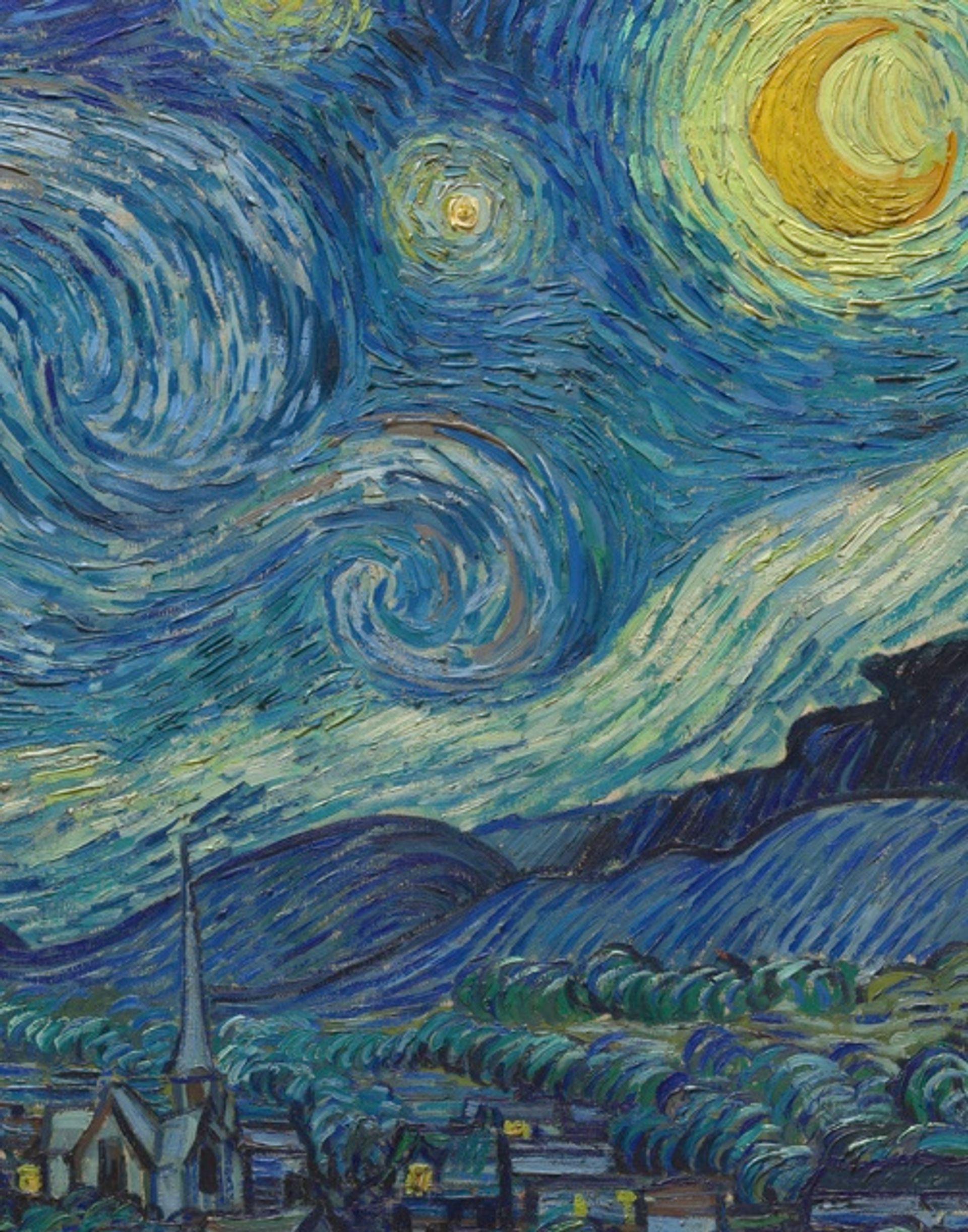

The most popular painting in the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York on Van Gogh’s Cypresses (until August 27) is unquestionably Starry Night. It is on loan from the Museum of Modern Art, where it is normally a major attraction, surrounded by admirers.

An unusual moment of calm during an exclusive preview of Van Gogh’s Cypresses at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Credit: The arts journal

Van Gogh finished Starry Night in mid-June 1889, a month after his arrival at the asylum in the suburbs of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. But even with such famous paintings, there is always more to discover, which is why we present you with ten surprises.

Moonshine in the “wrong” direction

Van Gogh detail Starry Night (June 1889)

Credit: Museum of Modern Art, New York

Van Gogh illuminated the left side of the church in the landscape, while the main source of light should come from the crescent moon on the right. Using artistic license, he shone a bright light on this nighttime scene from the stars. It was a painting of his imagination.

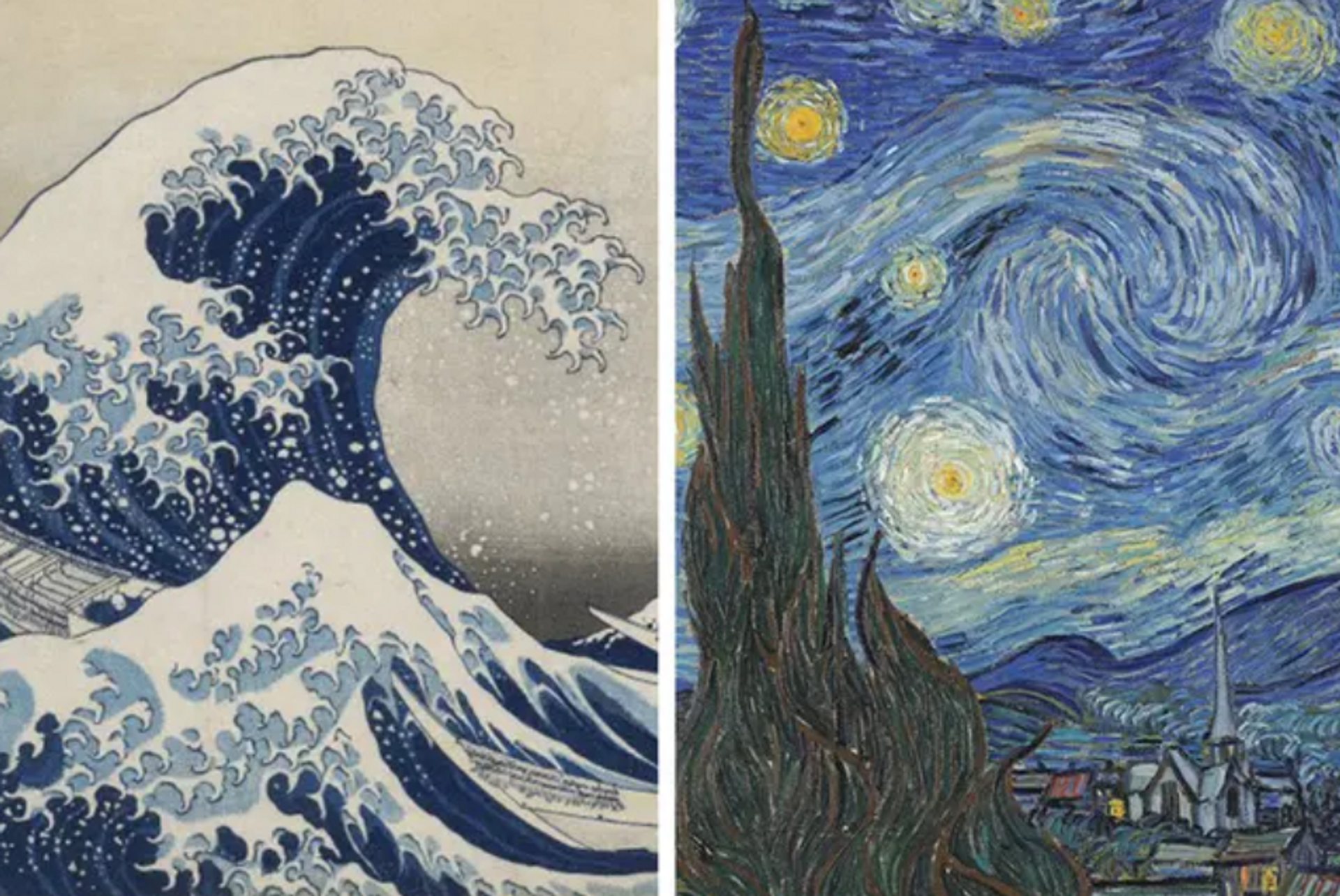

A swirling sky inspired by Hokusai

Details of Katsushika Hokusai The big wave (circa 1831) and Starry Night (June 1889)

Credit for Starry Night: Museum of Modern Art, New York

Vincent was a great admirer of The big wave (circa 1831). He wrote to his brother Theo a few months before painting Starry Night: the “waves of Hokusai are claws, the boat is caught in it, it feels”. In the Hokusai print, the wave towers over the volcanic peak of Mount Fuji, while in Van Gogh’s painting, the swirling mass in the sky rushes towards the gentler slopes of the Alpilles, the hills that lie just behind the asylum where he was then staying. These two compositions in blue share a remarkable dynamism. Van Gogh may well have been loosely inspired by The powerful image of Hokusai.

Six tubes of white paint

A week before starting Starry Night Vincent received fresh art supplies from Theo in Paris, including two large tubes of cobalt blue, one from ultramarine, and six of white paint. While he certainly didn’t exhaust it all on this particular image, he used paint with almost inordinate abandon, creating the thick impasto surface of his star-filled sky. The package containing Theo’s supplies also included “tobacco and chocolate”.

A working weekend

Van Gogh worked incredibly quickly, probably painting Starry Night the weekend of June 15-16. He had been thinking about a “star” painting for months and would have frequently observed the Milky Way and other stars from his bedroom window, so he was ready when he picked up his brushes. It was not painted at night, but in another cell of the monastery which had become an asylum and which served as his studio. Once the canvas is on its easel, progress is rapid. In a painting in his studio one can see what is probably Starry Night: the largest picture hanging on the right side of the wall.

by Van Gogh Window in the Studio (September–October 1889)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

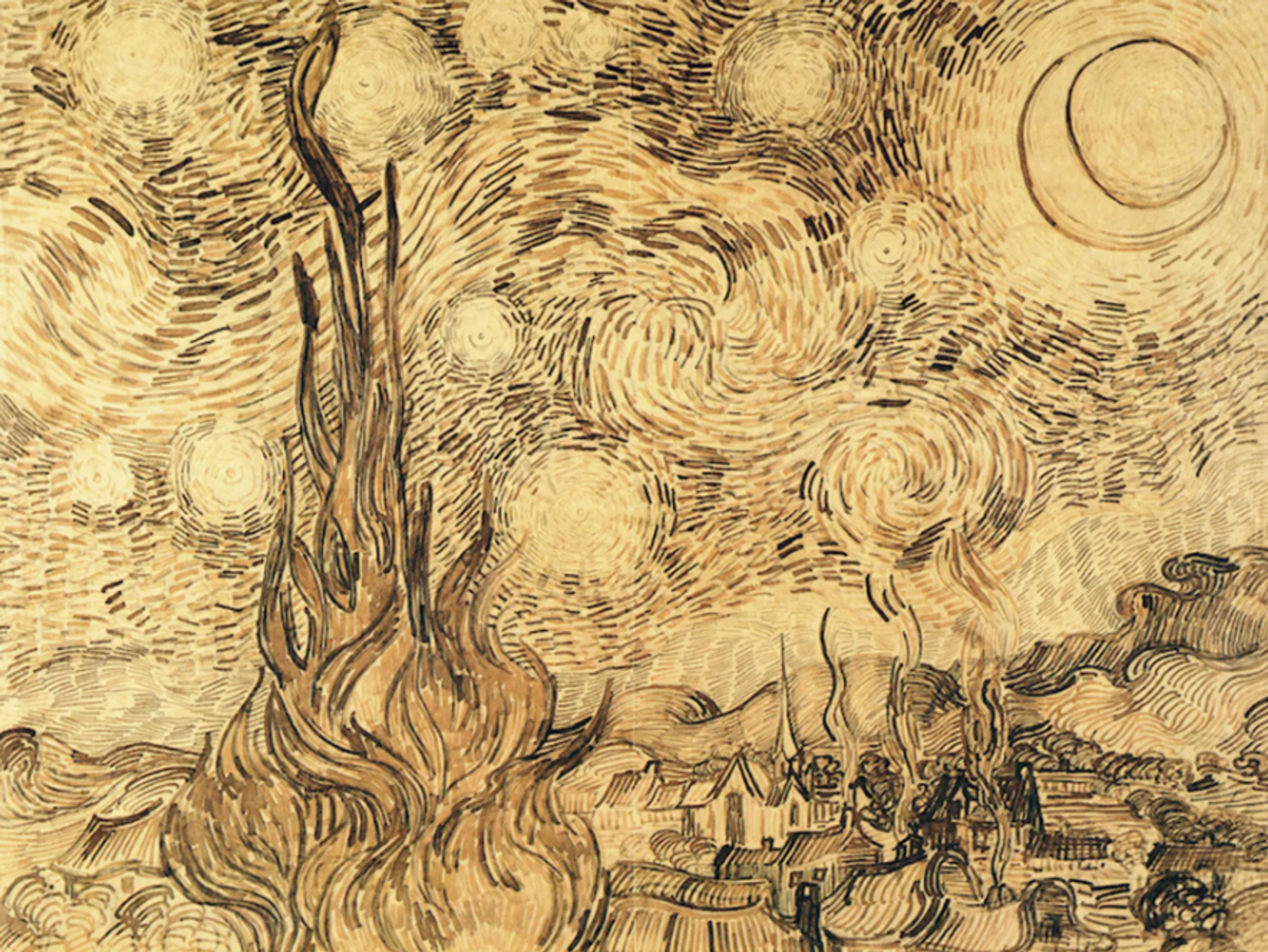

The drawing you’ve probably never seen

Van Gogh’s drawing of Starry Night (June 1889)

Credit: Bremen Kunsthalle (but now held in Moscow)

Van Gogh produced drawn copies of around ten paintings in the summer of 1889, including Starry Night. This drawing was donated to the Kunsthalle Bremen in 1918, but was lost during the WWII chaos. It was looted from a German castle, where it had been sent to safety, by a Red Army officer who brought it back to the Soviet Union on a tractor. In 1992, I was the first foreigner to see the drawing, which was then in the secret storage of the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. The Russian government refused to return the looted Van Gogh and it was transferred to a Ministry of Culture store in Moscow, where it is.

Was Starry Night a failure?

Vincent had ambivalent feelings about the painting, initially calling it a “study”, although a few weeks later he hung it in his studio. realizing that Starry Night marked something of a departure from his recent work, Vincent warned Theo that the composition might seem like an “overkill” – not a realistic landscape. When Theo received it in Paris, he responded with a few carefully chosen words of mild criticism, commenting that “the search for style takes away the true feeling of things”. In November 1889, Vincent wrote to his artist friend Emile Bernard that the painting represented a “setback”, adding that “once again I take the liberty of making stars that are too big”.

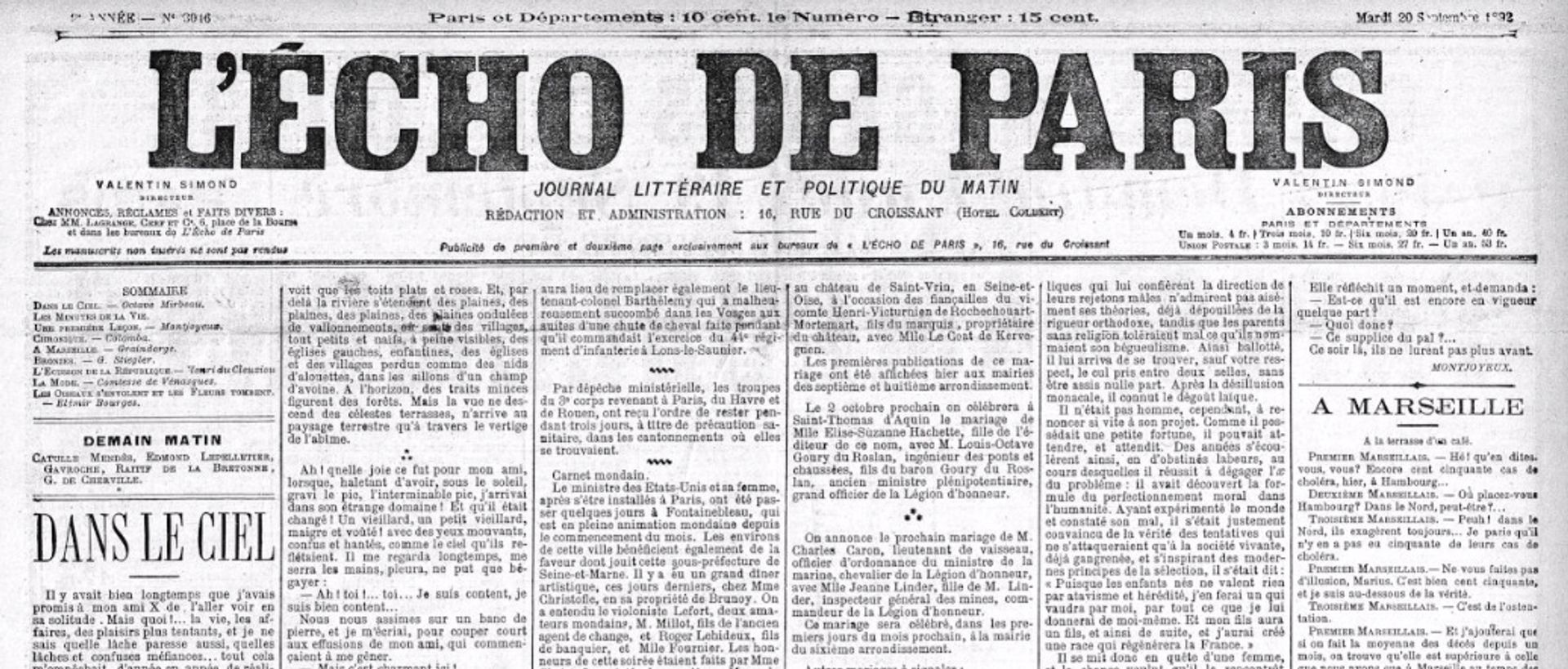

The first novel inspired by Van Gogh

First episode of Octave Mirbeau In the sky (In the sky), The Echo of ParisSeptember 20, 1892

Octave Mirbeau, writer and critic, saw Starry Night in 1891, two years after Van Gogh’s suicide, writing of “the admirable madness of the heavens where the drunken stars turn and stagger, stretching and stretching in tails of seedy comets”. His 1892 novel In the sky (In the sky), published in The Echo of Paris, revolves around a tragic artist who paints trees “with twisted branches” and landscapes “under swirling stars”. It ends with a gruesome scene in which the performer saws off his right hand with a hacksaw and then dies. The main theme of the novel is the connection between genius and madness.

Hanging in a veranda

A woman from Rotterdam, Georgette van Stolk, bought Starry Night in 1907 from Theo’s widow, Jo Bonger. Van Stolk kept the painting in his veranda, but fortunately it seems to have escaped damage from sunlight or humidity. After a few years, she hung a protective curtain in front of her on hot summer days.

MoMA had Starry Night in the blink of an eye

Ad in Bulletin of the Museum of Modern ArtNovember 1941

Credit: Museum of Modern Art, New York

In 1941, Starry Night was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art. It is often assumed that it was purchased, but it was in fact an exchange. Starry Night was traded by the art dealer Paul Rosenberg for three paintings bequeathed by Lillie Bliss: Cézanne Portrait of Victor Choquet in an armchair (now Columbus Museum of Art), his Fruit and Wine (Pola Museum of Art, Kanagawa) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec May Belfort in Pink (Cleveland Museum of Art). In return, Rosenberg offered Starry nightwhich he had purchased from Stolk, and it became the first Van Gogh to be acquired by a New York museum.

Van Gogh never called it “Starry Night

Vincent himself never referred to the painting as a “starry night”, variously giving it the less evocative descriptions of “starry sky”, “nocturnal study”, and “night effect”. Theo called it “the moonlit village”, perhaps viewing it more as a landscape than a representation of the sky. After the artist’s death, he was often known as “The Stars”. It was not until it appeared in an exhibition in Rotterdam in 1927 that the painting was given the more lyrical title “Starry Night (Sternennacht in Dutch).

Other Van Gogh short stories:

Taschen’s latest mega-tome, The history of press graphics 1819-1921 by Alexander Roob, includes a 60-page section on Van Gogh’s ‘Bible for Artists’. This reproduces images he admired in journals such as The Illustrated London News, The graphic And Harper’s Weekly. These illustrations played a key role in the inspiring development of Van Gogh’s own work in the early years when he began his career. He considered his collection of prints “a kind of Bible for an artist”.

All Adventures with Van Gogh blog posts are © Martin Bailey