A Paleozoic museum was once in the works for New York’s Central Park. But in a shocking act of vandalism, models and casts of dinosaurs and other ancient animals meant to be displayed there were smashed to pieces and buried in 1871.

Notorious politician William “Boss” Tweed has been blamed in many accounts. The supposed motives were that the evidence for ancient life conflicted with creationism, and moreover, Tweed was unable to obtain bribes on the construction.

But in a new paper released earlier in Mayart historian Victoria Coules and paleontologist Michael J. Benton of the University of Bristol, England, say otherwise.

They say the man responsible was attorney Henry Hilton, who served on both the Central Park Board of Commissioners and the committee to form the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), which sits in Central Park West. to this day and is partly loved for its dinosaur exhibits.

The authors stressed to Artnet News that they would not link the vandalism to the AMNH then or now. The AMNH did not respond to a request for comment on the 1871 crime.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807–1894). 1870 portrait by Henry Ulke (1821–1910), Washington, DC. Source: Collection 803. Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins Scrapbook. Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.

The English natural history artist working on the dinosaur exhibits, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, has won acclaim for his similar work for London’s Crystal Palace. Arriving in New York in 1868, he was immediately invited by the Board of Commissioners of Central Park (BCCP), then in development, to make models for the new institution, which was to be designed by the architects of Central Park, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. While working on the new museum, Hawkins would create very popular and innovative dinosaur exhibits at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

Hawkins was hard at work in a giant Arsenal workshop in Central Park when Boss Tweed took over the park, appointed Hilton treasurer of the parks commission, and canceled the project.

Naturalist Albert S. Bickmore, meanwhile, had recruited such figures as banker JP Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt Sr., into a committee to form a natural history museum. The committee also included Hilton, still a member of the BCCP.

“Thus, as Hawkins began work on the models for his Paleozoic museum and the foundations were dug for the building,” the authors point out, “the BCCP also encouraged the formation of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), with its location on or adjacent to the park.

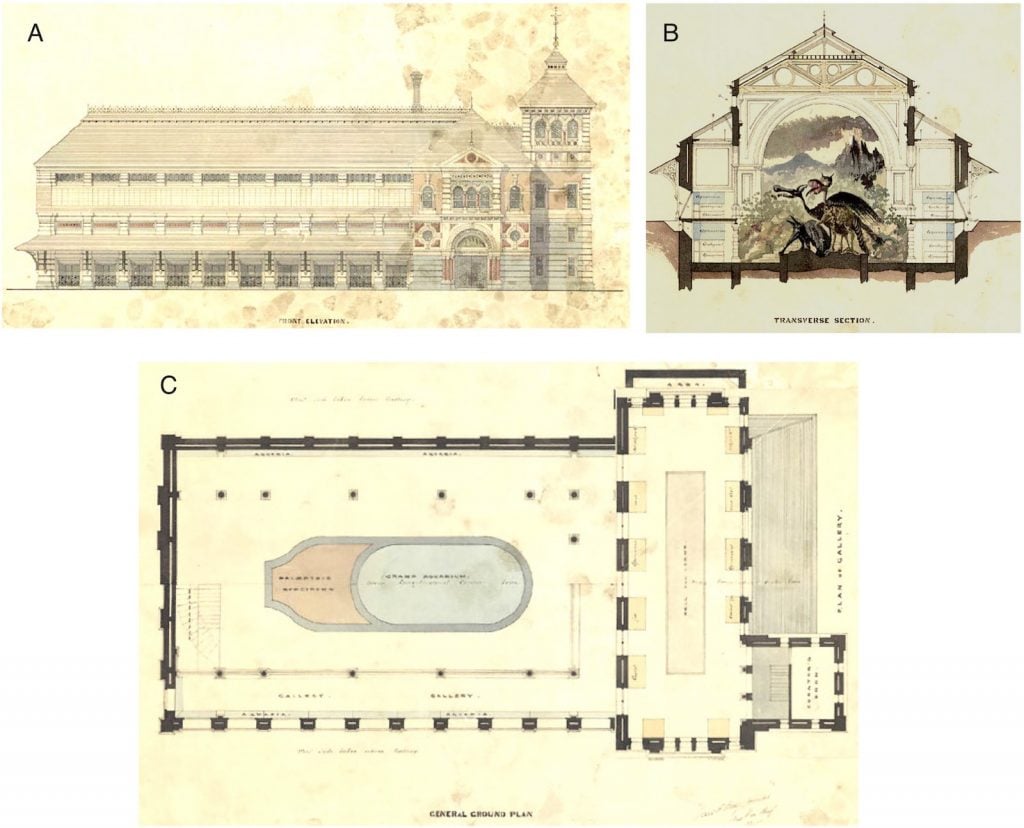

Plans of the Paleozoic Museum, prepared for the Central Park Board of Commissioners by consulting architects Olmsted & Vaux. A: front view; B: cross-section, with fanciful dragon-like dinosaurs; C: plan view.

Announcing the cancellation of the Paleozoic Museum, the BCCP cited the cost ($7.3 million today), which was to be borne by the city. (The AMNH, on the other hand, was funded by philanthropic dollars.)

At a meeting of the BCCP on May 2, 1871, Hilton demanded that the museum’s assets be “disposed of”. The next day, a gang destroyed them all with sledgehammers.

Hawkins quietly moved to New Jersey and worked on paintings of dinosaurs, while sending bills worth $500,000 in today’s currency, which Hilton, as treasurer, rejected. Hawkins never filed charges or complained publicly. He may not have wanted to draw attention to himself: he was a bigamist, say the authors, having abandoned two wives in England.

And why was Hilton’s reaction against Hawkins so extreme? Perhaps even if Hawkins had been allowed to take his plans to another city, they said, Hilton would have seen this as competition.

Moreover, Hilton was unhinged, they said: “Hawkin’s dinosaur destruction in New York was one of many mad deeds in his life; Hilton was not only bad, but also crazy. He “clearly had an odd relationship with art, heritage and artifacts” – they reported that he separately commissioned a prominent bronze sculpture in Central Park and a whale skeleton at the AMNH painted white, damaging both objects. THE New York Times writes: “We are told that he seriously had the idea… to cover the whole park with a coat of white paint.

He, Tweed and the rest of their Tammany Hall crew were eventually exposed as corrupt and ousted from power.

Ironically, the Paleozoic museum probably wouldn’t even have been a competitor to the AMNH (which, in any event, shows much more than dinosaurs), the authors wrote, but looks more like a theme park, displaying more speculative models.

“From today’s perspective,” Coules and Benton concluded, “we can suggest that if the Paleozoic Museum at Hawkins had been completed, it would have appeared obsolete a decade from now.”

More trending stories:

Why Andy Warhol’s “Prince” is actually bad, and the Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith is actually good

The Art Angle podcast: James Murdoch talks about his vision for Art Basel and the future of culture

Sculpture depicting King Tut as a black man sparks international outrage

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay one step ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive breaking news, revealing interviews and incisive reviews that move the conversation forward.