German architect Paul Goesch (1885-1940) was an odd member of a movement that envisioned building a new society on the ruins of World War I. Goesch contributed eclectic and colorful designs to the Gläserne Kette (Crystal or Glass Chain), a circle of like-minded architects in Berlin led by Bruno Taut who exchanged visionary unbuilt designs in the early 1920s.

Goesch had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, and after 1921 spent most of his life in institutions. In 1940 he was assassinated by the Nazis, among the 300,000 killed in the Aktion T4 program which exterminated the mentally ill and disabled. Any patient institutionalized for more than five years can be euthanized.

The current exhibition at the Clark Art Institute (through June 11) in Massachusetts is the first on Goesch outside Germany, and this accompanying publication is the first on the architect in English. It considers Goesch’s warm, alluring colors, his stylistic scope, and, as exhibit curator Robert Wiesenberger has argued, how Goesch expands our sense of what visionary architecture was at that time. Wiesenberger collaborator Raphael Koenig, assistant professor of comparative literature at the University of Toulouse II, examines how Goesch’s tragic biography made him difficult for Germans to categorize and prolonged his obscurity for decades.

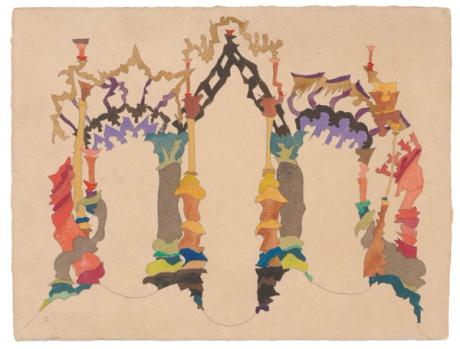

So little is known about Goesch outside of Germany that this wonderfully illustrated little volume will be a revelation. In the years following World War I, Taut called for the “destruction of monuments without artistic value” and the construction of a new order with repurposed materials and groups of structures designed around sparkling, radiant towers, while Hermann Finsterlin, who was also in the Gläserne Kette, defended the construction of forms that resembled waves of energy. Goesch offered different visions, often architectural fragments that were flashes of color arranged in a mixture of styles. A watercolor of three arches, evoking the Middle Ages or an orientalist improvisation, called Sketch for a triumphal gatepresented the Berlin Exhibition of 1920 Ruf zum Bauen (call to build) by activist Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Workers’ Council for Art). In a defeated Germany, everything conceived by a triumphant German was utopian.

Other watercolors by Goesch shine with a warm tawny palette, evoking both Matisse and Klee. He criss-crossed columns with what look like Islamic motifs and sometimes topped them with flowers. The decoration that many of his peers abhorred is everywhere, as are elements from the many cultures whose objects had been pouring into German museums since the 1880s. Wiesenberger calls this work “post-modern proto”.

Along with naïve-minded examples, Portals illustrates sketches of the kind that sent the surrealists to sift through the art of madmen for inspiration. A cartoon around 1920, I will be famous (self-portrait), shows the bespectacled Goesch, similar to Zelig, in a courtyard where every wall of every building bears his name. Later works by Saul Steinberg, Jenny Holzer and others come to mind. Some dense, semi-abstract ink drawings look like roadmaps for Jean Dubuffet.

Coming from a Lutheran family, Goesch converted to Catholicism at the age of 13 and gravitated around the anthroposophy of Rudolf Steiner. Jesus Christ was a frequent subject in the nearly 2,000 works his family managed to save. The Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal, which lent 34 drawings to the exhibition, has 233. Goesch was prolific, so it can be assumed that many have been lost.

In the 1920s, the Prinzhorn collection in Heidelberg, which studied “pathological art” or “patient art”, acquired works but considered Goesch to be an aberrant case because he was an architect by training (at the technical school in Berlin- Charlottenburg). For the architects, he was too fragile a colleague to exercise. In 1934, German doctors forbade him to paint. Four years later, his drawings, seized after their purge from the Kunsthalle Mannheim, are presented in traveling exhibitions of “degenerate art” as a double threat: works of a patient “unworthy to live” and a political enemy. of the Reich.

Yet even after the defeat of the Nazis, Goesch’s drawings were misunderstood. Koenig says Goesch was “pathologized” by psychiatrists looking for evidence of particular mental issues. “Goesch’s presence in post-war psychiatric discourses thus rested on a process of pathologization that involved the erasure of crucial aspects of his work and his identity,” writes Koenig. This presence meant that Goesch was absent from the history of art and architecture – in fact, still locked up in the asylum.

With minimal exposure after 1960, it was not until 1976 that Goesch emerged from this straitjacket, in an exhibition at the Berlinische Galerie. It was the museum’s first exhibition devoted to a single artist. In the United States, four works by Goesch were exhibited along with those of his peers from the 1920s in the 1993-94 exhibition, Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Architectural Fantasy, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A mural Goesch made in 1922 in a Göttingen asylum survives, but a wall and ceiling abstract he co-created in 1921 for a dining room in Taut-designed social housing was destroyed in the destruction. an Allied bombardment.

How the radiant works reproduced in Portals surviving Hitler’s war on the mentally ill and in such good condition is one of the many aspects of Goesch that remain to be explored. For now, it’s the essential book in English about a man who transcended his condition and still paid for it with his life.

• David D’Arcy is corresponding for The arts journal At New York

Robert Wiesenberger and Raphael Koenig, Portals: the visionary architecture of Paul GoeschClark Art Institute, 104pp, 46 color illustrations, $25.00/£20 (pb), published in the US April 4, UK June 13