In Sally Cook’s 1975 canvas Self-portrait five images, the painter and poet depicts herself in different decades of her life – one in the then present and two in the past and future. The younger version of the artist is the only one not shown standing in her mother’s living room; rather, it is framed by a window: literally outside, looking inside.

“She’s the artist,” Cook, now 91, recently said of her young painted persona. “She’ll never come in.”

For a long time, this is how Cook perceived herself in relation to the art world: an outsider. She felt this in the 1950s, as a woman trying to carve out a place in New York’s predominantly male 10th Street scene, and again after returning to her hometown of Buffalo, New York in the 1960s, when the city’s insularity art institutions ignored its charming domestic figuration as a craft.

“I was treated like a non-person,” she said, the chip still on her shoulder.

Self-portrait five images is one of the many stars of “Where Fantasy has flourished, Painting and Poetry since the 1960s,an excellent study of Cook’s work through July 8 at the Eric Firestone Gallery in New York. Included is work from three decades of her career – a period that has seen her change style, city and focus. It develops on a exposure which opened at the University at Buffalo Art Galleries in mid-March 2020, only to be closed by the COVID-19 pandemic a few days later.

For Cook, who hasn’t benefited from many breaks, the abrupt closure of the 2020 exhibition must have come as a devastating quitus in his career. But now, thanks to independent curator Julie Reiter, who curated the current exhibition, Cook has finally gotten the victory lap she’s long deserved. “I hope this helps cement his legacy,” Reiter said.

Sally Cook, Self-portrait five images (1975). Courtesy of the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery.

When Cook last showed in New York, she was living there, renting a room on the Bowery and frequenting the Cedar Tavern and The Club, where art stars like Franz Kline and Willem de Kooning held court. Cook shared these artists’ interest in pushing the boundaries of abstraction, but not their egos or ambitions.

“I was interested in abstract expressionism as an idea, but the thing is, nobody wanted to talk about it! They just wanted to get from 10th Street to 57th Street as quickly as possible,” she said, referring to the cluster of old-guard malls that have congregated downtown.

After a pair of group exhibitions, Cook had his first solo exhibition at the Phoenix Gallery on 10th Street in 1959, then a second in 1961. Two abstract paintings from this last exhibition are currently on display at Eric Firestone: Opalescence And Liver of Roses, both completed in 1960. They recall the floral palette and emotive gesture of Joan Mitchell, but with a compositional density that Mitchell did not adopt until later in his career. Cook, for his part, never left an inch of canvas unfilled.

Sally Cook, Opalescence (1960). Courtesy of the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery.

It wasn’t always a popular choice. She said it was these same stylistic flourishes that in the 1950s and 1960s annoyed her contemporaries, especially those indoctrinated by the rigor formalism of Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. “Why do you paint to the edge of the canvas? Why do you use so many colors? she remembered contemporaries asking her for her work, her voice inflected with imitative paternalism.

“Sally felt that there were rules in place – very dogmatic rules – that she had to follow, and there was no room for discussion about how to push those boundaries,” explained Reiter, noting that Cook has “always been someone who questions boundaries and borders.

After a third solo effort at the Camino Gallery—another 10th Street rendezvous—Cook decamped from Manhattan to Buffalo. “I learned a lot,” she said of her New York experience, “enough to know I wanted to leave.”

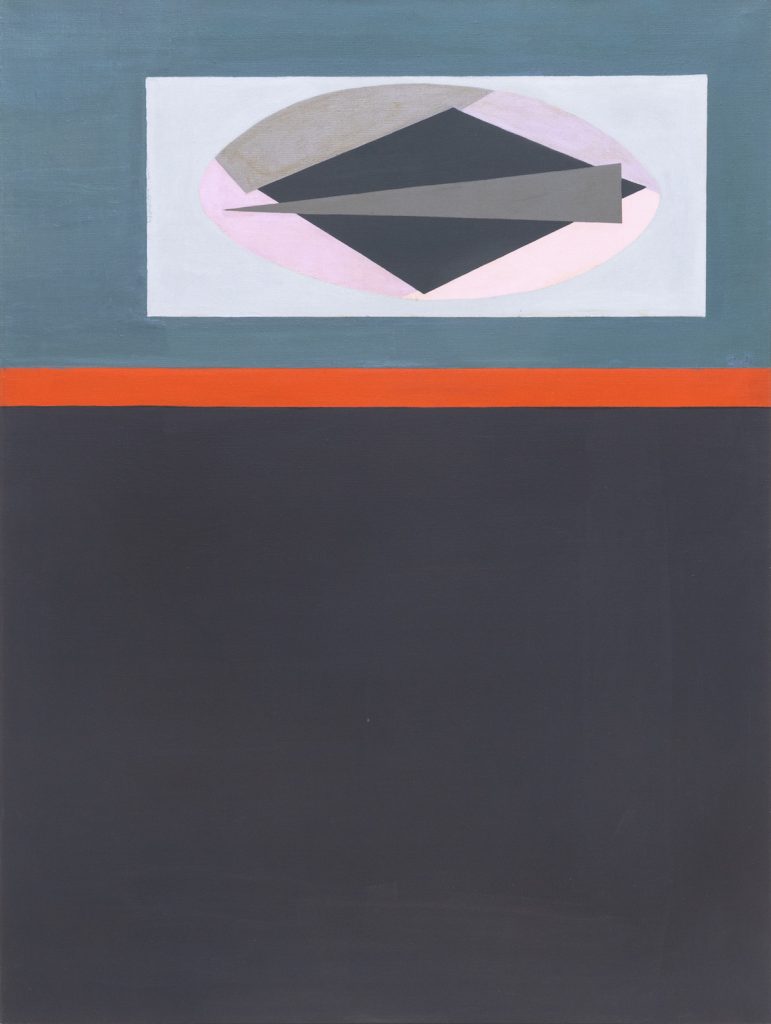

Sally Cook, The bird that died from oversleeping (1967). Courtesy of the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery.

Back home, the artist’s work became sharper and tighter, evolving into hard-edged geometric abstractions. Blocks of graphic color filled his canvases, but even then you could see his penchant for figuration beginning to show. Take The bird that died from oversleeping (1967), also included in “Where Fantasy Has Bloomed”.

Based on a recurring dream told by a friend, the painting features stacked gray triangles at its top – a blackbird deconstructed into shapes. Below is a band of red paint – a “thin line of rage”, Cook called it. The painting is, both in color and tone, one of the artist’s darkest works.

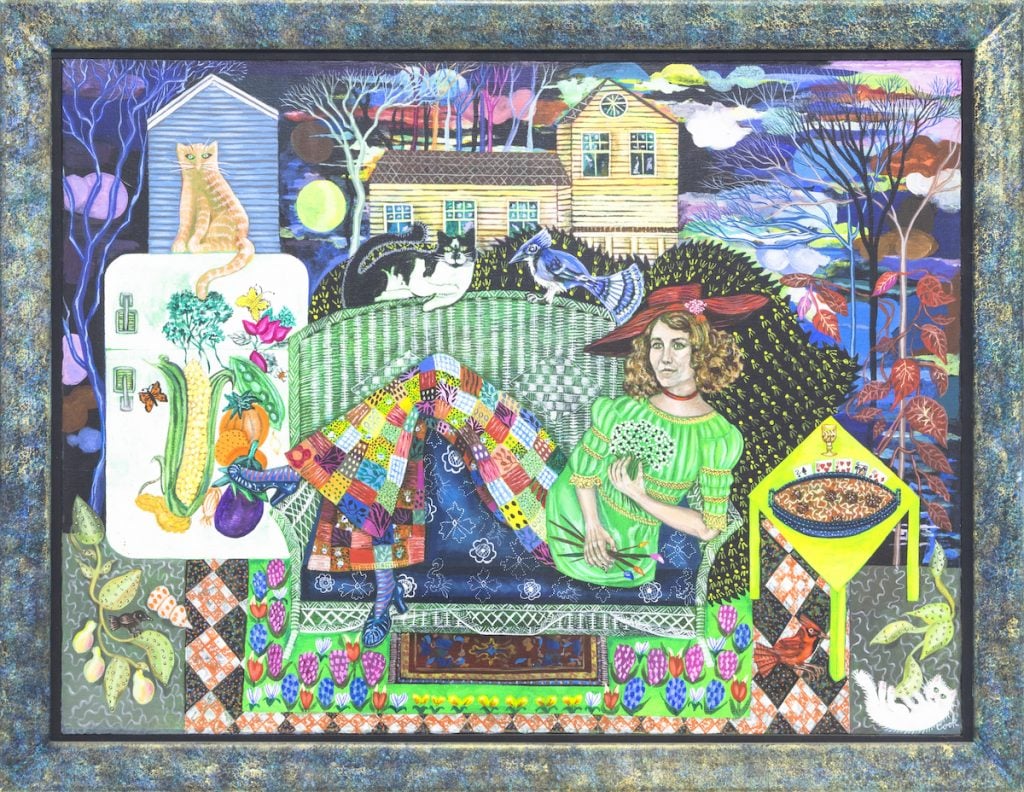

In the early 1970s, figuration entered Cook’s practice fully; as well as a new sense of humor and intimacy. She began painting pets, friends and members of Buffalo’s art scene, often situating her subjects in funky clothing amid a rich array of personal effects: favorite furniture, books, rugs, art . Like the theatrical paintings of Florine Stettheimer (who was also a poet), Cook’s portraits double as studies of class codes and social etiquette.

Cook also embraced his own admitted struggles with perspective, flattening his scenes to emphasize their strangeness. In a 1970 commissioned portrait of collector Charles Penney, founder of Buffalo’s Burchfield Penney Art Center, the subject dominates his most prized possessions, including Josef Albers, Alexander Calder and Robert Goodnough. (Here again, Cook is painted standing outside, framed by a window of Penney’s house.)

“Flatness is, to me, like a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” Reiter said. “There is intentional deceit and insolence. It’s linked to his interplay between surface and depth. You think you see all of her work on the surface… and yet there are so many layers and references and this absurdity and weirdness in the way she captures the human experience.

Sally Cook, Gypsy At The Carnival Of Life (1976). Courtesy of the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery.

Cook’s endeavors of this period apparently had little in common with his geometric experiments of earlier years, let alone the integral abstractions of his time in New York. While these earlier works had only a distant and symbolic relationship with the world, his figurative paintings seemed almost defiantly idiosyncratic, the work of an artist whose search for meaning has led her through the looking glass – and the guarded enclaves of Capital A’s art world – into her own life.

She began to center herself in the frame – often literally, in the form of self-portraits, but sometimes also slyly, through symbols encoded with personal meaning. Sometimes she even included depictions of older paintings in new ones. This is the case with his 1983 painting God gave a crow a piece of cheese; He turned around and gave me this. Named after a Chekhov’s History, it features Cook surrounded by examples of past work, many of which are painted from memory.

“I stuffed into my painting as many of my works as I could remember,” Cook said in a story told by Reiter. “As their colors and shapes jostle and create community, I am alone. No one ever gave me cheese. A piece of cheese may satisfy a crow, but this crow knows not to depend on it.

Sally Cook, God gave a crow a piece of cheese; He turned around and gave me this (1983). Courtesy of the artist and Eric Firestone Gallery.

“Sometimes she’ll represent herself, sometimes she’ll represent her paintings, but that’s all her,” Reiter explained. “I think it was about legacy and canon and I was wondering if her work would end up in museums, or if she just needed to keep showcasing her own work, keep painting it to say: “Look what I’ve been producing.'”

Cook pulled off the same trick with Self-portrait five imageswhere his first abstractions blue green forever (1960) and A flag for Delores IV (1965) are shown hanging on the pink Pepto Bismol walls next to different versions of herself. (These same paintings flank Five Pictures at Eric Firestone too – a nifty installation tip from Reiter.)

While Cook can sympathize with the younger image of herself in this painting, it’s the older one she most resembles now, and not just because of her age. With his hands at his sides and his eyes fixed on the viewer, the elder figure is firmly—Finally-inside.

When asked if she feels that way now, with a survey of her life’s work in the city where she started, Cook simply said, “Yes,” then stopped. “Thank God I lived long enough to see it!” she added, half joking.

“Sally Cook: where fantasy has flourished, painting and poetry since the 1960sis on view until July 8 at the Eric Firestone Gallery in New York.

More trending stories:

A couple renovating their kitchen in Denmark found an ancient stone engraved with Viking runes

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.