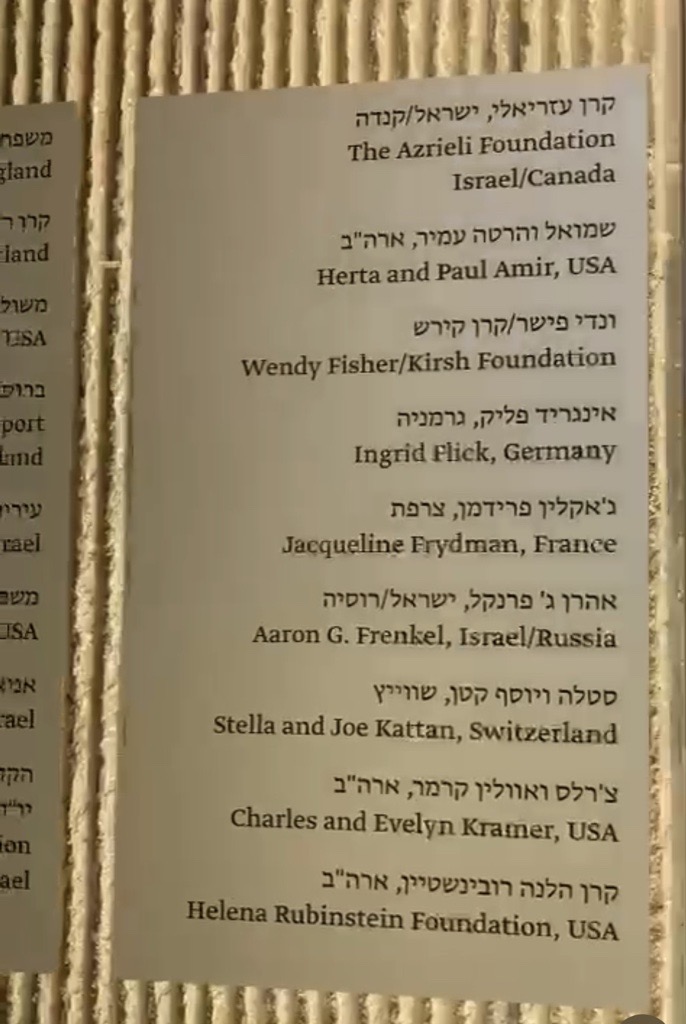

The names of some of the world’s most distinguished and wealthy Jewish families – Rothschild, Safra, Lauder, Ofer, Nahmad – are prominent on a wall in the foyer of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. They are the founding patrons of Israel’s leading cultural institution.

Among them is Ingrid Flick, who inherited by marriage the fortune of Friedrich Flick, a convicted Nazi criminal and Germany’s richest man at the time of his death in 1972.

Ten years ago, Flick, who heads a foundation named after his late father-in-law, donated €600,000 (about $670,000) to the Tel Aviv Museum’s Prints and Drawings Gallery. The funds were sent through the German Friends of the Tel Aviv Museum, a fundraising group, arriving in three installments of €200,000 in 2013 and 2014, according to a Flick Foundation spokesperson in Düsseldorf, in Germany.

The contribution, originally reported by Artnet in 2014, resurfaced in light of another controversy over Nazi wealth at the museum. Last week he canceled an upcoming Christie’s conference after the auction house fired of Jewish groups for its sale of Heidi Horten’s jewelry. Horten’s first husband, Helmut Horten, was a Nazi profiteer who expanded his department store empire by buying up Jewish businesses under duress as part of Germany’s Aryanization program.

While some applauded the museum’s decision to cancel the conference, David de Jong, the book’s author Nazi billionairessaid it was an empty gesture because the museum itself had accepted donations from German patrons, including Ingrid Flick, whose wealth could be attributed to Nazi crimes against the Jewish people.

“I find the hypocrisy of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art staggering,” de Jong said last week. “It’s not like the museum is taking its name off the lobby.”

This sparked scrutiny of the museum’s acceptance of Flick’s donation. When contacted for comment, a museum spokeswoman said the gift had been accepted by former management.

“The current management of the museum is looking into the situation thoroughly,” a spokeswoman for the museum said in response to Artnet’s inquiry. “They will assess their position regarding this donation and take appropriate action based on their assessment.”

Ingrid Flick’s name is among the founding partners of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Courtesy of David de Jong.

Since Flick made the donation, museums around the world have begun to grapple with their benefactors’ source of wealth, and many have eventually cut ties with problematic patrons. Chief among them are the Sacklers, whose names were erased from major museum buildings and galleries in the US, UK and Europe after their role in the opioid crisis came to light.

“As someone with an affinity for art and a collector of modern art, it has been a personal desire of mine for many years to support art that is also open to the public,” Ingrid Flick said in a statement. statement to Artnet on July 13. “The Tel Aviv Museum of Art was therefore just one of many institutions to which I am happy to donate. This donation and my personal motivation to contribute to the Tel Aviv Museum of Art has nothing to do with my late husband’s family history. Such speculation only serves to insult the valuable work of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, which I will happily continue to support in the future.

De Jong said this week that this type of philanthropy is an example of reputation laundering.

In the epilogue to his book, de Jong recounted his shock after seeing Flick’s name on the wall of the Tel Aviv museum. Ingrid was the third wife of Friedrich Karl Flick, whose father, Friedrich Flick, was “the most powerful and ruthless of all German industrialists, who was condemned at Nuremberg and became the richest man in Germany at three different times,” de Jong wrote. Friedrich Flick used slave labor in his factories and mines, including 2,600 Jewish women brought from concentration camps. After the war, Flick fought to reject any claims for compensation – just like his son Friedrich Karl, according to de Jong.

“[Ingrid Flick] never made any sort of reckoning with the Third Reich roots of his inherited fortune,” de Jong said.

David Schaecter, president of the Holocaust Survivors Foundation USA, an outspoken critic of the Horten auction and the Christie’s conference, said he was glad the Tel Aviv Museum is considering Flick’s donation. “I hope it removes the names of the heirs to any Nazi fortune from its walls,” he said.

More trending stories:

Ornate Viking-era relic found by UK metal detector could fetch over $30,000 at auction

Art Industry News: More Museums Walk Away From David Adjaye After Allegations + Other Stories

Israeli first-grader stumbled across 3,500-year-old Egyptian amulet on school trip

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.