The austere, slender room of the Dilston Gallery in the former mission church of Clare College in Southwark Park is one of London’s most spectacular spaces. Built in 1911, it was the first poured concrete building in the UK and was described at the time as ‘the finest modern church in south London’ – although the barn-like building, with its interior tall and austere, has more in common with early Italian Romanesque than 20th-century Modernist.

Since being taken over by Southwark Park Galleries in the early 1980s, Dilston has provided some of my most memorable artistic experiences, whether transformed into a shimmering green room of living grass by Ackroyd & Harvey, haunted by the lurking presence of the late Brian Catling or filled with a cavorting crowd of Anne Ryan’s fantastical colorful sculptures.

At Florence Peake’s REAL FACTUAL, installation view at Southwark Park Galleries, London (2023). Performers: Temitope Ajose; Iris Yi Po Chan; Katye Coe; Eve Stainton; Rosalie Wahlfrid; Nativeah White.

© The artist. Photo: Misha Haller

Today, this evocative place is beautifully brought to life by Florence Peake in Factual Reala multi-layered, performative, queer gesamtkunstwerk, which plays with and out of the ritual connotations of its environment to literally struggle with the history of painting. Seven huge unstretched canvases painted by Peake hang from the beams of the vaulted ceiling before being raised and lowered sporadically by six performers using pulleys and ropes. Hoisted up and down, hooked and unhooked, Peake’s giant, vivid paintings of plummeting multi-gender characters are brought to life still by being dragged, crumpled, wedged and used to cover, hide and shelter performers and sometimes audience members. . No longer passive objects to be contemplated, the canvases become active participants in the piece, sliding along the shiny white floor, getting dirty with the dancers, engulfing the audience and even scratching their surfaces to form a sonic backdrop to the action. .

Factual Real had its first incarnation in the heart of the National Gallery in London, where the proximity of all these old masters gave a supplement to the fluid action on Peake’s canvas. In Dilston’s dramatic and bare setting, the piece has now been extended and expanded, and the art story has grown even further. On a raised chancel in the form of a stage where the altar should have been, one of the dancers is squatting on her hands and knees. She rolls her paint-splattered boiler suit down to her waist, and another performer vigorously covers her upper body in paint. As cold paint splatters her bare flesh, a microphone is thrust into her face for her to read aloud from random handwritten fragments of canonical art-historical texts extolling Cézanne’s usual white male pantheon, Veronese, Titian, Tintoretto, Pollock and Al. These are actively transcribed by another interpreter from a stack of art books and catalogues, including several from the National Gallery.

sensual smudge

The symbolism of what is happening may seem basic, but like all of us, Peake has a complicated relationship with these great pictorial traditions. The messages therefore become more and more mixed as the application of the paint oscillates between wild gesture, sensual brushwork and burlesque humor. Is this body anointed, violated, pampered or ridiculed? Or all of the above? As the recumbent dancer calls the shots and barks orders at her text providers, it becomes less clear who dominates whom.

At Florence Peake’s REAL FACTUAL, installation view at Southwark Park Galleries, London (2023). Performer: Rosalie Wahlfrid

© The artist. Photo: Misha Haller

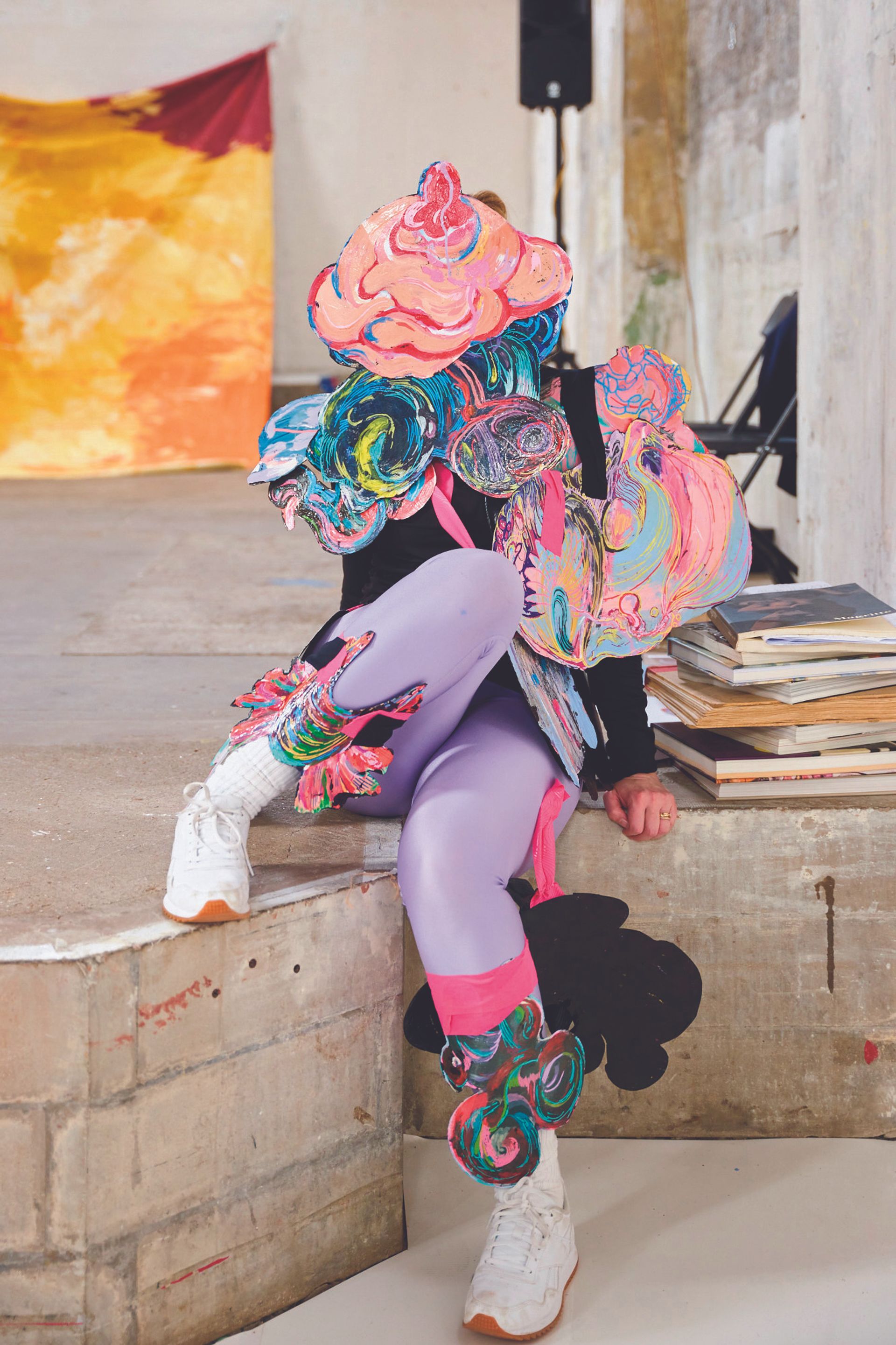

All along Factual Realover two hours, the boundaries between painting, performance, body and matter merge and merge across the emotional spectrum. At one point, a dancer appears with head and body encased in armored scale-like plates of brightly painted canvas. This eerie painting deity looks both malevolent and tragicomic as, weighed down and blinded by this encrustation of impasto medallions, which Peake described as “chunks of grief externalized as condensed matter,” they navigate a tortuous and slow route around the edges of space. Would one then be meant to ridicule or pity another figure who stumbles and stumbles across the length of the building, entangled in paint stretchers whose canvases have been ripped off?

Florence Peake, PromulgationRichard Saltoun Gallery, May 30-July 15

There are more conversations with the live work taking place across the city in a solo exhibition of Peake’s new paintings, sculptures, installations and works on paper at the Richard Saltoun Gallery, aptly titled Promulgation. Here, unstretched canvases form large sculptural installations while a pair of emaciated angular figures in wood and plaster bow in contemplation before a number of pictorial medallions that have now migrated from being part of the costume of a dancer to be mounted on the wall as works in their own right. LAW.

Once again, in Florence Peake’s fluid and changing world, categories dissolve, nothing is fixed or finite and anything and everything is possible.

• Florence Peake: real factualSouthwark Park Galleries, London until July 2, then on tour at Fruitmarket, Edinburgh in October 2023 and Towner Eastbourne in early 2024; Directed by Florence Peake – Richard Saltoun Gallery, May 30-July 15