Fairy tale by French author Charles Perrault from 1695 donkey skin is a story of how women sometimes have to become monstrous to survive. A beautiful queen’s dying wish is for her husband, the king, to remarry a woman like her.r and talented like her. The only match for his late wife – the king discerns – is the couple’s own daughter. Led by her fairy godmother, the horrified princess disguises herself as a donkey to avoid detection and flees to another realm where she finds safety. Working on a farm, the princess, still dressed in the skin, is so unsightly that the townspeople nickname her Donkey Skin. In the privacy of her lodgings, however, the princess reverts to her royal ways, when a handsome prince eventually discovers her.

This disturbing story is the source of the work of Italian artist based in New York Bea Scaccia. (born in 1978, Frosinone, Italy) new body of work, paintings that explores the tensions and interactions between beauty and monstrosity, gender and identity.

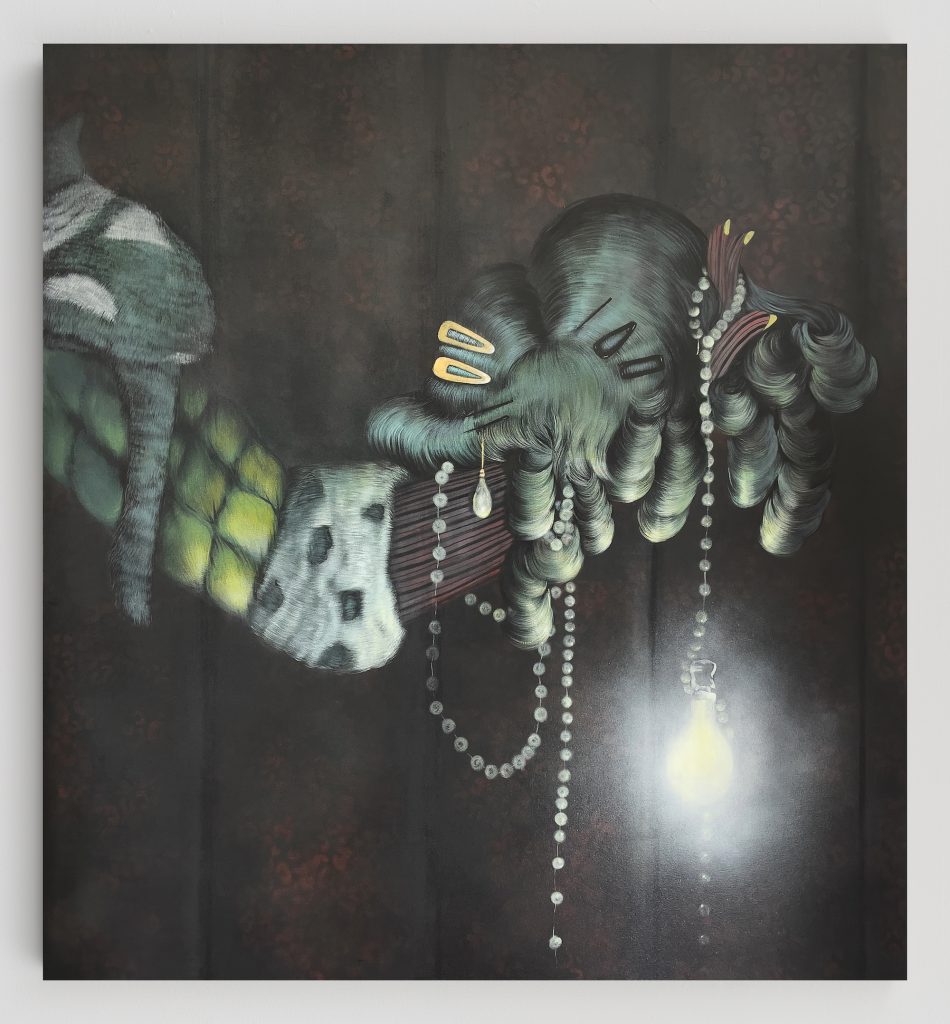

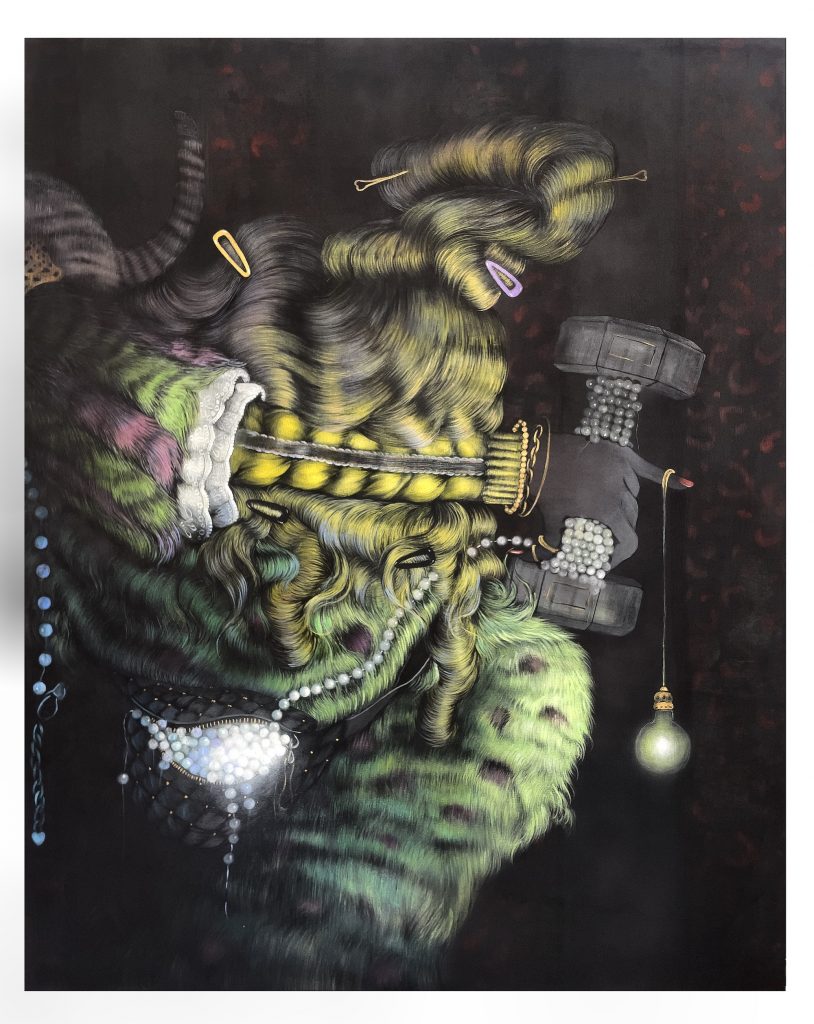

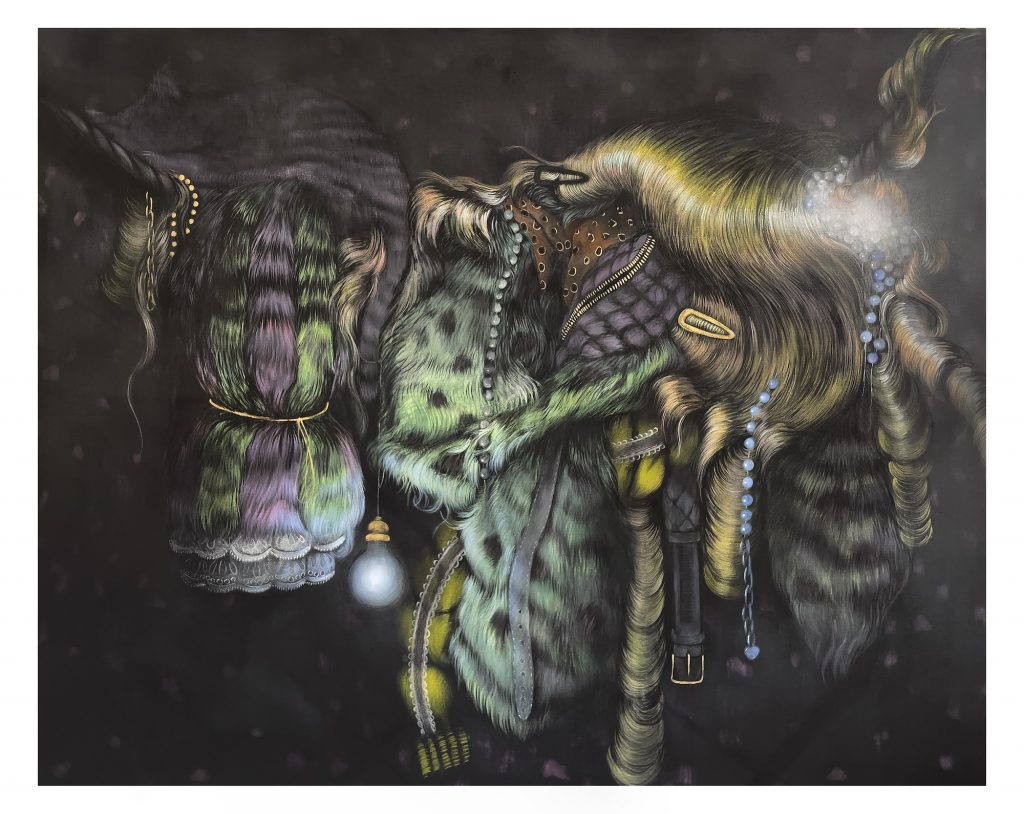

When I visit Scaccia in his studio in Long Island City one afternoon, paintings in progress lined the walls, creating a theatrical tableau. His nocturnal scenes depict rooms covered in wallpaper and seem to glow eerily from within. Hair – wigs or fur, one cannot quite discern them – act as the particular protagonists of these images, occupying the canvases with their eerie, unnatural hues of acid yellow, bluish greens and streaks of purple. Hands and arms, extended in long gestures, cut through hair and fur and offer our only clues of human presence.

“The fairy tale is very beautiful. I think about this tension between the very ugly animal skin and the depiction of the beautiful white hands of the princess,” Scaccia explained of her paintings. “The beauty exists underneath and the disguise itself is what helps her find her identity. Women always try to escape the animal form in mythology as a kind of protection”

This new series is being prepared for a debut next spring at Art Brussels with the Maruani Mercier gallery. Scaccia’s evocative paintings, which dance between the grotesque and the glamorous, the figurative and the surreal, have captured the attention of gallery owners and collectors over the past three years. Earlier this spring, she presented new works at NADA with the JDJ Gallery in New York, following her first solo exhibition with the gallery, “With Their Striking Features”, in 2022. She has also been included in “Death Of Beauty,” a group show at the Sargent’s Daughters location in Los Angeles earlier this year.

The paintings occupy a single, ornate, feminine and decidedly dark space.

“I’m so personally fascinated by her line of inquiry into gender in her work and how her compositions dance precariously on the delicate line between femininity and monstrosity,” JDJ’s Jayne Drost told me. “I believe Bea creates worlds in her paintings, and while those worlds feel unique, they are rooted in myths, stories, stereotypes, and cultural traditions that date back centuries, but still feel ancient. news.”

Bea Scaccia, yellow vermeer (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

Others accepted. This winter, Scaccia will be in residence with the Marea Art Projectt in Praiano, along Italy’s Amalfi Coast. She was personally invited by Carol LeWitt, collector and wife of the late artist Sol LeWitt, whose ancestral home Casa L’Orto is the residence, after LeWitt saw her work in a social media post shared by the Katonah Museum of Art. There, Scaccia plans to develop new works centered on local Italian myths and tales. Previously, the artist willingly spent long days in the studio, often arriving at dawn and working for 10 or even 12 hours straight. She feels there is no time to lose.

Scaccia grew up in the small town of Veroli, then studied and taught at the Academy of Arts in Rome for much of her adult life. She came to New York for a residency about ten years ago and decided she had to pursue a career here. “Even though I’m Italian, I felt more welcome here,” she says. “Rome can be very closed, especially for women.”

Taking jobs ranging from gig work to babysitting in New York, Scaccia eventually found work in the studio of Jeff Koons and, later, Marilyn Minter. In these roles, she was coveted for both her hyper-realistic ability and her speed. At the same time, she was wading through her own creative development.

“I spent years copying other artists and didn’t know how to paint myself. I was pposing with Photoshop and building references, but I was always disappointed. I even went to therapy once – just one session because it was too expensive – to figure out why I couldn’t paint. Maybe it was 2018,” she explained. “One day I decided that maybe I didn’t need the reference imagery anymore. That’s what was holding me back. I did not want to be realistic: the reality did not satisfy me.

Bea Scaccia, Evaluate your options (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

Now its process is much more intuitive. Scaccia sometimes draws at home in bed, cfiguring things out in a way that she finds intriguing. Sometimes she starts with no sketches at all. She begins her canvases by usually airbrushing certain elements and patterns into her backgrounds, then paints in acrylics, adding and subtracting elements and changing tones. She works on several canvases at once, moving on to the next piece when the process starts to feel forced. “I find solutions when I move on,” she explained.

If his paintings are not realistic, they are richly referential. His studio is a treasure trove of books on art history, fairy tales and myths. Clips of colorful wigs and feathers are pinned here and there to the studio walls.

“Come see this,” she told me, opening a plastic bag. The bag was filled with tangles and tangles of costume jewelry. “I was looking online for some really over the top and disturbing jewelry and this came up. You can basically buying junk jewelry from people’s drawers,” Scaccia said, holding the mass of cheap jewelry like an amulet. “It was only $10.”

Bea Scaccia, are we going out (2023). Courtesy of the artist

Jewels will be put to good use. Ornaments abound in his canvases. Pearls are a recurring motif, appearing in clusters so opulent they become distressing.

“The pearls remind Renaissance, of course,” Scaccia said. “A symbol of beauty in a classical composition almost becomes an infestation, something that cannot be got rid of. I operate in an excess of everything. I’ll add too many beads, too many handbags, too many clips.

The hair, likewise, becomes exaggerated, an identity performance, a warning. “I have doubts every day that we know who we are,” Scaccia reflected. “But the surface is actually our deep depth. The way we present ourselves gives us a sense of stability about ourselves; performance gives us our idea of continuity. If you think about Renaissance hairstyles – they were perfect – and these hairstyles looked like they could stay that way forever. But with that sense of beauty, you also realize how dirty and heavy it must have been too.

The theater is never far away. In these more recent works, isolated light bulbs hang overhead, an element reminiscent of the work of Francis Bacon and Philip Guston, but also a theater set. We can imagine actors backstage in a fitting room putting on and taking off clothes in these paintings. A vestige of clothing that I recognize in his paintings—a lime-yellow frock coat with ermine fur trim—is a reimagining of a coat in which Vermeer costumed many of his sitters.

“Even though I’m Italian and the Renaissance is everywhere, I’ve always loved northern painters, especially Vermeer,” Scaccia said, “it’s the attention to detail and the artifice that I love [about] Flemish artists.

For Scaccia, these elements of staging and costumes serve a transformative function. She noted the work of Domenico Gnogli and artist and writer Alberto Savinio as influences in her understanding of metamorphosis. “Right now, we live in a baroque period full of turmoil and scientific discovery,” she said. “We have lost everything that was the animal part of us and so we wear it as the protection we need.”

When I asked her where her interests would take her next, Scaccia told me she was evolving. “I think these paintings can get bigger,” she said. She also tells me that she turns to cats and the proverbial cat ladies, in the great tradition of her compatriot Leonor Fini. I’m starting to notice a cat’s tail here and there in his paintings.

“Reading all these fairy tales, I realized that cats are feminine. And they are feminine in a way, belonging to the cat lady witches who are always alone in the stories we hear. But women do make the cats feel safer,” she said, looking around the studio. “They’re not the scary ones. You never really think about it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.