Carrie Mae Weems is widely recognized as one of the most influential American artists working today. She is best known as a photographer, but her complex work encompasses video, text, installation, sound and digital images and has challenged representations of race, gender and class for more than four decades. decades. Laurie Simmons, Mickalene Thomas, Shirin Neshat, Catherine Opie and Hank Willis Thomas are among the large community of artists who recognize the impact of this personality on their work.

In 2014, Weems was the first African-American woman to receive a solo exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and in 2021 she took over the Park Avenue Armory with a giant film installation and a performance-based show focused on on the history of violence in the United States. This epic work has been reconfigured into a seven-chapter panoramic film that is the culmination of Carrie Mae Weems’ new investigation at the Barbican in London, her first solo exhibition at a British institution and the largest presentation of her work in Europe.

The Art Newspaper: You were initially trained in dance, but it was when you were given a camera for your 20th birthday that you decided to take up photography seriously. What attracted you to photography?

Carrie Mae Weems: I didn’t really know I wanted to be a photographer until my boyfriend gave me the camera. And almost immediately everything literally fell into place. I had never thought of taking pictures before but from the first picture I took I knew it would become my tool and my path and that I was going to go all the way.

by Carrie Mae Weems Untitled (Woman and girl with makeup) KItch Table Series (1990) © Carrie Mae Weems; Courtesy of the artist; Jack Shainman Gallery; New York / Barbara Thumm Gallery; Berlin

In your two years 1981-82 Family photos and stories and your breakthrough 1990 Kitchen table series, you used a documentary style to portray your family and loved ones – as well as yourself – but the goal was absolutely not to document. Why did you take this approach?

Although I was very interested in the documentary format, I had ethical concerns about photographing people without their knowledge and/or consent. So it was out of my concern and discomfort with the documentary format that I started photographing myself and using my own body and my own family as a conceptual framework to deal with larger ideas, but by doing it in a way that I actually had control over. My family and I were available material for the exploration of ideas, concerns and assumptions about the body, about politics and about the family – and in this case the Black family. At the time, I was not so focused on the notion of performance. The idea of acting a certain way in the presence of the camera didn’t come to me until much later, when I looked at my photographs and had a better understanding of what I was actually doing.

But for a long time still, viewers persisted in reading these works solely as autobiographical.

This inability to understand the work and this refusal to consider the work beyond what seemed to be “immediately present” has a lot to do with the times. Insofar as the work was in some respects adopted, it was also rejected. It was not considered concept art. It was easier to just talk about race than to talk about the more complex issues that were really explored through the work itself. There had never been anything quite like it, and viewers and writers had no frame of reference to unpack a blackbody beyond itself. The only thing that was even vaguely similar was Cindy Sherman’s [Untitled] Movie stills, but for many years no one wrote about us in the same breath. Until very recently, there has been a refusal to engage with the work more deeply, more intellectually, more compassionately, and to position it within the framework of post-modernism, which is exactly where it was. positioned.

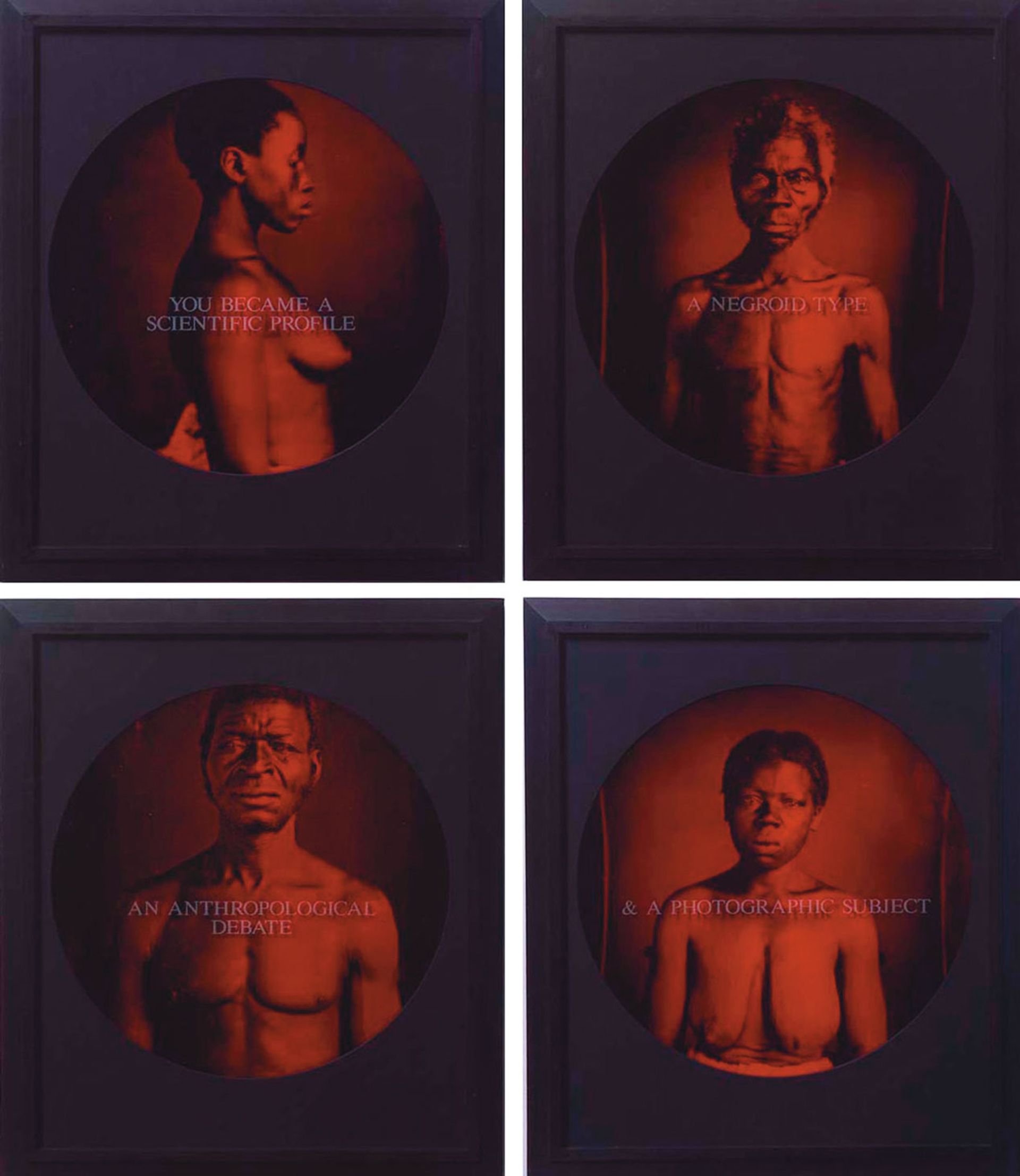

Four works by Weems From here I saw what happened and I cried (1995-96) series © Carrie Mae Weems; Courtesy of the artist; Jack Shainman Gallery; New York / Barbara Thumm Gallery; Berlin

Another series that has also been denied a nuanced reading is From here I saw what happened and I cried (1995-96) in which you rephotographed 33 often poignant 19th and 20th century photographs of enslaved Africans and African Americans and presented them in a circular format under sandblasted glass with texts you had written .

I am not a historian, but I am deeply interested in the history of how images are made, presented and constructed, and I try to reach their deep meaning. So this work can be looked at in terms of American photography, in terms of African American representation, and also in terms of contemporary American photography and white photographers and their assumptions around blackness. […] There are so many ways to unbox it. But for a long time the levels of the work, its structure and complexity were simply not taken into account, it was not thought out as fully as possible. Reviewers again turned to the race as a quick and easy way to discuss work without really examining it much further. Now people are just starting to catch up with how the job worked, which is nice to see after all these years.

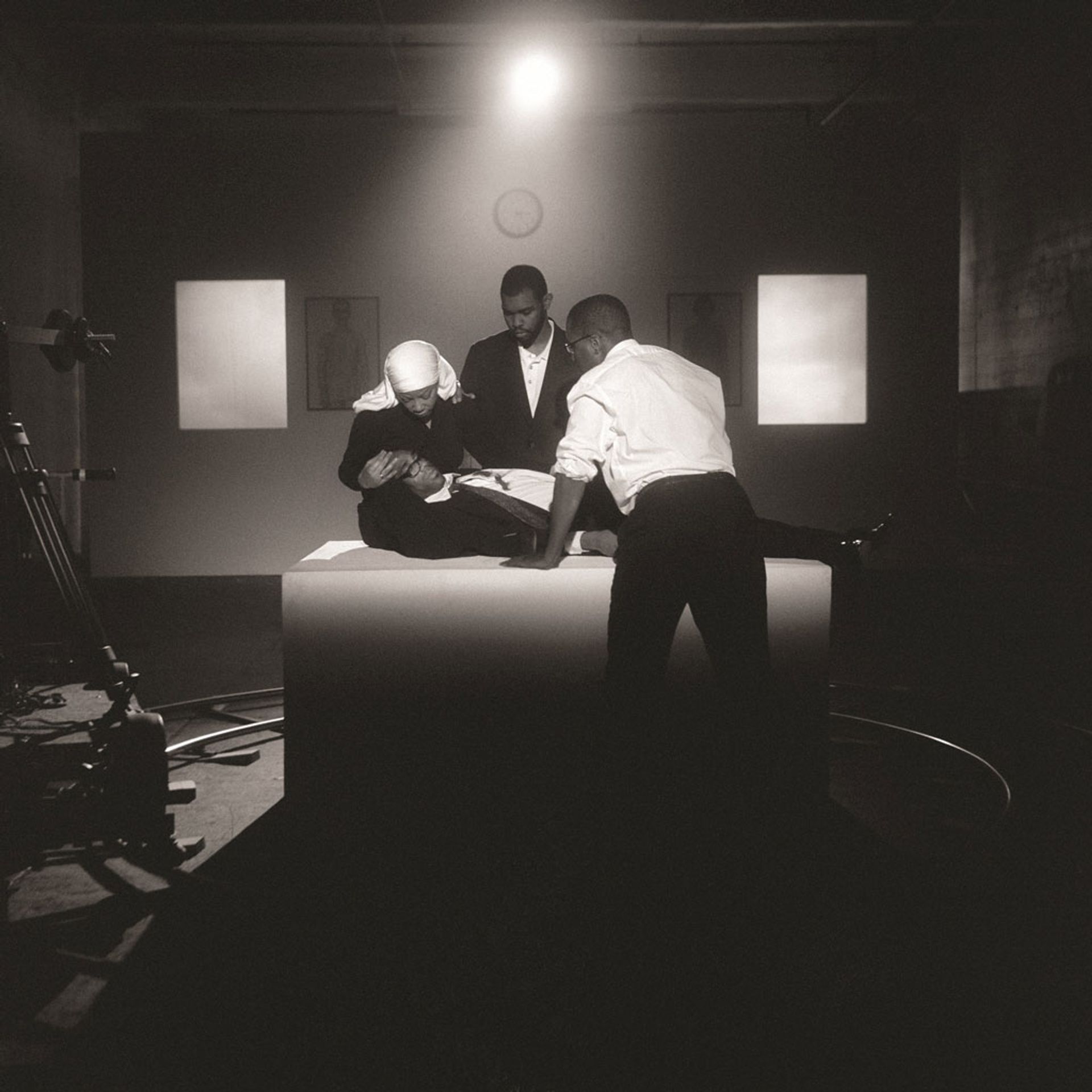

In addition to using documentary footage in your films, you’ve also created your own versions of historic moments in the American civil rights movement and history in general, from the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X to the airdrop from Hiroshima. atomic bomb. Why did you choose to do these reconstructions?

The decision to build certain things refers to my ethical concern of what right do I have to appropriate the work of others? So I thought how wonderful it would be to use a group of people with myself to reenact those moments and tease them in a very different way by presenting them as a performance where the whole image building – the track, the lights, the camera – is also clear to the viewer. Through this understanding that all photographs are constructed, you are invited into a certain type of story and a certain type of complexity that you wouldn’t ordinarily get if I simply appropriated existing images. I challenged myself to move beyond appropriation to construct my own constructed memory and to ask my students, colleagues and friends, to participate with me in constructing things that have been historically significant to us and who made us who we are. .

by Weems The Assassination of Medgar, Malcolm and Martin from Building History (2008) © Carrie Mae Weems Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York / Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin

Your images are also meticulously composed and can be beautifully alluring. What is the place of beauty in your work?

I think it’s partly a way of leading the audience to complicated subjects. It’s disarming. It allows us to get closer to memories, ideas from which, most often, we would turn away except that the image is convincing in itself. Also I am an image maker, I like beautiful things!

You’ve also often taken your art out into the world to confront injustice, most recently with the Resist Covid/Take 6! public health campaign, designed to draw attention to the impact of Covid-19 on black populations, Latinos and Native Americans. Do you consider yourself an activist as well as an artist?

I’m a politically minded person and I think it’s important to be able to step out of the museum and gallery to bring important ideas and visual material directly into diverse communities. I don’t know if I’m an activist, I think I’m a deeply concerned artist who is certainly deeply engaged in the historical moment in which I live. I’m impacted, I’m confused, I’m disturbed, I’m angry. And yet, anger has to be controlled: angry art doesn’t normally get me where I need to go. Provocation and investigation are closer to home.

The extensive multidisciplinary installation and performance work of Carrie Mae Weems The shape of things was staged at the Park Avenue Armory in 2021 Photo: Stephanie Berger; © the artist

Biography

Born: 1953 Portland, OR

Lives and works: Syracuse, New York

Formed: 1981 BFA California Institute of the Arts; 1984 MFA University of California, San Diego

Key Shows: 1995 J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu; 2007 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 2014 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York and Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; 2021 Park Avenue Armory; 2022 Württembergischer Kunstverein, Stuttgart

Represented by: Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin

• Carrie Mae Weems: Thoughts for nowBarbican, London, June 22-

September 3