For an opening at the Hill Art Foundation in New York on April 21, artist David Salle has selected a selection of paintings and sculptures by 35 artists. Drawing on historical works by Peter Paul Rubens, Francis Bacon, Salman Toor and Cecily Brown, “Beautiful, Vivid, Self-contained” examines the role of juxtaposition in our experience of art. Below, read an excerpt from the essay Salle wrote for the show’s catalog.

The purpose of this exhibition is to question the nature of affinity in painting. What perceptions of painting—Upside down—link various works together?

How can we say that works of art influence each other? How is aesthetic DNA encoded in a painting; how is it transmitted and in what form?

What constitutes this influence? How to separate fashion, obvious and ephemeral, from the mysterious sowing of ideas which disperse like a puff of dandelion in the wind?

Are there pictorial inventions that cross historical divides to be reinvented in a totally different time and place?

Does an “aesthetic personality” exist and can it be recognized in another context? Can we say that a painting has a nervous system? What is the psychic cartography that underlies a pictorial attitude?

Perhaps the trickiest question of all: what is the relationship between intent and style, and is it quantifiable? Can artists of different styles (different surface attributes) relationship for them?

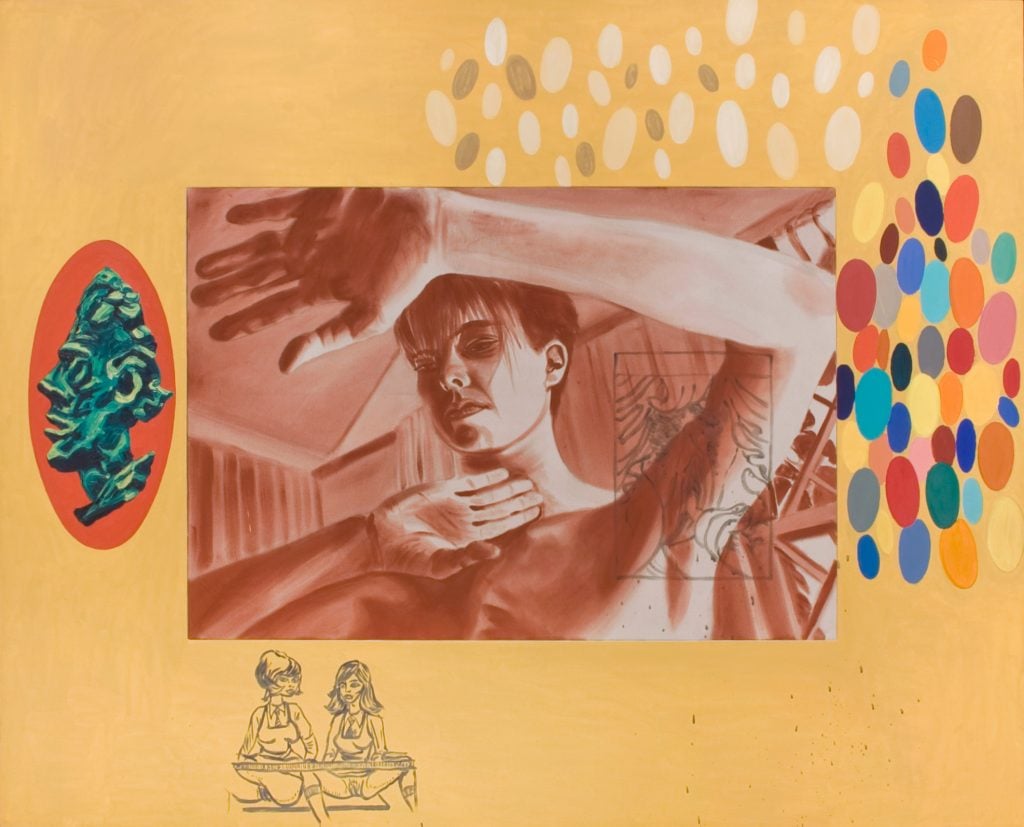

David Hall, Pavane (1990). © 2023 David Salle / VAGA at the Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Skarstedt, New York.

In a long essay published in the New Yorker in 2007, novelist Milan Kundera discusses the nature of accepted context versus actual influence. He surprises us by stating that he does not wish to be called an Eastern European writer. It may seem counter-intuitive in our current era of identity, but Kundera does not want to be a “Czech writer”. (He even chafes at being compared to Franz Kafka.) For Kundera, the whole notion of national identity as a literary category is misguided.

[I]If we consider the story of the novel, it was to Rabelais that Laurence Sterne reacted, it was Sterne who triggered Diderot, it was Cervantes that Fielding was inspired by, it was Fielding that Stendhal s t is measured, it is Flaubert living in Joyce, it is through Joyce that Herman Broch develops his own poetics of the novel, and it is Kafka who shows García Márquez the possibility of “writing differently”.

How do does aesthetic transfer take place? Let’s put the question in different terms. Two renowned composers on what they like and dislike about the work of previous artists:

I don’t believe in the distinction between tonal and atonal music at all. I think the way to understand these things is that they are the result of magnetic forces between notes, which create magnetic tension, attraction or repulsion. —Thomas Ades

It’s not so much how [Beethoven] gets into things that are interesting, that’s how he gets away with it.[4]—Morton Feldman

There are many ways to group paints; the categories most often used have little to do with the “inner energy” of a work. Easily accessible presumed affiliations are: generation (new painters) or geography (new painting in Canada); appearance, or “style”; technology; or demographics, otherwise known as identity. Now, only a fool would say that context doesn’t matter. Of course, the time, the place and the circumstances in which something was done matter a lot – they are sort of the markers of what is conceivable. But they fail to explain why certain things grab our attention, or why they affect us the way they do. A painting is more than the sum of its parts. It’s the the way in which these parts are assembled that move us, even if we are not aware of this dimension.

Anthropomorphizing paintings, projecting behavioral complexities onto them that one might apply to people, may seem like a kind of madness, but I’m willing to take risks. The images are all equally obvious; nothing is hidden. What happens in a painting happens, almost by definition, on the surface. How then can one say of a painting that it is obscure or enigmatic? It may be a matter of timing. There are objects that by design reveal themselves to all of us at once, and there are paintings whose stories unfold little by little, atonal piece by piece.

Cecily Brown, The use of blue in vertigo (2022). © Cecily Brown. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Genevieve Hanson.

Thomas Adès again, on the power of juxtaposition: “One thing becomes possible which makes another thing possible, which would not have been possible without it.

The bottom line: juxtaposition is the art of the possible. The visual art also adheres to Chekhov’s famous dramatic imperative: if there’s a gun in the first act, it must go off in the last. Some things in an array set the conditions for other things to happen. A painting can “import” elements from afar, from different aesthetic universes, if the painting itself has established a sufficiently elastic context. What was once impossible now begets the possible. The ways in which this is accomplished are myriad and unpredictable. So far stretch is fine. Stretchy is how we live now. What we want is an expandable Haggadah.

Can we say that the works in this exhibition speak to each other? What is the common language? Even though everything is a cultural construct, how one operates within that construct is the point of distinction.

To take just one example from our exhibition, consider the way Charline von Heyl lays the structural foundations of her painting for the unexpected; a surprising but seemingly inevitable conflict between different pictorial conceptions, like the last act of our drama. This thing – that image, mark, color or shape, that interval-requires This thing (fire burns the stick, water extinguishes the fire). Creating that sense of inevitability is art. It’s not just formalism, it’s the poetics of dynamism. Paint events are like notes in a melody, one note succeeding at specific intervals of sound and time. A sequence of atonal notes, although they are unlikely to sound melodic to us, can still have off notes. How can you tell? Even a baby can recognize nonsense words when he hears them. A six-week-old baby (if born to English-speaking parents) will recognize that “pilk” isn’t a word. There is a similar mechanism in painting, with the bewildering difference that it is the artist herself who must establish the grammatical rules, and also demonstrate in the painting how the rules are true. To make matters even more complicated, not all “rules” are equally productive, and not all applications of those rules have the same meaning.

The paintings in this exhibition, along with the sculptures, provide an opportunity to consider the aesthetic nature of grammar and syntax, and to note adherence to similar or overlapping grammatical rules. It’s not just that something looks like something else; it is a question of knowing how each image establishes its own notion of the uses of pictorial grammar. It is in the complex nature of painting: the artist relationship to this grammar is the source of their distinction.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.