Time is running out for Ricco Wright, the owner of the Black Wall Street Gallery in Chelsea.

In the Last year, he received eviction threats from his landlord and warnings from attorneys representing two artists who say they owe nearly $100,000 in unpaid commissions for the sale of a half- dozen paintings.

There is two separate GoFundMe pages dedicated to employees Wright allegedly rejected, and a page repeats with over 45 comments from current and former associates debating whether he is a scammer. A online petition accumulated dozens of signatures from affected people whom he abused and failed to pay artists and employees.

Wright does not dispute several artists’ claims that he owes them money, but says it does not constitute wrongdoing. “I am ready to pay all these debts,” he told Artnet News. “It’s very difficult to do that when people are spreading false information.”

Interviews with more than a dozen artists and former employees, as well as a review of several emails and texts, illustrate how a man claiming to uplift the black community appears to have wronged various artists.

A young artist named Brandon Tellez, who had exhibited with the Black Wall Street Gallery since it opened in New York in 2020, took a trip to Florida a few months ago thinking a $7,500 payment from Wright was due. come. But the check never came.

“I told him I depended on that money to get back to New York. He didn’t seem to care,” Tellez recalled.

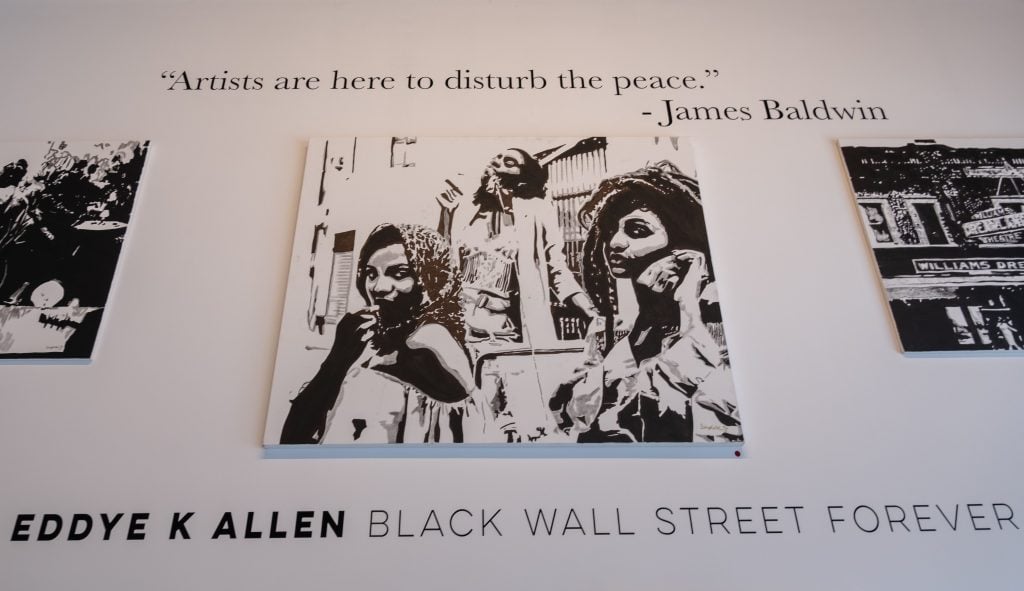

A gallery featuring black artists displays artwork during June 19 celebrations in the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, site of the 1921 race massacre, on June 19, 2020. (Photo by SETH HERALD/AFP via Getty Images)

Another artist, who claimed she owed $12,000 for an exhibition in February 2022, said her requests for payment had gone unanswered, despite a contract stipulating payment would be made within 30 days. (The artist asked to remain anonymous as she did not want her name associated with the gallery.)

Last spring, the gallery did not answer his questions about unsold paintings. Then an art manager contacted her with the address of a Manhattan Mini Storage where she would find her unsold items. Inside were not only the lost paintings, but seven others that Wright had claimed to have already sold. (Artnet News saw a photo of the storage unit.) Their buyers asked the artist in emails why the artworks they had purchased had still not been shipped for almost six months. after the sale.

The artist eventually parted ways with the gallery without recovering the money Wright owed her. She wanted to end the business relationship. “My last sentence for him was leave me alone,” she says.

Wright offered defenses of his actions in the communications to some of the artists.

“I am not running a Ponzi scheme. We had a bad quarter because of the two exhibitions that didn’t go well,” Wright said in January texts to another artist to whom he owed $12,500.

When Japanese painter Mayoumi Nakao informed him that she planned to sue him for not paying the approximately $35,000 he should have, he said he was working to repay her. After criticizing Nakao for sharing a Reddit post in January who accused him of being unethical and abusive, Nakao responded, asking where the lie was in the post.

Wright replied, referring to the allegations it contained: “I am not a predator. I’m not a sociopath either.

In February, artist Lawrence “LAW” Parker sued Wright in New York State Supreme Court, claiming the gallery owner owed him $79,500 for eight paintings, including one that Wright allegedly undersold without permission.

The gallery owner told Artnet News that he had received no legal notice for either case. “Businesses face challenges,” he said. “That’s not to say the gallery is scum of the earth because it’s going through a tough time.”

The North Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, known as Black Wall Street, was burned down by a white mob in 1921, killing more than 300 people. Photo by Alvin C. Krupnick Co. for The Associated Press, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Wright first opened the Black Wall Street Gallery in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 2018. The gallery was located in the Greenwood District and commemorated African-American families who were massacre in the 1920s by white rioters.

Wright became a local celebrity and chose to run for mayor based on a promise to uplift the black community. But his 2020 campaign ended when a local artist accused him of sexual battery. Wright denied the allegations, saying he was struck down the night of the alleged attack. No criminal charges have been filed.

In a Facebook post announcing his withdrawal from the mayoral race, he wrote that the allegations had become too distracting from the issues. “And on a personal level, I am committed to changing my behavior to make sure I respect boundaries and live a righteous life,” Wright wrote. “I am a single father who strives to be a great example for my two daughters.”

A few months later, in October 2020, Wright moved to New York and reopened the Black Wall Street Gallery. It quickly made headlines again.

Someone vandalized the gallery window three times in one week.

“A literal whitewash,” Wright told a reporter, and called on police to investigate the graffiti as a hate crime.

Police then arrested William Roberson, a black man, who openly admitted to vandalizing the storefront. But the attack was not racially motivated, he said on instagram; this was because he felt that Wright had allegedly made his wife uncomfortable with what she perceived to be sexual advances.

Wright said THE New York Post: “It had nothing to do with his wife.” He added: “I believe this young man is struggling with mental issues.”

Wright’s most recent financial troubles appear to have started with his move to a two-story gallery on West 25th Street in Chelsea, located near top galleries like Gagosian, David Zwirner and Pace.

But prestige comes at a price, and Wright told artists he had to pay more than $30,000 a month in rent. “So each exhibit must sell at least $60,000 to cover rent,” he wrote to an artist in August 2022. “But honestly, each exhibit must sell at least $100,000 to cover rent and other expenses.”

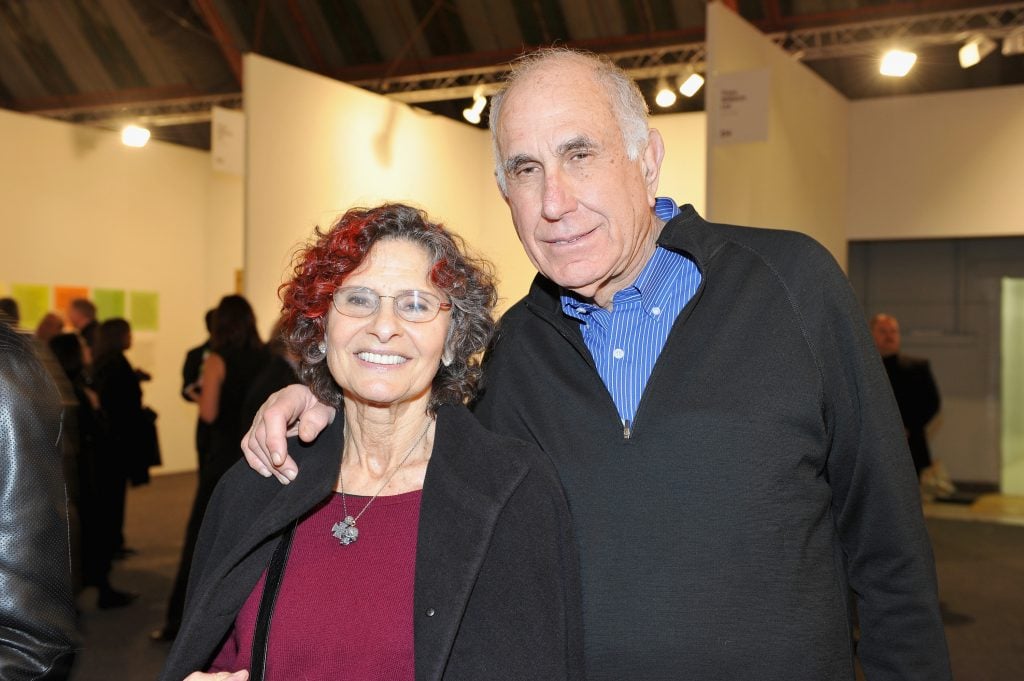

Collectors Susan Hort (left) and Michael Hort attend the 2017 Art Los Angeles Contemporary opening night at Barker Hangar on January 26, 2017 in Santa Monica, California. Photo by Donato Sardella/Getty Images for ALAC.

It was a difficult task for most of the artists on his list, whose paintings only sold for a few thousand dollars each. But the gallery was supported by a few influential collectors, including Susan and Michael Hort. Printing magnates frequently purchased works, and Susan often promoted the gallery on her Instagram account.

Four former employees said Wright described the gallery to collectors as a non-profit organization, although Wright denied those claims.

Public records show an application for nonprofit status was approved in 2019 for an entity known as Black Wall Street Arts; however, the designation was automatically revoked in 2021 because the organization never filed its financial disclosure forms with the government. The Chelsea Gallery is registered as a limited liability company, according to Wright.

Inside the gallery, Wright would describe the Black Wall Street Gallery as if it were a startup.

“I thought it was a commercial gallery,” said Nina Mdivani, the gallery’s former senior director. “I have never had access to the gallery’s accounts or financial statements. Although I have repeatedly asked these to track their earnings.

Wright offered all employees, from art managers to executives, a monthly salary of $4,000, according to Mdivani, who said none of the workers had signed a formal contract with the gallery despite demands for contracts .

A few days before last Christmas, Wright fired all gallery staff, blaming two previous exhibitions for his financial problems. He promised to pay the remaining salaries in two installments and full refunds in the near future. “Thank you and happy holidays,” he added.

FFormer employees were skeptical that undersold exhibits were the only problem. Three have suggested that Wright used gallery funds to subsidize his work trips to Vienna, Berlin and Art Basel Miami Beach, as well as his Soho House membership, which he used to woo artists, and his unpaid debts. to other artists. Several artists and employees said Wright was looking to rebrand his gallery as a membership club catering to creatives, noting that he would take potential investors on tours of the gallery to convince them of his vision.

Wright told Artnet News he was confident in the Black Wall Street Gallery’s ability to pay its debts, although it might not make financial sense for it to stay in Chelsea. “We have encountered financial difficulties and are working on our way back,” he said.

“I think he got in over his head,” Tellez said. “Ricco wanted to build something so big that he dug himself a deep hole.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.