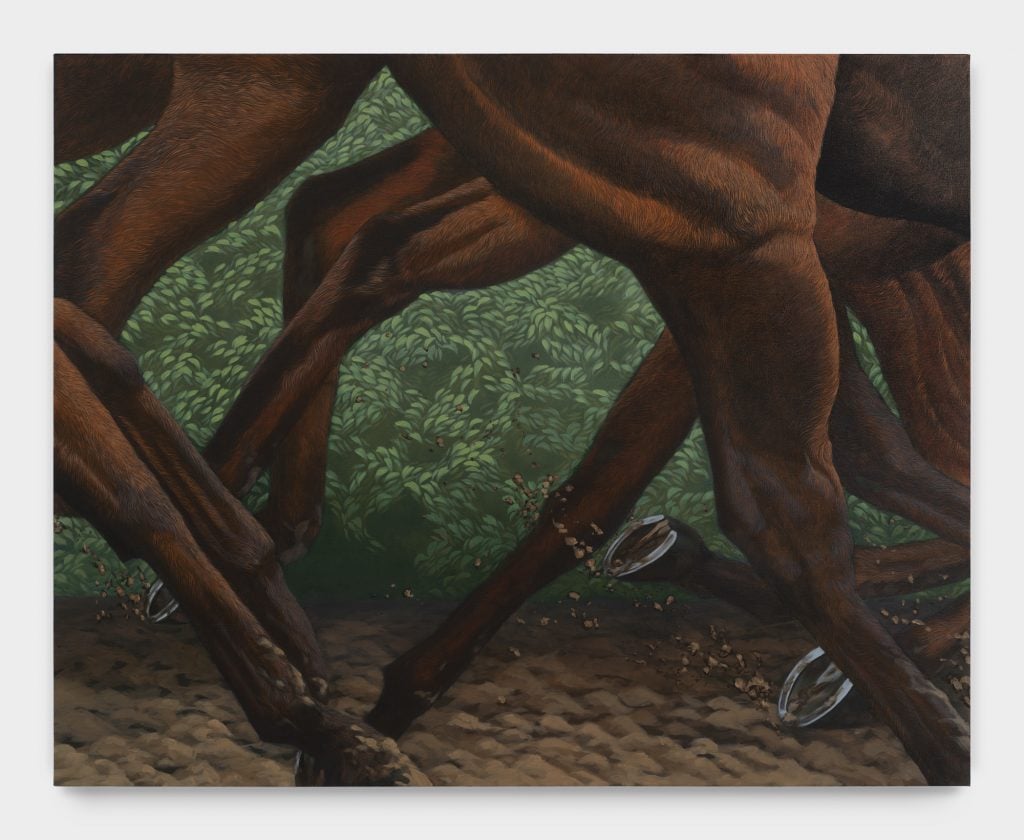

Sarah Miska, Red Plaid Jockey Silk (2023). Photo: Nik Massey. Courtesy of Night Gallery.

The horses, which had been purchased from a friend for around a thousand dollars (virtually free by equestrian standards), proved too expensive to maintain, and Miska’s parents sold the pair within a year. “It was all based on the fantasy – the fantasy of my parents being able to give that dream to their daughter and the fantasy nurtured in kids like me,” she explained, saying she “loved it, but my parents carried the burden of owning these animals.”

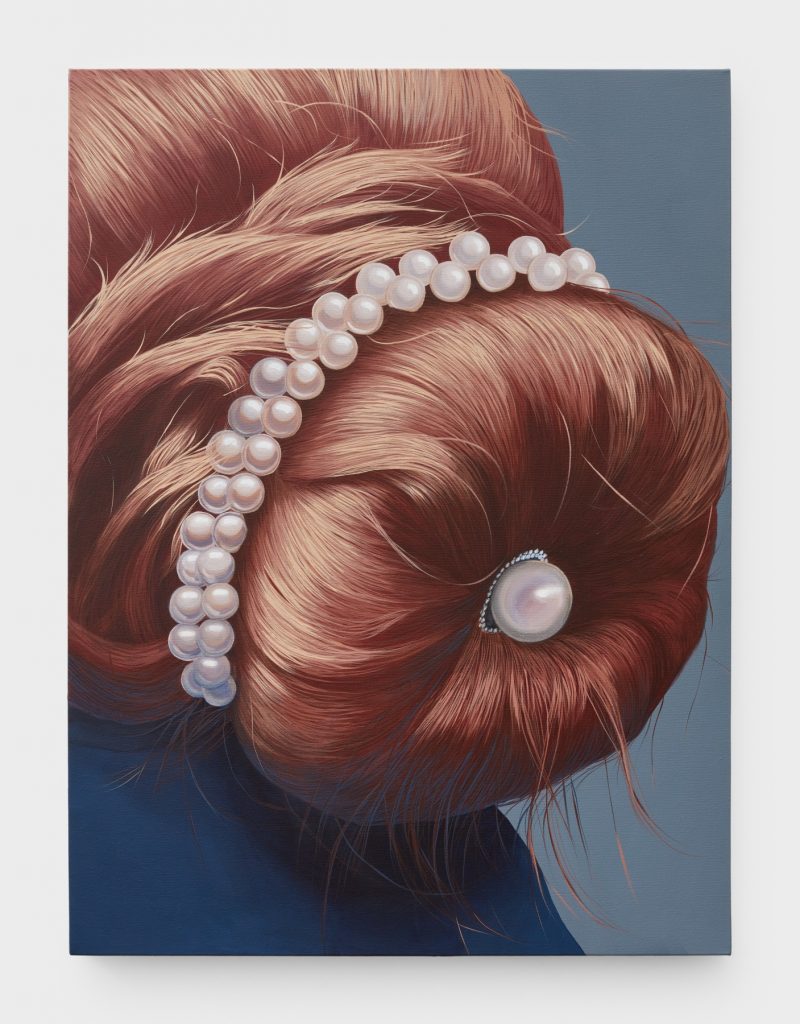

Miska, who received her MFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 2014, began experimenting with equestrian imagery a few years ago, given the similarities between the hairstyles of riders and the tail style of horse riders. horses.

“I was thinking about the buns and all the accessories that go with it, including the little hair net, the barrette and a bow, contrasting with the horses’ butts,” she said. “It was meant to be a little ironic, but I found myself diving deeper and deeper.”

Sarah Miska, Bet (2023). Photograph by Nik Massey. Courtesy of Night Gallery.

His new paintings in “High Stakes” delve into the risk and reward associated with the world of horse racing and explore the intense relationships between jockeys and owners, and jockeys and horses themselves. Several canvases in the exhibition focus on the colorful silk patterns donned by jockeys during races and allude to the age-old dynamics of power and stature. “Owners of these horses sometimes have specific bristles that belonged to their family generations,” Miska said. “So whoever the jockey is, they will be wearing this silk, literally representing the family.”

In Miska’s fascination with the magnifying details of hair and fabric, Italian artist Domenico Gnoli comes to mind. “Gnoli died so young. I wanted to see more of his work and decided I was going to try and build on that legacy,” she said. “His work did something very specific with texture. I love that it has to do with theater and the clothing movement.

Another similarity to Gnoli, she noted, is its use of acrylic paint. “I was trained in oil and I love it, but I’m a mother and when my child was very small I had limited time in the studio and couldn’t wait,” she said. declared. “Oil is so revered, but Gnoli worked in acrylic, and it’s nice to be affirmed.”

Sarah Miska, Pearl hair tie (2022). Courtesy of the artist.

In the realization of his paintings, Miska works with rigor and meticulousness. She pulls her images from social media, zooms and crops the images to small details she finds, and edits the images on her phone. She then squares her compositions in sketches or on the canvas itself, working with an attention to detail that is, Miska acknowledges, similar to the equestrian sports she explores.

When asked why she prefers found footage, Miska explained that she chooses not to attend race events at this time; she never competed as a child and now her absence is a more conscientious decision. It may not last forever, she said. There are some photos she may have to take herself — “horse assholes, quite frankly,” she said. “I think it’s the funniest thing and I love to laugh when I’m working but no one is posting these pictures.”

Linger for a moment on Miska’s works and another similarity to Gnoli emerges: the paintings overflow with a sense of evil. “Everything in the equestrian world is meticulous, regulated and controlled. There are power dynamics at play on so many levels. The rider controls a very wild, free and intense giant beast, which could kill a person. Still, the horse performs very well under this version of strict control,” Miska said. “Of course, this is related to my way of painting.”

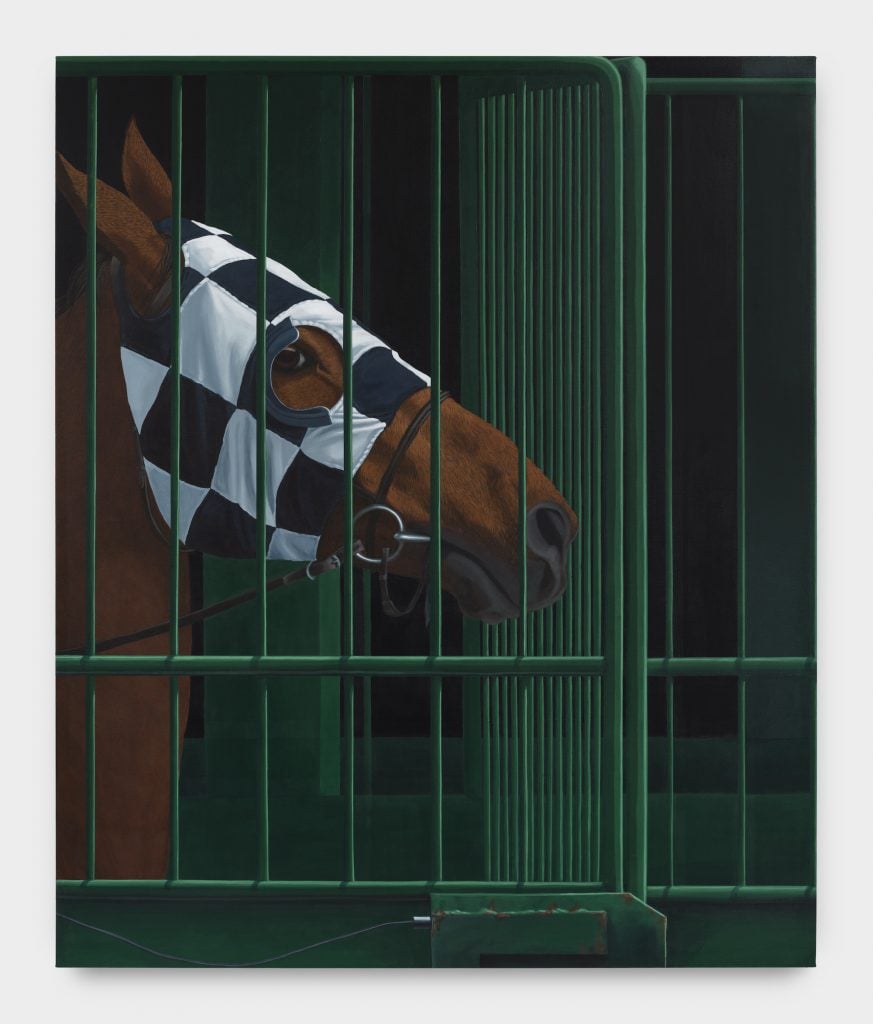

Sarah Miska, The starting gate (2023). Photo: Nik Massey. Courtesy of Night Gallery.

Miska admits there is an undeniable pull to the world of horse racing, a pull that compels her to engage in it. “I love the plot and I always want to be part of it. I feel like a voyeur looking through the outside,” she said.

However, she doesn’t always like what she sees. The painting Starting gate welcomes visitors to the exhibition at the Night Gallery. It shows a horse, still behind the gates of the racecourse. His eyes are frightened and alert in a way reminiscent of Henry Fuseli. The nightmare and Picasso Guerinica, but here frozen in total stillness.

“The poor horse is trapped and yet ready to burst,” she said. “All these animals know how to run, and yet they have to anticipate what is going to happen. It’s abrupt and aggressive, and I try to harness that energy in this work.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.