It’s been ten years since Tate Britain last hung up its permanent collection, and in that time museums have had something of an accountability. Widespread public and critical opinion has demanded that institutions better reflect UK history, tackling the darker aspects of the nation’s past, from the legacies of slavery to the erasure of female artists.

The Tate’s redesign promised to do just that, not only by shaking up exactly what is on display (which exceeds over 800 works), but by adding context and renewed connections between artists, their work and the wider socio-political context. of the day. There is also a much broader understanding of what British art really means, encompassing a long history of immigration and asylum dating back to the Tudor era. “This is a chance not only to give space to more marginalized perspectives, but also to show that art is not created in a vacuum,” said Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson. at Artnet News. “It speaks in complex ways about the society we live in.”

This meant refining the chronological format of some forty rooms, to offer more thematic interpretations that could include seismic world events such as World War II or the Haitian Revolution, as well as the general feeling or collective psyche of a period, including mid-twentieth-century existentialism and Victorian New Urbanism.

Naturally, the demand for popular works such as David Hockney A bigger splash and John Everett Millais’ Ophelia taking first place is high. However, thanks to the introduction of new commissions that can recontextualize familiar pieces, as well as the inclusion of unsung but nonetheless brilliant artists, this new hang feels all the richer. Here, Farquharson tells us about five such examples, explaining, “We want to look beyond the frame, to see what’s missing as well as what’s in the picture.”

Pablo Bronstein, Molly’s House (2023)

This beautiful acrylic and camp ink drawing by Argentinian artist Pablo Bronstein depicts an 18th century ‘molly house’. These gay clubs were held in cafes and private residences in relative secrecy, and were often the subject of violent police raids at a time when homosexuality was punishable by death. Bronstein set out to reinvent this disturbing tale, using the architectural language of the time and infusing it with an entirely new sensibility.

“He chose, rather anachronistically, to portray molly houses as something extraordinary and proud,” Farquharson said. “Rather than a typical, understated Georgian facade, you have an extraordinarily flamboyant, image-filled Baroque building that offers something of one of the ‘greatest hits’ of erotic art, from Saint Sebastian to Eros.” Bronstein’s new commission shows the hidden side of life in Georgian London, a side that William Hogarth does not even dare to show in his satirical and moralistic prints of city life, which are also on display.

William Powell Frith, The day of the derby (1856-8)

William Powell Frith, The day of the derby (1856-8). Photo: Tate Photography.

This densely populated panorama celebrates the new possibilities for industrialization of Victorian Britain, particularly the advantages of rail travel, but it is also an exercise in social commentary. The scene depicts people from all walks of life who have gathered to watch the annual derby at Epsom Downs in Surrey, and is filled with vignettes designed to entertain, lavishly dressed ladies in horse-drawn carriages, circus performers and thieves at the car.

“It’s a great example of how the Victorians invented a new form of painting, where there’s no real distinction between popular culture and high art,” Farquharson said. “Artists are more reflective of contemporary life, often on a grand scale, with an emphasis on storytelling or drama. They also invented the blockbuster exhibition. When this painting was first exhibited in 1856 at the Royal Academy, people lined up around the block. A railing had to be erected to hold back the public and a police presence was required.

Frith’s photo also gives an idea of the birth of the Tate collection. “The building was originally called the National Gallery of British Art, meaning contemporary Victorian art of the day,” Farquharson added. “Much of what is on display in this area of the rehang is from the collection of gallery founder Henry Tate.”

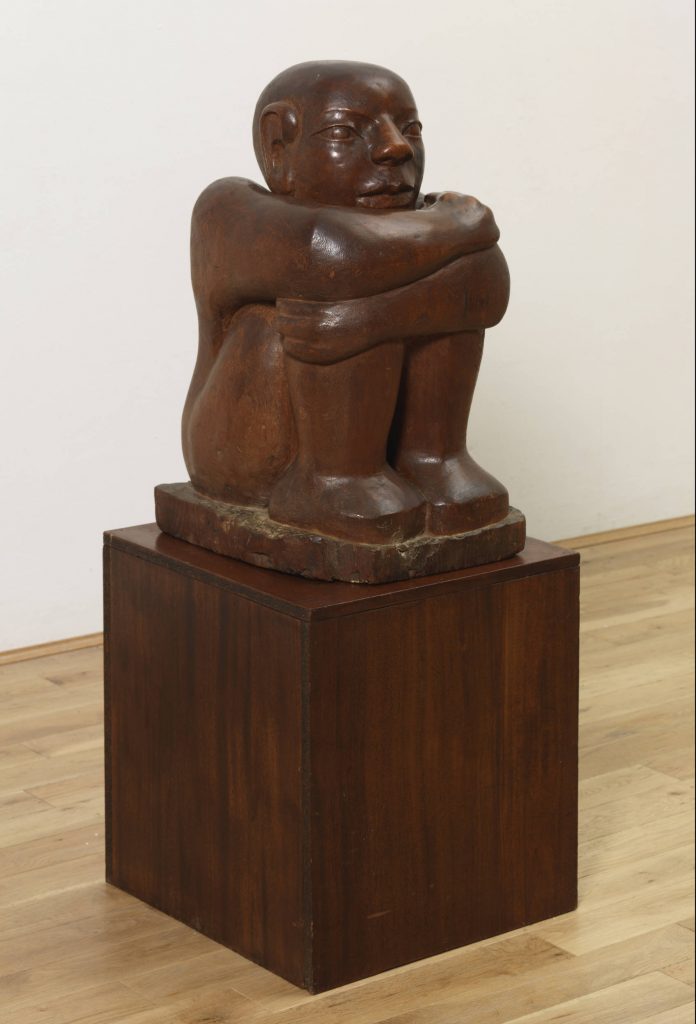

Ronald Moody, The viewer (1958-62)

Ronald Moody, The viewer (1958-62). ©The Estate of Ronald Moody. Photo: Tate Photography.

“In the post-war period, Europe and Britain are in ruins, traumatized by war and the horrors of the Holocaust. We are moving into a much more godless world and existentialism is becoming a very popular theory,” Farquharson said. “It was a time of enormous trauma, but also of renewed freedom, decolonization and immigration.”

Ronald Moody had already moved to London from Jamaica in the 1920s, but soon gave up a successful career in dentistry to pursue art in Paris in 1938. He returned to the British capital to escape Nazi occupation, sculpting stunning pieces of wood that embody what Farquharson described as “humanity’s frailty, both physically and psychologically.” Carved in teak, The viewer presents the figure of the artist as a watchful observer, crouching and wrapping his arms tightly around his body, as if to protect himself.

The smooth surface is nevertheless streaked with the marks of the sculptor’s tools, as well as a natural split in the wood running through the body as if in danger of splitting open. A dark, natural speck in the material also appears just below the character’s right eye, as if crying.

George Stubbs, Tedders And Reapers (1785)

George Stubbs, Reapers (1785). Photo: Tate Photography.

George Stubbs, Tedders (1785). Photo: Tate Photography.

“In the 18th century, parliamentarians were passing laws that allowed local landowners to ‘enclose’ or rather steal common land, which the working class relied on for food and a living,” Farquharson explained. “There was this perpetual idea that the possession of land was a distinguished and courteous pursuit, both at home and abroad, which is why artists such as George Stubbs created idealized notions of agricultural labor and even d slavery, as seen in the adjacent table. Dance scene in the Caribbean(1764-96) by Agostino Brunias.

In these two paintings by Stubbs, known for his bucolic scenes and animal images, the work seems almost tranquil, where well-dressed men and women happily perform their duty under the sun. These visions could not be further from the realities of backbreaking rural work.

“These are completely misleading fantasy images,” Farquharson added. “They were designed to spread a positive image of the landowner class and to make them feel better about themselves. As part of the rehang, we wanted to create a dialogue around these works, to show again what has not been seen. That’s why we featured Olivia Plender’s Set Sail for the Levant: A Board Game About Debt (for Social Satire) (2007), which uses a Monopoly-style format to show how cruel the realities of life were at that time. For most members of society, the odds are heavily stacked against you.

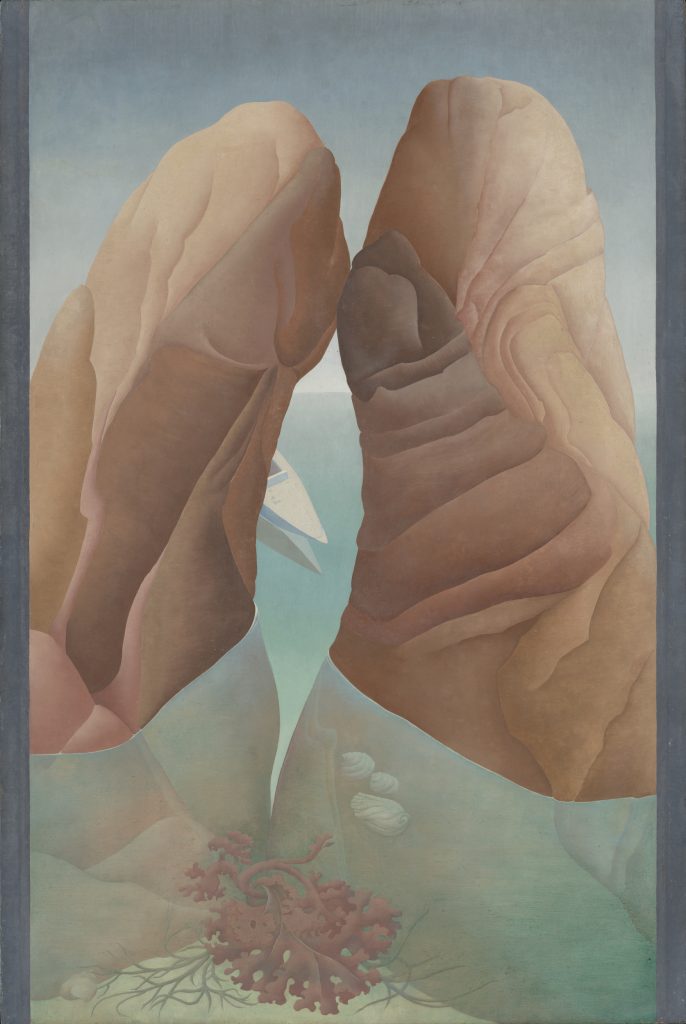

Ithell Colquhoun, Scylla1938

Ithell Colquhoun, Scylla (1938). ©Spire Healthcare, ©Noise Abatement Society, ©Samaritans. Pictured: Tate (Joe Humphrys).

According to Farquharson, “the rehang better reflects the contributions of women artists throughout Britain’s history, from the Tudor period to the present day. We feature modern masters including Barbara Hepworth [and the lesser-known] Ithel Colquhoun. The artist commissioned his own form of surrealism, inspired by the coastal surroundings of his adopted home in Cornwall. While other artists created implicit images of human sexuality, Colquhoun Scylla is almost graphic in its dualistic portrayal of the “female body as seascape”.

The title is a nod to a supernatural, monstrous creature from Greek mythology, which lurked in shallow waters to devour unsuspecting prey, including six of Odysseus’ companions. The two rock formations, which double as legs but also look somewhat phallic, frame a patch of seaweed, which replaces the public hair. The only presence of the man-made world takes the form of a small sailboat seemingly about to dock or perhaps crash into the rocks. Such a scene could allude to the unwelcome presence of masculinity imposed on mother nature. Whatever the interpretation, this painting is a fascinating example of women’s vital contribution to Surrealism in Britain and beyond.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.