The coronation of English and then British monarchs was a mutable rite, concocted from a thousand years of grafting religious rituals onto pre-Christian practices. In the center is the codified figure of the sovereign, around which ancient ceremonies and insignia are adapted and embroidered to suit the national atmosphere or the dynastic concerns of a constantly modernizing royal family.

The helmets and swords of Saxon kings are transformed into crowns and scepters, indisputable insignia of royal rank and title, and passed down from generation to generation like batons in a relay race. New ornaments and furnishings are woven into the theatrical performance: thrones and canopies and state carriages in gold ritualized as the emblems of a constitutional monarchy. But the formal imagery of royalty and the workmanship of the king and queen follows the prescriptions of an icon painting, with the adorned halo of crown jewels at the center of each depiction, of Tudor panel painting with Andy Warhol’s serigraphs.

Matthew of Westminster, Coronation of Edward the Confessor, 1042 (around 1300). Ink drawing on parchment. SP. Praise Miscellaneous 572, © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. History and Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

The Coronation of Edward the Confessor, 1042

Edward the Confessor, Saxon king of England and Christian saint, confers holiness on the dynastic monarchy which succeeded him. This image of his coronation in 1042 in Winchester —seat of the kings of West Saxony—was made a century later, with the hindsight of his canonization by the pope. Seated between two bishops, he wears the King Alfred’s [sic] crown “of threads of gold set with precious stones and small bells” (as Oliver Cromwell’s counsel described it six centuries later, when they recast this dangerous symbol of the divine right of kings in ore gold). King Edward had begun to build Westminster Abbey as his tomb and singing chapel: as St Edward it became his sanctuary housing his holy relics and royal vestments, the valuable property of the abbey at keep for all future coronations. Two decades after Cromwell’s destruction of the Confessor’s regalia, Charles II had some of these sacred, powerful objects remade with associative symbolism, and with these Charles III will be crowned.

Anonymous, The coronation portrait of Elizabeth Icirca 1600 (from an original of 1559). National Portrait Gallery. Photography: Prismo Archivo/ Alamy Stock Photo

“Coronation Portrait” of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth Tudor’s coronation was quite superficial. Her few remaining bishops refused to participate, and in 1559 she was crowned by a solitary Bishop of Carlisle, Owen Oglethorpe, wearing the robes borrowed from the Bishop of London, on the date chosen as auspicious by her court astrologer. , Dr. Dee, rather than a holy day. In this icon-shaped coronation portrait, she may be wearing the “personal” crown made for her late sister Queen Mary, encrusted with rubies and pearls and with a single drop of pearl on her forehead, her mantle of richly symbolic gold and silver cloth with dynastic Tudor roses and trimmed with ermine, her hair hanging down in an allusion to virginal purity. According to a viewer, she seemed enormously more cheerful and relaxed once the ceremony was over.

Coronation of James II, 1687, by Francis Sandford

Under the reign of James II, the coronation is transformed into a great staged baroque spectacle. Continuity was essential, with the royal heralds and the Earl Marshal of England adhering to the protocols designed for Charles II, including the use of his regalia and King Edmund’s throne. By order of the King, the genealogist and Lancaster Herald Francis Sandford made these recordings of every stage of the ceremony and even the individual likenesses of the principal actors, published under the title The coronation of James II, in 1687. Every nook and cranny of the abbey is crowded with onlookers, with scaffolding and back-to-back galleries at aisles and crossings and in the churchyard and surrounding streets. Revenue from seats at this great theatrical spectacle went to the Abbey and its staff.

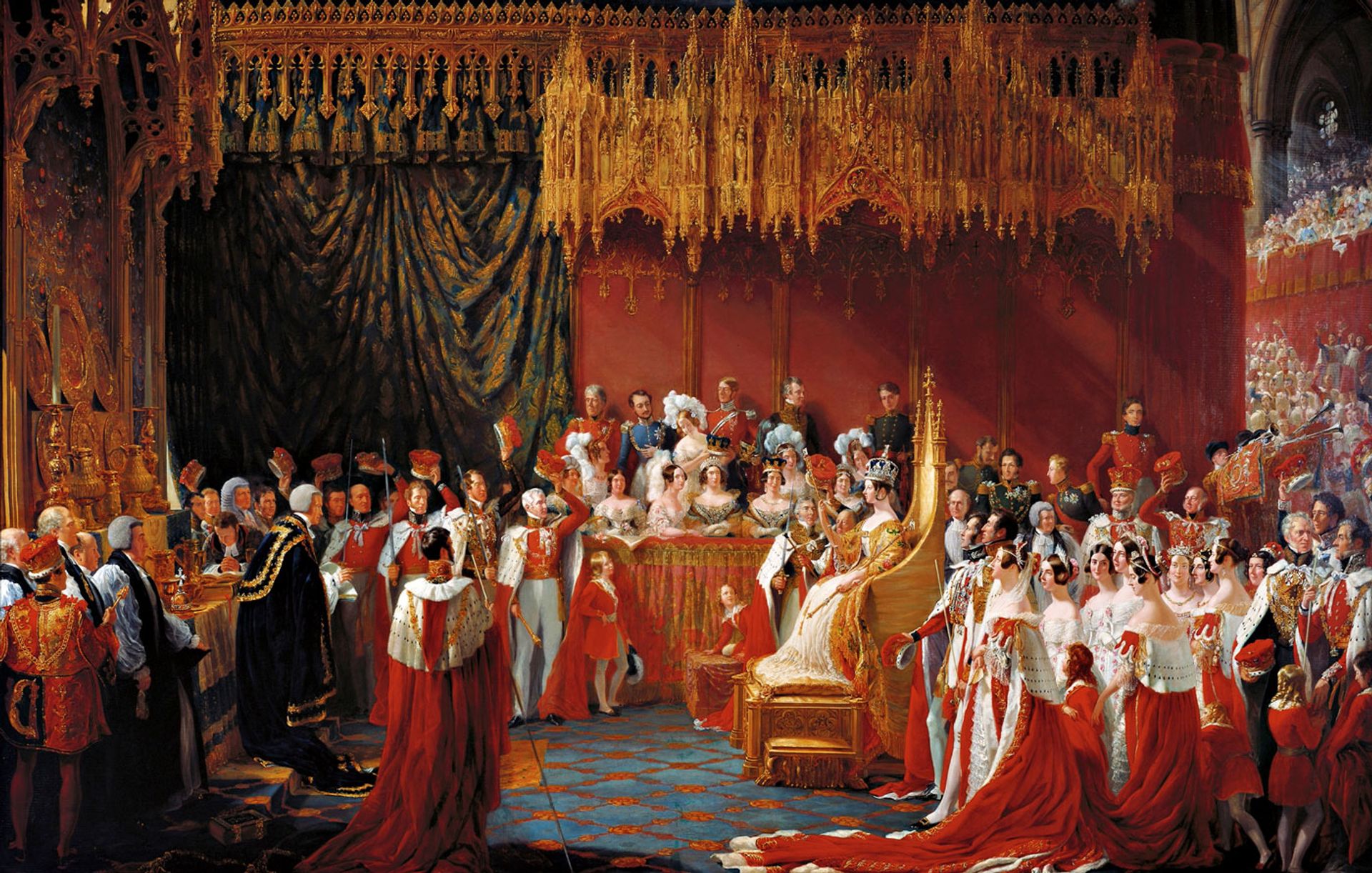

George Hayter, The Coronation of Queen Victoria at Westminster Abbey, June 28, 1838 (1839) Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Coronation of Queen Victoria, 1838, by George Hayter

As well as her drawing master George Hayter’s commissioned depiction of the ceremony, we have Queen Victoria’s own unique visual account of her coronation day. The Queen’s devoted Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, had designed his processional route through the streets of London so that the newly enfranchised populace could feast and fall in love with their 19-year-old Queen. Victoria sketched vignettes of the day in pencil and watercolor, paying particular attention to her own beautifully styled curls and her crowning moment. They are collected in a Souvenirs from the Coronation album in the Royal Collection. Although Melbourne held a rehearsal, the ceremony was chaotic, with the elderly archbishop painfully jamming his coronation ring on the wrong finger. Even so, it brought tears to Melbourne’s eyes.

King Edward VII, seated in the Gold State Coach, drives through the streets of London on his coronation day, 1902 Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

King Edward VII in his coronation coach, 1902

In a reimagining of the state entrance to London used by Charles II, Edward VII traveled in a vast cavalcade designed to showcase imperial power. In the modern medium of photography we see him traveling to Westminster Abbey in the Gold State Coach, first used at a coronation (for William IV) in 1831, one of the conscious historical anachronisms upon which such a ceremony depends. But the King was still weak from recent illness and surgery and, breaking with precedent, he was crowned by Archbishop Temple with the lighter Imperial State Crown, which he mistakenly placed upside down on the king’s head. Patriotic students from Wye Agricultural College cut a giant wreath from Kent’s chalk hill using the pattern of the Confessor’s Crown from a silver guilder, to mark the event.

George VI Coronation Medal, 1937, by Percy Metcalfe

Following Edward VIII’s abdication crisis, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth were crowned on May 12, 1937, the date originally scheduled for his brother’s coronation. Thousands of people listened to the ceremony on the radio or traveled to London to line the streets and there was huge demand for affordable souvenirs such as this medal issued by the Royal Mint. It was crafted in gold, silver or copper and features modernist yet timelessly reassuring ‘continuity’ profiles of the king and queen, it bearing Charles II’s replica of Edward the Confessor’s crown.

Cecile Beaton, Queen Elizabeth II on her coronation day1953 Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

Queen Elizabeth II, coronation photograph by Cecil Beaton

Posed in her Norman Hartnell-designed robe, Cecil Beaton’s 1953 coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II looks dewy like a movie star, but her regal accessories of robe, scepter, orb and the Imperial State Crown maintain the dynastic tradition. His crowned profile is still ubiquitous on our coins, stamps, and commemorative ceramics and cookie tins, mass-produced by the thousands as keepsakes, as well as miniature die-cast models by Matchbox and Lesney of the jolting Gold State coach. and outdated and his team of horses. who took her to the abbey.